Richard Merrill, the seventh dean of the University of Virginia School of Law, died Thursday of Parkinson’s Disease at age 80.

A mentor to generations of students and professors and an innovator in legal education, Merrill served as dean from 1980 to 1988 and was a member of the UVA faculty for 38 years until his retirement in 2007. Merrill was a nationally recognized expert on administrative, environmental, and food and drug law, and co-authored casebooks and numerous articles on these topics.

During a sabbatical from 1976 to 1978, he served as chief counsel to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, where he received the FDA Commissioner’s Special Citation and the agency’s Award of Merit.

“Dick was a wonderful colleague,” said Dean Risa Goluboff. “There are few people who generate as much consensus about their virtues as Dick. The words 'generous,' 'kind,' 'selfless,' 'thoughtful' and 'engaged' come to everyone’s lips, and so they should. As dean, I am acutely aware that the institution I was lucky to inherit was in many ways the one that Dick built.”

Stanford Law School Dean Elizabeth Magill ’95, who took classes with Merrill and served as his research assistant as a student, then co-authored an administrative law casebook and co-taught classes with him as a professor at UVA Law, said that Merrill’s work as dean “was genuinely visionary — although he never would have said that about himself.”

“He brought UVA Law into an entirely new place from the perspective of financial support from alums — a model followed by every public school that could," she said. He also "aggressively pursued interdisciplinary hires, and modeled for all a commitment to the twin values of a law school — serious commitment to teaching, mentoring and training students and professionals, as well as research and the creation of new knowledge."

He was born on May 20, 1937, in Logan, Utah. Merrill, whose father was a longtime political science professor and top administrator at Utah State University, knew he wanted to be a teacher. He graduated magna cum laude and Phi Beta Kappa from Columbia University in 1959 and attended Oxford University as a Rhodes Scholar, earning a B.A. and an M.A.

Merrill married Elizabeth “Lissa” Merrill in 1961 and moved to New York so he could attend Columbia Law School, where he became editor-in-chief of the Columbia Law Review. Following graduation, Merrill clerked for Judge Carl McGowan on the D.C. Court of Appeals before joining the law firm Covington & Burling in Washington.

After four years in private practice he joined the Law School faculty, in 1969. In his first year, he taught torts and in the following year became a frequent instructor for a yearlong first-year course combining legislation and administrative law, known as “Leg-Ad” to students and faculty at the time. He also started teaching a food and drug law seminar. He taught an Indian Law course for many years.

When a former colleague at Covington & Burling, Peter Hutt, returned to private practice from his role as general counsel of the FDA in 1975, he recommended Merrill as his replacement.

Merrill interviewed with the general counsel of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare, John Rhinelander, a 1961 graduate of the Law School. “My best recollection was that it was a process that had no political dimension at all,” Merrill said in an interview marking his retirement in 2007. Merrill, a Democrat, was hired into a Republican administration.

At age 37, he found himself leading an office of more than 30 lawyers, all but two of whom were younger than he was. The chief counsel’s office brought cases against companies that didn’t comply with FDA statutes, many of which were settled. Merrill also oversaw administrative proceedings, such as hearings on withdrawing drug approval, and dealt with the development and promulgation of regulations, such as food labels and laws governing drugs.

As chief counsel, “I had an opportunity to do or learn to do just about everything a lawyer in a career gets to do — develop policy, draft regulations, appear at hearings, respond to congressional inquiries, draft briefs, argue cases before courts, oversee the litigation activity of maybe a dozen of lawyers that were engaged in suits against companies that were believed to be out of compliance,” he said.

Not long after he returned to the Law School he was tapped to lead it. Reflecting on his accomplishments as dean in 2007 as he was retiring, Merrill said he was proud of the faculty hired during his deanship, including Kenneth Abraham, Pamela Karlan (now at Stanford Law School), Saul Levmore (who became dean at the University of Chicago Law School), Mildred Robinson and Alex Johnson. The school also made dramatic gains in fundraising as state support was shrinking.

Former Dean John C. Jeffries, Jr. said Merrill “was a gentle leader — meticulously observant of the sensibilities of those around him, unfailingly respectful of their views and contributions, and never in such a rush to the right outcome that he stepped on anyone to get there.”

As dean, Merrill created research chairs for faculty, a “brilliant innovation” of endowed positions rotated on three-year terms used to reward teachers and scholars of unusual productivity, Jeffries said.

“If there is an award for ‘genius’ initiatives in the bureaucratic structure of an academic institution, I'd put it on the list,” said Magill, who served as UVA Law’s vice dean before leaving to lead Stanford Law School in 2012.

One of Merrill’s favorite duties as dean was visiting and communicating with alumni. “We have an unusually generous and enthusiastic committed group of graduates,” he said. Merrill said he also enjoyed representing the school to the broader University community.

“I felt like the Law School’s lawyer,” he said.

Merrill inspired many students to go into food and drug law and administrative law, including Stuart Pape ’73, head of FDA practice and a shareholder at the Polsinelli law firm and a former managing partner at Patton Boggs.

“Dick was a wonderful human being — caring and open, always ready with good advice and counsel. He was a prolific and insightful scholar,” Pape said. “I can still remember the first day I met Dick in the fall of 1970 in what was then a required first semester course in legislation, followed by second semester in administrative law. It was in those first-year courses that Dick piqued my interest in administrative/regulatory law, as he did for many others.

“While I have many fond memories of my years as a law student at the University, none is greater than the blessing I received to have known and been taught by Dick Merrill,” he said.

As a scholar, Merrill made his mark with articles on administrative law, such as the regulatory processes involved in food and drug law, and also with work on issues at the forefront of science and law, such as cancer policy, cloning and genetic testing.

"Dick is one of those unique public officials who really was present at the creation of much of our nutritional labeling, and many of the issues that came up in his seminal articles on the architecture of food safety, the architecture of medical products and his work with the Institute of Medicine have been truly remarkable in that FDA and Congress have each paid attention to Dick Merrill's views," said former student James O'Reilly '74 in 2011, during an American Bar Association event where former students and colleagues gathered at the Law School to celebrate Merrill’s work.

"One person can make a big difference in administrative law, and Dick has made a big difference in food labeling and food safety and other regulated product categories," O'Reilly said.

Former student Richard Pierce '72, now an administrative law professor at George Washington University Law School, served as a research assistant while Merrill was writing his textbook on administrative law.

"Everything I've accomplished in my professional life I owe to Dick," Pierce said at the 2011 event, adding that Merrill has positively influenced thousands of lawyers.

"One of Merrill's most convincing teaching methods was his favorite editing tool. You just haven't lived until you've experienced the Merrill red pen," Pierce said.

Magill agreed with the sentiments of these former students and colleagues.

“If we are lucky in our professional lives, we meet someone like Dick Merrill — an accomplished professional, a great leader and a gem of a human being,” she said. “I count myself triply lucky to have known him as a student, colleague and friend. There is no one I admired more, or learned more from, than Dick Merrill.”

Following his deanship, Merrill returned to full-time teaching and research. Later he returned to Covington & Burling as special counsel consulting on food and drug and other regulatory matters.

Merrill was active in numerous professional organizations, including the Institute of Medicine; the Board on Toxicology; the Committee on Science, Technology and Law; and each of the National Academies of Sciences, and he was among the first lawyers invited to join the Academy. He also served on the boards of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation, the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities and Public Policy, the Food and Drug Law Institute, the Southern Environmental Law Center and the Environmental Law Institute, among others.

A memorial service will be held at UVA Law in the coming months. In lieu of flowers, the family requests donations to the UVA Law School Foundation to support the Elizabeth D. and Richard A. Merrill Research Professorship in Law or the American Parkinson Disease Association.

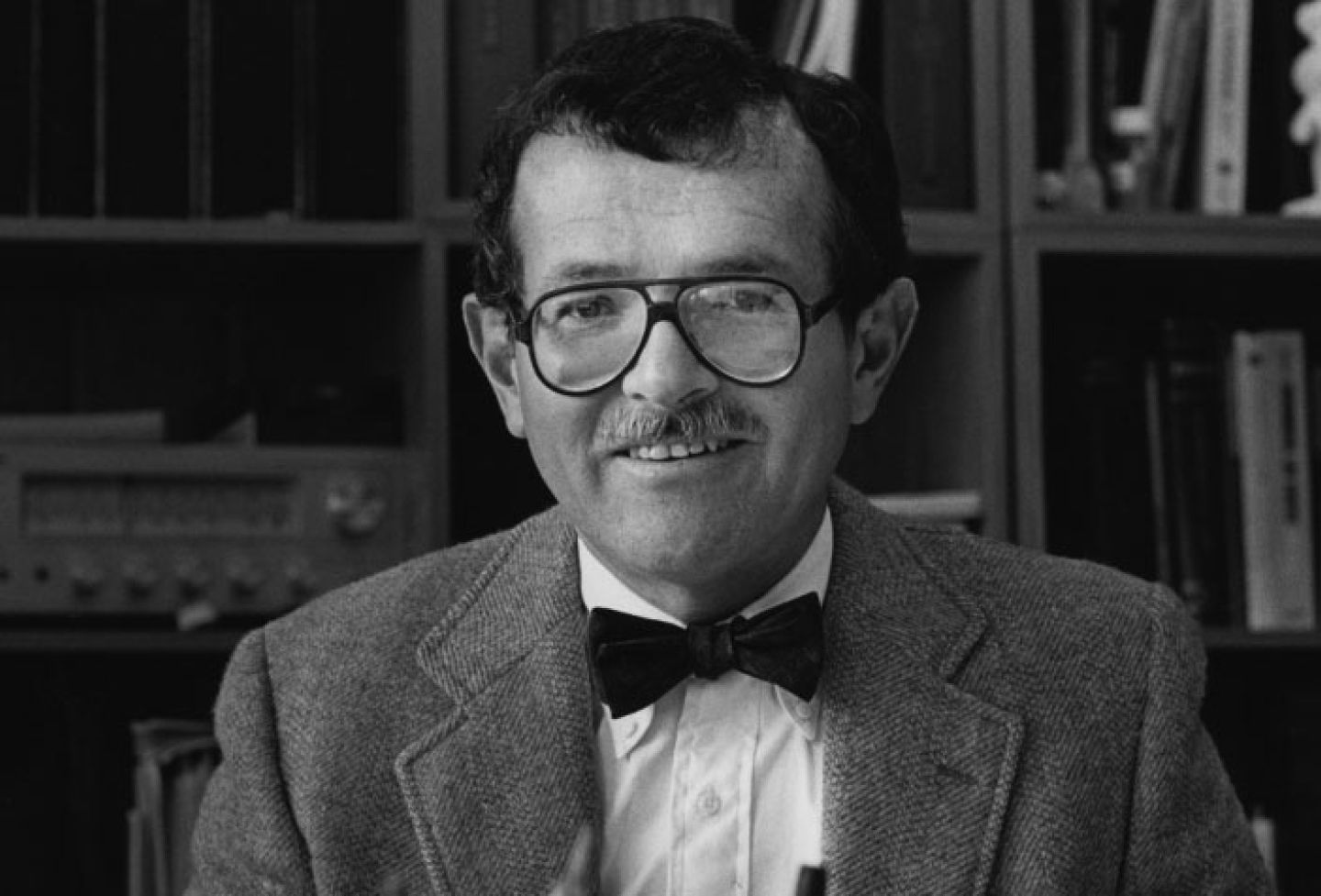

Richard Merrill in his office in 1985.

Richard A. Merrill, then-UVA President Robert O'Neil and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia at an alumni luncheon in Washington, D.C., in October 1989.

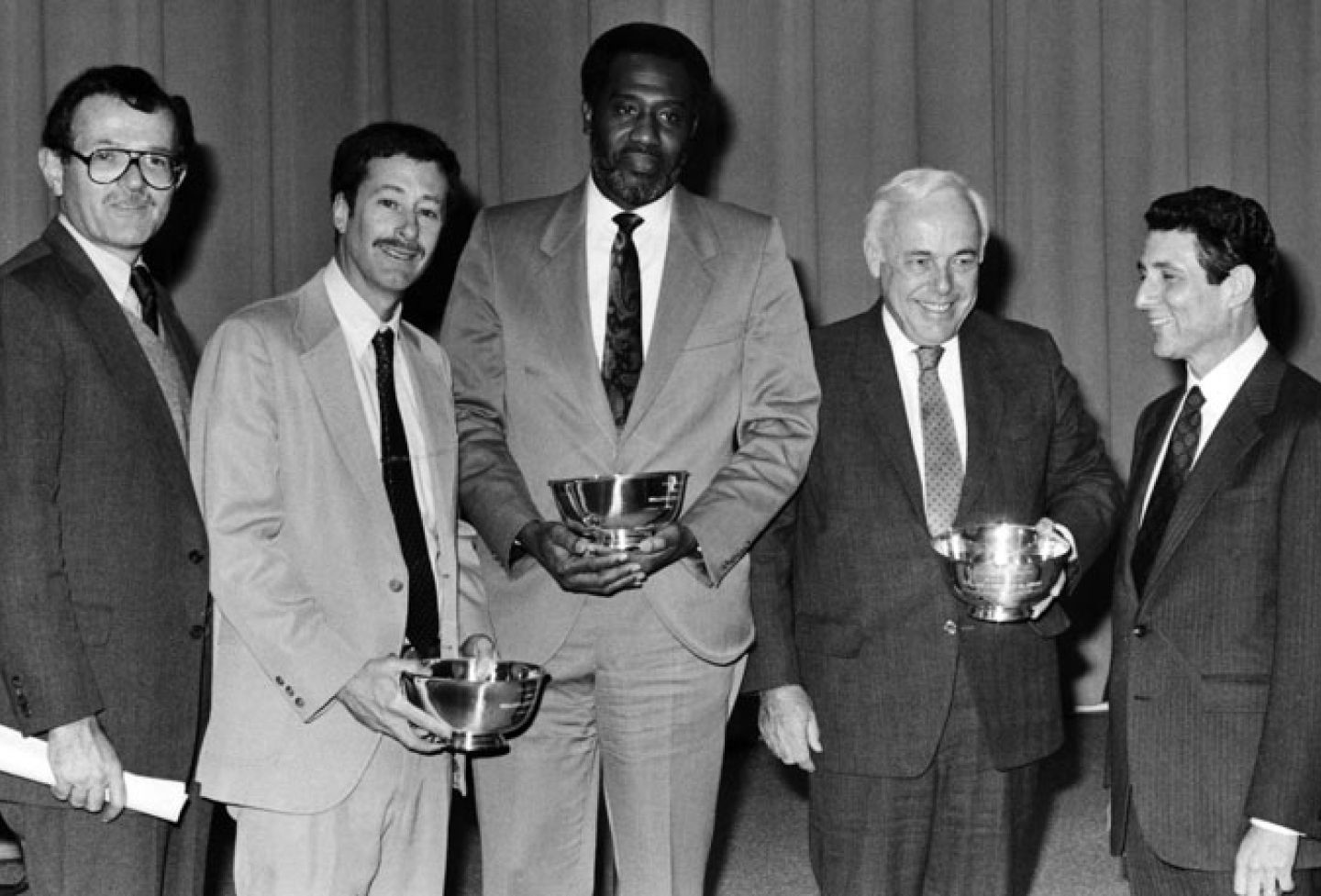

Merrill with then-UVA Law professor Stephen Saltzburg, Charles L. Becton LL.M. '86, James St. Clair and former Federal District Judge Herbert J. Stern of New Jersey during the presentation of the Justice Brennan Awards for teaching at the Trial Advocacy Institute in 1988.

Richard Merrill, Laurence Vogel '60 and Dave Ibbeken '71 (then head of the Law School Foundation) during the testing of a hot air balloon for the Annual Giving Campaign on Oct. 2, 1981.

Merrill teaches a class for the Graduate Judges Program, which conferred LL.M. degrees to judges who completed courses and a thesis.

Merrill with former Dean Emerson Spies; his daughter, Patty '92; his wife, Lissa; and his son, John, at his dean's portrait unveiling.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.