Before there was Black Lives Matter, there was another sweeping social movement led by African-Americans. The movement’s aim — as the civil rights era matured and the 1970s approached — was to recruit, train and promote black attorneys within the legal establishment in the interest of greater opportunity and justice for all.

At law schools, the Black American Law Students Association was at the forefront of that movement.

Students at UVA Law organized the school’s BALSA chapter on Friday, Oct. 16, 1970 — two years after the original chapter began at New York University and following the establishment of chapters at other major law schools.

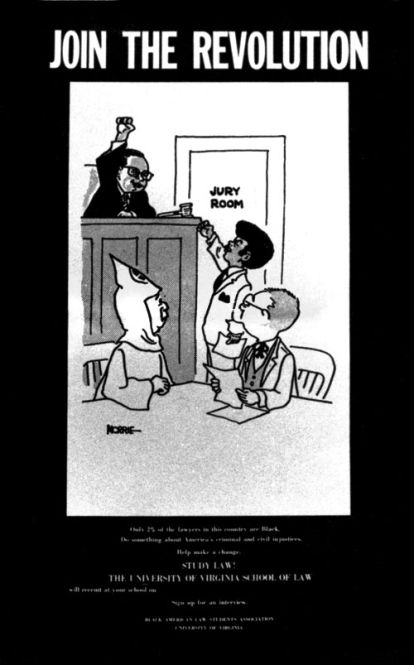

A BALSA poster designed to recruit UVA Law students said: "Only 2% of the lawyers in this country are Black. Do something about America's criminal and civil injustices. Help make a change. STUDY LAW!"

Eschewing a top-down approach for a more egalitarian style, the students elected Albert L. “Skip” Preston ’71 as their “convener,” rather than president. In addition, Gloria H. Bouldin ’73 was chosen as secretary, with Class of 1972 members Gwendolyn L. Jones, S. Delacy Stith, Jack W. Gravely, Bobby N. Vassar and Leonard McCants selected as committee chairs.

The next week, and regularly from then on, the Virginia Law Weekly chronicled the student group’s efforts to promote a more equitable learning environment at UVA. The Weekly, paraphrasing BALSA public relations chair McCants, stated that “the Black students needed a formal body to channel their energies toward united solutions to problems.”

Numbers were the group’s most pressing concern. Among the Class of 1970, there were only two black students. (Elaine Jones and James “Jimmy” Benton graduated that spring.) The incoming class for the 1969-70 academic year included a group of 13 black students. Both in law schools and in the legal profession, blacks were thought to have had about 1 percent representation, despite their much higher numbers in the greater population.

On the UVA law faculty, there were no black professors.

By the fall, the faculty’s appointments committee acknowledged the hiring problem, and set recruiting the first black professor as a goal — albeit one that seemed without a timeline.

<p>In an editorial, the Law Weekly de­fended the faculty’s efforts as methodi­cal, rather than gradualist. But in an Oct. 16, 1970, response, African-American students blasted what they viewed as tone-deaf commentary. “At Virginia, we need a change of heart, a firmer and less rhetorical commitment to equal op­portunities which will be reflected by the hiring of Black law professors here in the halls where justice is taught.”</p>

The letter was signed, “The Black Law Students at U.Va.”

In 1971, publicist McCants and fellow third-year Norman Davidson, a white student and president of the law student council, formed an ad hoc committee for the recruitment of black professors. At the time, there were two black lecturers, who were not part of the full-time faculty. They each served only the duration of their courses, one semester.

Of the potential full-time candidates, “Many of the attorneys will in all probability be engaged in active urban practices,” Davidson said. “[Our] student interest might be one of the factors in their decision.”

By 1972, a white student writing for the Weekly penned, “After two years of diligent searching for a black professor, the Law School faculty is still lilywhite and is likely to remain that way for the immediate future.”

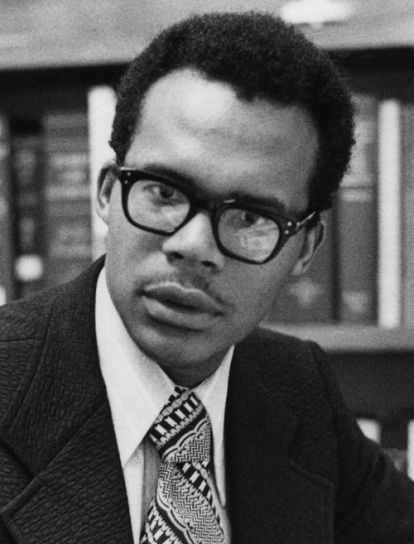

Professor Larry Gibson

The article indicated that part of the problem was that the hiring committee was reaching out to their peers among top law schools, where there was already a shortage of black professors. Still other potential candidates felt ill-at-ease in the South, according to Associate Professor Jerry L. Mashaw, who chaired the subcommittee on minority recruitment.

“Professor Mashaw said that one highly desirable candidate stated outright that Washington, D.C., was as far south as he would go,” the article read.

But Vassar, who had become BALSA’s convener in his third year, told the Richmond Times- Dispatch that the “difficulty of the task should not be used to excuse the lack of results.”

BALSA had presented the hiring committee with a list of 50 potential professors who the group felt were qualified to teach various subjects; many of them were not contacted, Vassar told the Weekly.

By March, BALSA took a more aggressive stance. It called upon state officials in a pointed letter to begin a “formal investigation” into the Law School’s hiring practices, which the group followed with a related press conference two days later

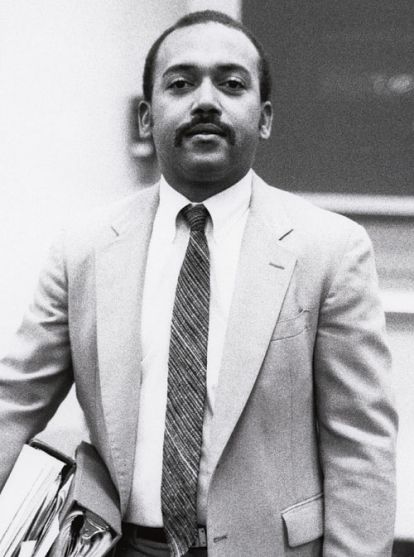

Professor Alex Johnson

It also called for a moratorium on hires until a black faculty member was chosen.

Through student council, BALSA had demanded the addition of qualified black faculty by the following September, leaving the Law School community to wonder what action they might take if their demand wasn’t met.

The pressure they applied worked. UVA hired Larry Gibson, a graduate of Columbia Law School, who left the Baltimore law firm where he was a partner to accept the teaching position. (Two years later, Gibson accepted a faculty position at the University of Maryland School of Law, where he continues to teach. He is also of counsel at Shapiro Sher. He returned to UVA for a semester as a visitor in 1977.)

The hiring of black faculty continued to be spotty as the years progressed.

Samuel Thompson was the first African-American tenured professor at UVA Law. (Thompson started in the fall of 1977 and left Virginia in 1981. He would later serve as dean of the University of Miami School of Law. He is currently a professor at Penn State Law School.)

After Thompson’s departure, it took two years for UVA Law to hire a black full-time professor again, with the addition of Professor Alex Johnson in 1983.

Growth in black law student numbers at UVA Law also came more slowly than BALSA would have wished. But BALSA continued to reach out to black prospective students as part of annual recruiting efforts, and remained outspoken about student and faculty representation.

In 1983, National BALSA removed the “American” from its name to be inclusive of black members who are not of American nationality. That change is reflected in the current UVA BLSA, an award-winning chapter that has operated at the Law School for almost 50 years.

Read More

- The Long Walk: How Gregory Swanson Integrated UVA and UVA Law

- Saying ‘No’ to Wall Street and ‘Yes’ to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund: Elaine Jones ’70

- ‘I Represent All the Students and This Is What I Want’: Linda Howard ’73

- One Student’s Debt: Alfonso Carney Jr. ’74

- Erasing the Color Line: Ted Small ’92 Looks Back on SUPRA

- The Great Indoors: REI General Counsel Wilma Wallace ’89

- The Jacksons’ Judicial Philosophy: Raymond ’73 and Gwendolyn Jackson ’72

- Generation Next: The Phipps Family

- Standard-bearers: Outstanding Black Alumni

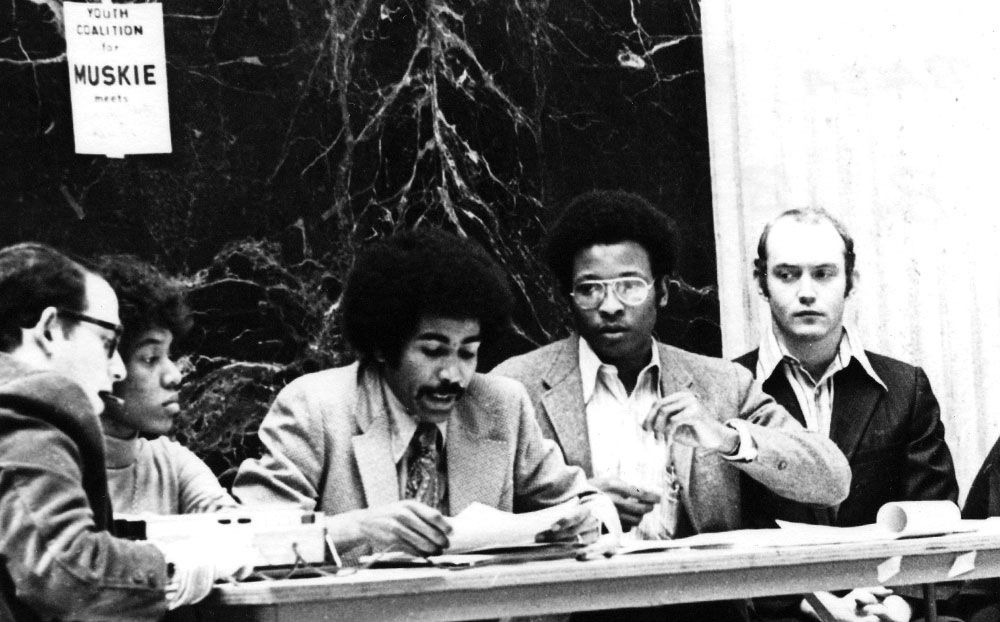

Bobby Vassar ’72 on the BALSA Press Conference

<p>Bobby Vassar '72, middle, speaks at a press conference called by BALSA. To the left and right of Vassar are Margaret Poles Spencer '72 and Leonard McCants '72.</p>

Everything had to be perfect if the March 21, 1972, press conference in Clark Hall was to have its intended effect.

“We were dressed for the occasion, looking professional, and made sure our materials were grammatically correct and accurate,” said Bobby Vassar ’72 in recalling the culmination of BALSA’s campaign to see a black faculty member hired at UVA Law. “We made sure we did all the things we thought would make it credible.”

Not only did BALSA have the ears of state and federal organizations that dealt with discrimination, to whom they were sending their letters of complaint, but they also had the eyes of the news media, some of it national.

“We understood there was boldness and some audacity, but that was how you did things back then,” Vassar said.

He didn’t recall much nervousness among the group as they challenged the administration, however.

He didn’t recall much nervousness among the group as they challenged the administration, however.

“By this time I guess we were seasoned,” he said. “I think we had no expectation that it was doing anything other than what ought to be done. We couldn’t be here seeing a situation that shouldn’t be that way and not do something about it.”

The press conference took place on a Tuesday afternoon.

“The next day, Wednesday, Professor Gibson from Baltimore, who had taught a course at the Law School, was on the campus and came by to see us to tell us he was offered a job starting the next semester,” Vassar said.

The lecturer and law firm partner told the students the dean made him “an offer he couldn’t refuse.”

Vassar went on to become a public interest lawyer. His career spanned from being a legal aid attorney in Roanoke, Virginia, just after graduation, to recently retiring as Democratic chief counsel for the Subcommittee on Crime, Terrorism and Homeland Security of the U.S. House Judiciary Committee.

He continues to work part-time as senior counselor for Bay Aging, a Virginia Area Agency on Aging, and volunteers as a member of numerous government and nonprofit boards and commissions.