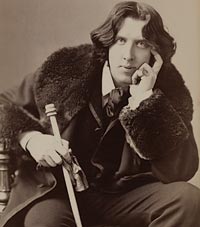

Oscar Wilde

Using Literature to Make Better Lawyers

Denise Forster

FOR YEARS, law professors have woven works of literature—novels, memoirs, short stories, essays—into classes and seminars to tell the stories of law. Using these works, professors and students dissect scenarios not otherwise encountered in traditional legal curricula. A survey of some of the LawSchool’s recent courses follows.

Literature as Gateway

Anne Coughlin says it over and over—there are certain legal spaces where it’s very hard to get information about what’s taking place. To get into those legal spaces, she asserts, “lawyers and law professors almost have to turn to narratives to understand how our system is functioning.”

Coughlin, the O.M. Vicars Professor of Law and Barron F. Black Research Professor, takes her students inside the workings of a jury by reading Trial By Jury, a Princeton historian’s first-person account of serving as jury foreman in a Manhattan trial. Literature can be a place to turn for empirical data, according to Coughlin, who concedes it may be only anecdotal. “We’re bringing into the Law School a text that’s unconventional in the sense that it doesn’t purport to be doctrinal, it doesn’t purport to be written from the perspective of a legal academic or a legal practitioner. But it does fill in the blanks,” she said.

The caption on this 1893

publication reads “A scene

in the court-room before

the acquittal—Lizzie Borden,

the accused, and her

counsel, ex-Governor

Robinson.”

A prior culture’s norms are the blanks that literature can fill. “We have an intuition that women in the 19th century were harmed by extramarital affairs. Well, how do we know that? There aren’t a whole lot of cases on the books. Most of the facts get handled out of court privately and don’t become law cases. To the extent that there are cases on the books about sex, whether it be consensual or rape, the cases don’t tell you very much because judges won’t write about it. It’s indecent. It’s dirty. It’s unmentionable, so we don’t know a whole lot about it. We certainly don’t have the young woman’s perspective. She’s completely lost as a character, so sometimes the best way is to turn back to fiction. You have to be cautious; this is literature and we must be very careful in our generalizations. But for us to understand how they defined rape or how they defined criminal conversation, we need to know more of the facts.”

Coughlin co-taught a course, Trials of the Century: Literary and Legal Representations of Sensational Criminal Trials, with former Law School Professor Jennifer Mnookin, studying essays, trial transcripts, memoirs, short stories, films, and novels, and it worked: the class dazzled professors and students alike.

“We took sensational trials that have become part of our cultural repertoire, our cultural canon. We asked ourselves, what is the great lawyer’s work product? We were interested in the cases that changed legal culture and popular culture, so we used cases that themselves are legends in their own time or have become the basis for movies, novels, and plays.”

The class read portions of transcripts of the Lizzie Borden trial and the lawyers’ arguments, watched a reenactment done by the Stanford Law School, and read a short story about Lizzie. “It was absolutely eye-opening,” says Coughlin, “just riveting in terms of giving you a sense of that hot August day when somebody—we think it was Lizzie Borden, but it was never proved—went and killed Mr. and Mrs. Borden. We were looking for a three-dimensional understanding of that trial in its time and place and its meaning for subsequent generations.”

The class did the same thing with the Oscar Wilde case, looking at the connection between law and literature. Perhaps the most popular playwright on the planet at that time, Wilde brought a criminal libel action based on his lover’s father’s accusation that Wilde was “posing as a sodomite.” For the purposes of the class, “it was just too good to be true,” says Coughlin. “Wilde takes the stand as a playwright who, of course, writes dialogue; some portions of the transcript of the Oscar Wilde trial read like a play. He is so witty and so funny, but then reality sets in. He can’t control it. He’s no longer the playwright. The lawyers are in control and you can suddenly see Wilde’s story starting to disintegrate as his case falls apart, revealing the truth: not only was he in fact posing as a sodomite, he was having sex with many young men.”

The class went on to cover the trial of Socrates, and the Scottsboro boys, and was intrigued by the parallels of the contemporary significance of those trials. “Look at Scopes, the evolution question. It’s right back on the table. Look at Oscar Wilde—gay marriage, gay sex. Right back on the table,” says Coughlin. “We all learned so much—and it was a huge help for practical lawyering. We read a lot of lawyers’ works and studied them together systematically and the ways in which they get represented and readdressed. And we read some of the greatest closing arguments of all time. The words of Clarence Darrow just blow you away. These are students who want to litigate and get up on their feet and they have to learn how to perform. Of course, they’re not all going to be trying the trials of the century, but some of them will. These are brilliant students and I just never saw anything like it.”

Law and Lit in the Classroom

George Rutherglen, John Barbee Minor Distinguished Professor of Law and Edward F. Howrey Research Professor, has taught Seminars in Ethical Values through the years in different settings, working through different genres. He recently co-taught a seminar through the Institute for Practical Ethics with the University’s Taylor Professor of English and American Literature Stephen Cushman.

The class was half law and half English students; the professors worked to establish common themes and techniques of interpretation, crossing multiple boundaries and eliciting comparative discussions of professional ethical commitments while discussing their featured books: A Bend in the River, Atonement, Disgrace, and Emma. As the class progressed, the common themes one finds at the intersection of life and law emerged.

As Rutherglen illustrates, “Implicit in Emma is a discussion of British social class and empire and that comes out much more clearly in A Bend in the River, which is concerned directly with imperialism in Africa. We saw a lot of connections that we could draw from one to another—and all raised ethical issues.

Poster for “The Big Sleep,”

the 1946 film based on the

novel of the same title by

Raymond Chandler.

“Jane Austen is quite concerned with the issue of marriage, which has a lot of political reverberations around feminist issues or issues of gay rights. We talked about Disgrace, which, again, is concerned with Africa and questions of imperialism. It’s easy to teach these seminars once you find the right materials, because almost any work of literature that has any depth at all just raises a number of themes that intersect at a variety of different points with law. Even in books like Emma, which explicitly have only a relatively small legal component, it’s very easy to draw the implications for what our students have to face in their professional lives.”

One of the books Rutherglen most enjoyed reading and teaching for its overlapping connections was Atonement, a cross between a murder mystery and a detective story— something Rutherglen is going to become more familiar with soon. He and Professor Earl Dudley will be examining the detective story and its subgenre of police procedurals, hoping to focus on the strong moral component within. “I think the detective story is a fertile area for examination in law and literature. I don’t read many detective novels, but the ones I’ve read—certainly classic works by Raymond Chandler—have a very strong moral component, where the detective is always someone who’s trying to promote good in a world of evil,” Rutherglen said.

From Hamlet to Homer (Simpson)

Because Professor John Setear’s International Ifs seminar focused on U.S. foreign policy between World War I and World War II, he assigned Philip Roth’s The Plot Against America, an alternative history of the United States that assumes Charles Lindbergh becomes president in 1932 instead of Franklin D. Roosevelt, and then adopts a pro- German foreign policy along with domestic policies that are a trans-Atlantic echo of Nazism.

Setear, the Thomas F. Bergin Professor, chose the book, he says, because he finds Roth to be a skilled author, “but mostly because the book is a very nicely written, literary examination of a what-if possibility set in the period that we study in the course. Also, since the book is somewhat ambiguous about whether the alternative Lindbergh’s policies were first steps toward a very frightening destination or just gestures to keep the Nazis from pressuring the United States, it lets us talk about how hard it is to know during any given event just where things will lead. That is an important point when you’re teaching a course about why the United States, among others, seemed to have its head stuck in the sand about the dangers presented by Germany and Japan during the 1930s.”

In his Contracts class, Setear uses passages from “choice works” of literature—both classics and “literature-lite” to keep things fresh. A few samples:

- When talking about the effect of mental illness on the validity of contracts, the class reads Hamlet’s “what a piece of work is man” speech and asks if he’s depressed enough to get out of contracts he made at the time.

- A passage from The Firm, where the law firm makes employment offer to young Mitch McDeere that is quite specific as to most terms but leaves out the fact that the firm’s clients are definitely crooks. Setear asks if the offer has sufficiently specific terms to be a valid offer (it almost certainly does) and if the failure to disclose the nature of the firm’s clientele is bad enough to invalidate the offer anyway (a tougher call).

- Setear also use some passages from movies based on books, such as The Godfather—the famous offer you “can’t refuse” is actually an offer about signing a release agreement from a recording contract. And the class looks at passages from The Simpsons, which “has enough insights about relationships to stack up favorably against any Russian novel,” for scenes not just about contracts but also about fraud, causation, bad bargaining, and the public’s perception of lawyers.

Setear says he uses these examples “partly for relief from an unremitting parade of cases, and partly to show the ubiquity of contractual concepts. If these ideas pop up in The Godfather or The Simpsons, which most people don’t associate with common-law notions of commercial agreements, then you should expect these ideas to pop up in life more generally. That’s the general idea with literature as a reflection of life—it’s just that here the part of life reflected is the law.”

Race: Just One Defining Factor

As director of the Law School’s Center for the Study of Race and Law, Professor of Law and Justice Thurgood Marshall Research Professor Kim Forde-Mazrui wanted to run a Seminar on Ethical Values devoted to race-related literature. Literary works such as Beloved, Their Eyes Were Watching God, and Cry, the Beloved Country proved to be the provocative fodder Forde-Mazrui had hoped.

Japanese-American internees leaving a

Buddhist church, winter, Manzanar Relocation

Center, California. Photograph by Ansel

Adams.

But race was only one factor Forde-Mazrui wanted students to scrutinize with regard to identity. “One of the things I find useful when studying race is how it compares to other ways we define ourselves. A part of studying race and law is to study gender or sexual orientation issues because they inform each other; the insights we gain from one tell us something about the other.”

An additional aspect his students’ study is the comparison of the experiences of people of different races. His seminar analyzed the novel Snow Falling on Cedars, which is largely about Japanese Americans during the internment and the period that followed. “It has quite a lot to say about law, because it both gives us some insights into what it was like to be Japanese American during World War II, and because a trial is taking place.

“The trial of a Japanese American accused of murdering a white fisherman was run quite fairly. All the actors involved were trying to be conscientious and fair, yet there was this sense it couldn’t be fair. If the defendant is quiet, the whites think, it’s because he’s guilty, not because culturally that’s how he holds himself. There’s a sadness to it.”

An approach to scholarship that emerged in the mid-1980s called Critical Race Theory uses narratives in legal scholarship, according to Forde-Mazrui. “One of the things that critical race theorists argue is that privilege tends to be invisible to the privileged. Privileged people often believe we live in a colorblind meritocracy, so they see affirmative action as wrong because people don’t need a benefit. Everyone should just be treated the same. But critical race theorists contend that this obscures that there are real kinds of economic and political hierarchies connected to race. Literature helps us see that privilege, like in Snow Falling on Cedars, where a Japanese American protagonist was inherently disadvantaged because of the culture. Observing the law on the books and even how it was carried out in practice isn’t telling you the whole story about whether the system as a whole is treating people fairly, at least with respect to race.”

Scholars Tackle Marriage & Family

Associate Professors Risa Goluboff and Richard Schragger co-taught two Seminars in Ethical Values that centered on work, marriage, and family. They used literature to make sense of societal pressure, gender issues and roles, and the ways couples negotiate familial expectations. They brought to the seminar the experiences of their own marriage, parenthood, and work-family balance, as did the students themselves.

Incorporating cultural texts in a broad sense—including popular-culture depictions of families on television sitcoms and in movies—Goluboff and Schragger’s students cover everything from stay-at-home moms to gay men’s experiences with the adoption process. Books such as The Velveteen Father, The Mommy Myth, and The Kid facilitated hours of discussions about things Goluboff says “don’t get talked about very much in law school.”

“I can’t imagine teaching this class without galvanizing books, like I Don’t Know How She Does It. We could not get the students to have just one conversation about it. Some were furious at the book,” says Goluboff, while others found it spoke to them. Although some deemed the novel “Chick Lit” at first glance (the pink cover gave it away), Goluboff and Schragger’s seminar students never failed to choose sides. Either they wholeheartedly supported the working mom turned “Muffia” (Muffia being the tongue-in-cheek name for stay at home mothers who must make everything from scratch and join every child related committee) who tossed aside the high-powered job she loved to stay home with the kids, or they called her a sellout because she excelled at her job, in fact existed for it.

While using a novel to address an issue as complex as parenting roles works for some, the seminar also tackles the issues through such works as The Mommy Myth: The Idealization of Motherhood and How It Has Undermined Women, whose authors assail the ascendancy of what’s been labeled as “new momism,”—the media’s depiction of perfect motherhood—just as many feel women were breaking free of traditional gender roles.

Images courtesy Library of Congress.