AP PHOTO/CHARLES DHARAPAK

Health Care: Reform and Rhetoric

by Cullen Couch

Reform and Rhetoric | Constitutional Question| ACA Summary | Accountable Care Organizations | Mental Health Care Reform

For more than two years the country has been hotly debating the availability and cost of health care. Facts and figures continue to be selectively argued, leaving the impression that universal coverage is either a necessary government obligation or an unaffordable social program. If only the policy considerations were so simple.

Health care has been politically divisive for decades. Today, it controls a $2 trillion piece of the economy. Health insurance revenues alone top $500 billion a year. It is an enormously complex issue subject to a host of competing ethical demands. Congress needed several thousand pages to try to get a handle on the health care reform bill passed in 2010 (the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, or the Affordable Care Act), which President Obama signed into law last year. Though critics complain about the Act’s complexity, Michael Graetz ’69, a professor of tax law at Columbia Law School and expert on health care reform, writes that such is the fate of any legislation targeting health care.

|

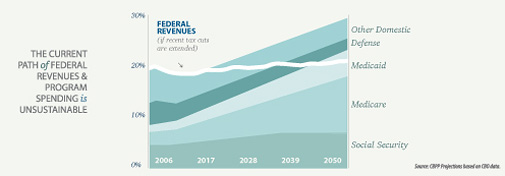

To the scholars and health care professionals who have exhaustively researched the issue, health care reform offers any number of policy choices that would contain costs, improve delivery, and save lives. The solutions they propose involve combinations of government oversight (insurance exchanges, payment review boards, price structures), free market principles (using deductibles, co-pays, Health Savings Accounts), and rational delivery (electronic records, episode payments). They acknowledge four core realities: one, the federal government already accounts for almost half of health care spending in the nation; two, it is virtually impossible to correlate health care expenses with results; three, there will never be a perfect universal health care system, anywhere; and four, without reform of some kind, the nation’s health care system will collapse.

The Health of American Health Care

The United States is indisputably the world leader in lifesaving medical technology and research, especially in cancer care, specialized surgery, and ground-breaking new drug treatments. The U.S. health care industry is also making huge strides in developing technologies that will refine the delivery of care to patients.

“The science and art of medicine continues to improve in many areas,” say Garry Carneal ’88, president and CEO of Schooner Healthcare Services, a consulting company that helps design medical management systems, health care communications,and technology. “For example, the case management community is doing fantastic things in terms of managing individuals with chronic illnesses, which is a major cost driver for the U.S. health care system.”

|

Carneal hopes that attending physicians and other can leverage more clinical information and other data elements to promote quality-based interventions. “A critical component of any population-based program in health care is to move away from a fragmented and siloed environment to one that is integrated and promotes smooth transitions of care.”

Some micro-models in the U.S. also manage to provide high levels of care at low overall cost. These models correlate closely with local non-profit health care providers that use salaried doctors, coordinated care, and a patient-centered approach, like the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic. These clinics put the patient in the center of a coordinated team approach, offering every type of service under one roof. Since salaried doctors provide the care, they have no financial incentives to push unnecessary services and procedures.

|

The experts in the health care sector are well aware of the successful models. In fact, many in the industry see acquisition opportunities for systems and technologies that work. “Many of the innovations in health care emerge from the private sector. The consensus is that if it’s already built, don’t rebuild it – buy it,” says Carneal. “From a public policy perspective, we need to maintain the right equilibrium between private and public sector initiatives. What venue or combination of approaches will work best? For instance, the new state-based insurance exchanges were originally expected to cover about 25 million Americans, but people forget that most Americans are going to continue buying their insurance through the private sector. We need to make sure that any reform prevents adverse risk selection into any -funded or subsidized risk pool.”

Policymakers are ultimately concerned with balancing feasibility and coverage. The U.S. currently spends almost two to three times as much per capita on national health care (by government and private providers) than other developed nations. At the same time, the U.S. ranks 49th in the world in life expectancy and 46th in infant mortality (CIA Factbook). The country’s insurance model either doesn’t insure or under-insures those who need it most, the indigent and working poor. It tends to over-insure those who need it least, the fully-employed without preexisting conditions (something the Affordable Care Act is designed to correct beginning in 2014).

The U.S. model also causes “job lock” for those afraid of losing their employer-based health care. According to studies conducted for the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), it reduces job mobility by as much as 25%, which lowers overall U.S. labor productivity. It encourages too many expensive procedures that yield few measurable results. It insulates consumers from the real cost of their health insurance by cloaking it within tax schemes and salary structures (e.g., the Milliman Medical Index reports that the actual medical cost in 2010 for a typical American family of four was $18,074, 59% of which came from employer subsidies). It “cost-shifts” onto taxpayers and insurers an estimated $30 billion a year in “uncompensated” mandatory hospital care for those who cannot pay.

|

Bonnie agrees. “Regardless of the differences of opinion that experts might have about health care in the long run and the best approach to these problems, everybody knows that the system has to be changed. It is absolutely inefficient. What we now have evolved over time, as so many things do, and completely lacks coordination and integration. If we were starting over, no one would propose the system we now have.”

“Our national health care system works differently than other nations,” says Bruce Kelly ‘76, recently retired director of government relations for the non-profit Mayo Clinic (sharing his personal opinion, not any official position of his former employer). “Here, the more stuff you do and the more stuff you order, the more money you make.”

Matching Expenses with Results

What constitutes “good” health care is not always obvious. Spending does not guarantee wellness, and may produce no clear benefit. An MRI for a suspicious headache may find nothing that would change the treatment plan, or it might reveal an inoperable brain tumor. Either way, the MRI itself did not alter the ultimate result.

This may seem pedantic, but it is at the root of the “Goldilocks” problem in health insurance: how to create a “just right” insurance policy that covers a person’s real needs, and no more. It further complicates the Affordable Care Act’s mandate to examine “relative health outcomes, clinical effectiveness, and appropriateness” of medical treatments. The tenuous connection between medical cost and benefit complicates that research.

As a result, Americans are usually under-insured for necessities or over-insured for incidentals. That has enormous consequences for health care. According to one study from the NBER, the “deadweight loss” of insurance coverage (receiving more insurance than necessary, or buying too little because of price) is anywhere from $125 to $400 billion in today’s health economy.

Further, a RAND study found that higher patient co-payments reduced significantly the use of medical care, but without affecting average medical outcomes. It also showed that total costs fell as co-payments rose. In fact, contrary to complaints that higher copays reduce access to doctors and increase the likelihood of more expensive hospital care, the reverse occurred. More primary care, not less, led to higher hospital costs, without producing any measurable health benefits.

Using NBER data alone, the optimal insurance policy would have the individual pay medical costs within some affordable range (perhaps using pre-tax Health Savings Account or Flex programs), and then pay in full when the costs became unaffordable. According to free market principles, individuals would choose only those procedures that offered real and transparent benefit, reducing their overconsumption of “premium care” and lowering costs for everyone.

Of course, these problems can’t be solved using economic analysis alone. Instead, politics will guide the process.

A Short History

In spite of the inefficiencies that would seem to attract creative solutions, and general agreement that the system is broken, the public debate about health care reform continues to be, in the main, one driven by ideology rather than by reasoned argument.

“A political system crafted by the founders to resist large-scale reforms,” writes Graetz in Rethinking American Social Insurance: True Security (1999), “coupled with public and politicians’ fears of a ‘government takeover’ of health care, has entrenched our health insurance patchwork in the face of obvious inequities and absurd levels of expenditure.”

|

In 1928, Scottish scientist and Nobel laureate Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin. Before that, doctors performed routine surgeries and emergency care, but could offer only palliative care for almost everything else. Health care occurred mainly in the home, and costs were low. But with penicillin, doctors could cure patients of ailments that had previously killed and maimed. Vaccines and other medical breakthroughs followed. Technology and the growth of cities fueled the need for more and bigger hospitals. In time, health care took on an entirely new meaning and an ever larger role – and expense – in the daily lives of Americans.

In 1929, feeling the brunt of the Great Depression and seeking revenue to keep itself afloat, a hospital in Dallas created a non-profit organization called Blue Cross that allowed 1,300 local teachers to finance up to a 21-day stay in the hospital by pooling small monthly payments. The idea replicated rapidly across the country. Soon doctors followed suit, offering employers the first Blue Shield plan for their workers in logging camps in the Pacific Northwest. In 1934 private for-profit insurers, sensing the market potential, began offering health care coverage to individuals. Health care costs at the time were relatively modest, and risk premiums reflected that.

|

During World War II the government issued wage and price controls to tackle inflation, while allowing employers to offer fringe benefits to attract workers. Employer-subsidized health insurance was one of them. In a move that still shapes the health care system to this day, the federal government then allowed tax deductions on the amounts employers spent on health care. Today, according to an NBER study, employer-based insurance dominates the market with a tax subsidy worth about $200 billion annually.

|

|

Further efforts by presidents Nixon, Carter, and Clinton to institute universal health care were stymied by more political miscalculations, missed opportunities, and AMA lobbying muscle.

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

Americans long ago accepted the need for universal access to emergency health care; ambulances must pick up the sick and dying, and hospitals must take care of them. Further, there will always be individuals who, for some reason or another, fall outside of the system. But providing primary care for them through emergency rooms is ponderously inefficient and shockingly expensive. “We have accepted that you have to have a safety net,” says Bonnie, “but the problem remains that uninsured people can’t afford care that would prevent many of those crises from occurring in the first place. Relying on the emergency department as the sole portal to health care is not good for the patient and it’s not good for the system because we end up paying for it one way or another.”

|

Bonnie counts three challenges to health care reform; access, quality, and cost. The Affordable Care Act took a big step to broaden access, and some steps toward improving quality. “However, there’s not much in the bill designed to solve the cost problem,” he says. “Nobody is willing to step up to the plate and deal with the big problems, but we’re going to have to do that one day.”

Given the historical opposition to health care reform from the traditionally conservative AMA, why did it change its mind and support the Act? Perhaps it was responding to a restless membership. A Robert Wood Johnson Foundation poll found that over 70% of doctors nationwide supported either a public health care system (62.9%) or a public option in an insurance-based system (9.6%). AMA members responded by roughly the same margins.

It was also partly good politics by the Obama administration, which “carved off interest groups one at a time,” says Riley. “The AMA and others saw that if they didn’t establish some equilibrium in the system they had greater risk. The hospitals, the pharmaceutical companies, even the physicians saw these changes coming and saw that they could do well in the system. They were willing to accept regulation to the extent it limited their risk. Where they don’t see risks to their own interests, they’re going to be unwilling to play.”

Even though its many longtime opponents – the AMA, the pharmaceutical industry, health insurers – supported the Affordable Care Act, the new legislation still did not avoid criticism from the political right, historically allergic to government intrusion; or the left, which wanted a larger public role, mainly single-payer insurance.

Riley sees two debates going on. “One is the political rhetoric to rally the base, right and left. The other is the inside-the-Beltway battle between technocrats over privatization versus regulation. That debate actually is reflected in the Affordable Care Act – which is essentially the plan Nixon proposed four decades ago -- where it contains provisions that intersect between those groups. The base doesn’t hear any of this. The public debate is hyper-politicized and yet it has very little relevance to what’s actually taking place in Washington.”

Kelly, a veteran of legislative battles over health care, was in the middle of the Senate discussions. “For all the legislation I have ever had anything to do with, and I have been doing this for over 20 years, the Affordable Care Act was the most difficult,” he says. “It became very big and turned totally partisan at the end. There were attempts to bring some Senate Republicans into the fold. There were a lot of private conversations about finding a compromise position. That’s the normal legislative process, give and take, but that compromise never materialized.”

According to Kelly, if the legislation had focused solely on universal health care insurance, Congress might have produced a bipartisan bill. But the bill began to cover other aspects of reform that invited dispute. “The scope was too broad,” he says. “Everybody thinks it was a bill designed to provide every American with health insurance. That was the main thrust, but only a part of it. There were many other moving parts relating to Medicare and Medicaid and research. A lot of those became controversial.”

For example, the economic stimulus package in 2008 contained funds for comparative research analyzing the efficacy of experimental medical procedures. At the time, opponents of the idea argued that such research was an attempt by the government to ration health care, getting “between you and your doctor.” That dispute carried over into the 2010 health care reform debate. “The bill had a big provision funding this type of research,” Kelly recalls. “That brought in the earlier rhetoric about end of life discussions that got blown into the ‘death panel’ issue. None of those issues had anything to do with universal health insurance.”

Carneal agrees that the rhetoric took over. “My disappointment is that when things get politicized or when people over-emphasize a particular stakeholder perspective, the debate often becomes subjective and biased,” he says. “Among other challenges, any health care reform initiative needs to address a myriad of technical issues and funding challenges that do not always have straight-forward solutions. Public policymakers also need to find the right balance between incremental and comprehensive reforms.”

No public official wants to use the word “rationing,” but health care cannot be reformed without acknowledging the need for an overall health care budget that requires caps on expenditures for procedures and services. Some will cost consumers more. Some will not be fully covered, and others will be excluded entirely. “People can’t have everything they want when they want it,” says Bonnie. “How you make those decisions based on evidence is the challenge that we now face. At least the seeds for it have been planted in the legislation, and it has to slowly trickle into the culture from a political standpoint.”

Ultimately, given the real disagreements about the details of reform, its politics, and the unique cultural and fiscal constraints on providing universal health care, Bonnie believes the Act was a good bill. “Many experts in the field would have preferred something else, but they are generally supportive of the Act. I think that is telling. The experts know the political constraints within which Congress was operating. We’re not going to be single payer, we’re maintaining the health insurance industry, and we’re not fundamentally changing Medicare and Medicaid. That removes a lot of options. But at least, we can begin to solve some of the problems.”

Four Health Care Models

Both sides of the debate cite health care systems around the world to point out what is right or wrong about health care in America. The irony is that these other models are hardly “foreign,” according to journalist T.R. Reid, author of The Healing of America. Americans already use versions of each of them.

The National Health Insurance model (Canada, Australia, Taiwan, South Korea) uses private care providers working within a government-run, non-profit insurance plan (single-payer, or one entity acting as administrator) that citizens pay into on a monthly basis. It uses its superior marketing power to negotiate lower prices. It limits covered procedures to those that meet efficiency guidelines. It is notorious for long waiting times. In Canada, it’s called Medicare, just like it is here for Americans who turn 65.

In the Beveridge model, named after the British social reformer William Beveridge who designed it (UK, Italy, Spain, Scandinavia, Hong Kong), the government uses taxes to finance and provide health care for all. Most care providers work for the government, while some are private. All are subject to government cost controls and fee structures. Patients pay no medical bills. Here in the United States, native Americans, and military personnel and veterans, enjoy the same coverage.

The Bismarck model named after Prussian Chancellor Otto Von Bismarck (Germany, France, Japan, Belgium, Switzerland, Latin America), uses private payers and providers to deliver health care. It sets fees and tightly regulates several hundred private, non-profit insurance plans (or “sickness funds”) to make sure they cover everyone. Except for the “covering everyone” part, this is the primary model in this country for working people under the age of 65.

In the Out-of-Pocket model (most of the undeveloped world), it is pay-as-you-go if you can afford it. 47 million uninsured Americans live under this model, unless they can find a free clinic, get admitted to the emergency room at a public hospital, or suffer from a covered condition and be poor enough to qualify for Medicaid.

In the End, Politics

The Beveridge, Bismarck, and NHI models have their own advantages and drawbacks. Each struggles with rising health care costs. Each reflects unique cultural standards. But all of them share two important characteristics: they are largely non-profit, and they cover everyone. Not so in the U.S. According to data collected by Yahoo Finance, the nation’s health care sector reaps tidy profit margins, about 21.5% overall. Insurance and hospital profits are only about 4%, but pharmaceuticals (23%) and medical devices (12.6%) pull up the average.Profit, of course, is not a bad thing, though the non-profit health care models incur only a fraction of the administrative costs of for-profit providers in the U.S. Further, Bonnie sees the “lines between the two models getting awfully blurry when you look at providers of services.” The Affordable Care Act offers incentives to providers to be efficient, offer high quality, and achieve patient satisfaction. It also fosters competition between providers to allow patients meaningful choice. “When you take all those factors into account, I’m not sure how big a difference there is between organizations that are basically non-profit and those that are not,” he says.

It is a leap, then, to suggest that the free-market individualism so ingrained in American culture would pursue a broad non-profit model. In fact, a variety of business interests and state’s Attorneys General are working to undo the Affordable Care Act. But rising costs, endless tweaking, and fiscal mismanagement in the present system only underscore the gravity of the problem. The U.S. model cries out for reform, yet there are too many competing visions to yield an easy solution. But doing nothing is not an option.

Many on the left argue that health care is a civil right; a basic need that government should provide. Many on the right disagree, seeing too much moral hazard in a system that they believe would reward bad behavior and invite abuse. At bottom, universal health care challenges a host of ancestral beliefs deeply embedded in the culture. People resist arguments that conflict with those beliefs. Health care policy is already hard enough to understand without having to hurdle that obstacle as well.

“It’s a question of first principles,” says Riley. “As one who comes from a liberal tradition, I typically use the metaphor that the Affordable Care Act was a train that needed to be started. Without that train moving a big framework into place, we will get nowhere. We can adjust it as experience requires. My friends at the Heritage Foundation would say we didn’t need the Act, that it contains layers of unnecessary regulations, and better to tweak health care slowly and go only as far as we need to go. Interestingly enough, we’re not that far apart, since we all recognize that the delivery of health care has serious problems.”

|

Kelly also cites one other key problem: the sheer size of the health care economy. “There’s a lot of money at stake for the providers,” he says. “When you start changing the way you deliver and pay for care, somebody’s income is going to go down, and everybody gets into full battle mode to protect their particular turf.”

But the health care industry is moving forward, no matter what, says Bonnie. “It’s hard to imagine as a practical matter how you would now repeal this. The insurance industry, which supported the bill, is adapting to the changes that have already taken effect and is planning for the next round. Many states, notwithstanding the litigation, are taking steps to move forward, and the Obama administration is giving them greater flexibility as it promulgates proposed regulations. Many provider groups are reorganizing themselves to take advantage of incentives created by the Act. At this stage, outright repeal seems more like a political slogan than a real option.”

However, Carneal would prefer a “go-slower” approach from a purely practical standpoint. “The federal agencies are moving forward too quickly to fully vet the best policies to implement. The devil is often in the details. The over-reliance of ‘interim’ rulemaking procedures over the past year has short-circuited traditional feedback loops that are usually required by the administrative rulemaking process. When you rush, you make assumptions which can compromise the end result. In a similar vein, the cost estimates keep changing. Do we really know how much this is going to really cost? ”

For example, most everyone agrees that the insurance exchange concept is a good model, but the path to implementation sets forth many nuances that must be resolved, according to Carneal. “Each state needs to figure out how the exchange models in their respective jurisdictions need to be adopted and run. How will the private insurance market interface with the state-based exchanges? How many health plans can participate in the exchanges? What technological interfaces are needed to track eligibility as individuals move in and out of the exchanges? And so on. As a result, my sense is that many state regulators are feeling rushed due to the Act’s timelines and mandates.”

Kelly also sees the medical profession moving away from the solo and small group practices that have traditionally dominated AMA membership. “There are growing numbers of salaried doctors in multispecialty clinics, like Mayo,” he says. “That’s the dominant model for health care delivery in the Pacific Northwest, in the upper Midwest, and other areas. That model is spreading.”

Given the political confines in which health care reform must function, Bonnie is hopeful. “I think that the Congress did a reasonably good job putting a plan in place. Things are moving along. You’ve got administrative structures that are hopefully going to continue to make it work. There may be tweaks that Congress needs to make from time to time, but that’s the way things work. I think that this is a reasonable reform that has a realistic prospect of being successful.”

“Ultimately, I have faith in the political process even though it appears to be very partisan these days,” adds Carneal. “We need to work through all of the key decision points in an objective and systematic manner. The current health care reform debate has created an important national dialogue. It is imperative that we take the time to effectuate meaningful change that promotes higher quality care and more consistent coverage for all Americans.”

Reform and Rhetoric | Constitutional Question| ACA

Summary | Accountable Care

Organizations | Mental Health Care Reform