Supreme Court Litigation Clinic Wins Big

By Theodore Anderson

Reprinted with permission from Virginia alumni magazine

The Law School played a key role in two decisions handed down by the nation’s high court in its most recent term. Each year, as part of the Supreme Court Litigation Clinic, some of the best third-year students prepare and submit requests to the court to review lower-court rulings. The clinic files up to five certiorari requests—known informally as cert petitions—each court term.

The justices receive about 7,000 cert petitions annually; they accept about 70. If the Supreme Court agrees to hear one of the clinic’s cases, students work on every phase of trial preparation, from conducting research and writing briefs to doing mock examinations of the clinic instructor who will argue before the justices.

In the Court’s most recent term, the clinic litigated two cases: Henderson v. United States and Elonis v. United States. Representing Henderson and Elonis before the justices, members of the clinic won both cases. Since its inception in 2006, the clinic has won eight cases and lost three. In another case, in which there were two issues at stake, it won one ruling and lost the other.

Henderson centered on the right of convicted felons—who are prohibited from possessing firearms—to request that the government transfer their weapons to an independent third party. In May, the court struck down the government’s prohibition on such transfers by a 9-0 vote.

A mix of counsel, professors and students on the steps of the Supreme Court after the Elonis argyment in December. From left, Ronald Levine, Julie Wolf ’15, Abraham Rein, Lide Paterno ’15, John Elwood, Peter Benson ’15, Toby Heytens ’00, Dan Ortiz, Nick Reaves ’15, Trevor Lovell ’15, and Mark Stancil ’99.

Elonis focused on the free-speech rights of a man who had been convicted of making threats against his former wife on Facebook. He claimed that the posts were a form of therapeutic venting rather than a “true threat,” which is the legal standard for conviction. In June, the Supreme Court overturned his conviction by an 8-1 vote, although it left open the definition of a true threat.

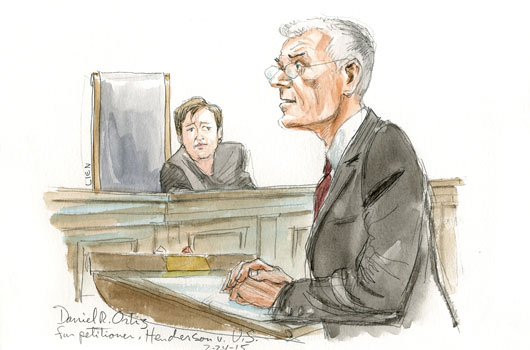

Daniel Ortiz, the Michael J. and Jane R. Horvitz Distinguished Professor of Law, argued the Henderson case before the justices. Ortiz founded the clinic and remains its co-director. “The cases we get tend to be criminal procedure and criminal law cases, where you’re going up against the Office of the U.S. Solicitor General, which is often called the best law firm in the country,” he says. “So we are particularly happy when we win one of these cases.”

In choosing which projects to pursue, the clinic’s instructors and students weigh several factors, including the educational value of a case and its chances of being heard by the court. They selected Henderson and Elonis in part because the lower courts were deeply divided in their rulings. The Supreme Court tends to prefer such cases, which offer the justices an opportunity to settle contentious legal disputes and clarify the law.

“Both cases also asked pretty fundamental questions,” Ortiz says. “Henderson asked what it means to ‘possess’ something, which is critical to property and criminal law, and Elonis asked what mental state was required to convict someone of a ‘word’ crime.”

Taking part in the clinic provides “a sort of capstone experience” for third-year students, Ortiz says. “It takes things they’ve been learning and uses them at what you might think of as the apex of the profession. The level they’re doing it at, and the lawyers they’re doing it against, make the experience a very special one. We have third-year law students going up against some of the most experienced lawyers in the country.”

The number of students in the clinic has ranged from 12 to 17, selected from a pool of 30 to 45 applicants. The clinic has five instructors who advise the students, supervise their work, and argue cases before the court. Students and instructors often work with the litigant’s legal representation in preparing a case, though that relationship varies.

The Supreme Court accepts roughly the same number of cases each year, but the competition to have one accepted is increasing, Ortiz says, as law schools and firms seek the prestige of arguing cases before the court.

The clinic, nearing its 10th anniversary, seems well positioned to remain competitive. Its five instructors all appeared on a 2014 Reuters list of the 75 lawyers who appear most frequently before the court. “A lot of it is trying to understand what the other side is going to say before you say anything,” Ortiz says. “That determines how you actually make the argument. You have to think five moves ahead. That’s not something you would get in many places in law school.”