Cowan Fellow Brian Kennedy Shares Travelogue from Human Rights Research Trip to Ghana

Third-year law student Brian Kennedy, a 2013-14 Cowan Fellow and president of the student-run Human Rights Study Project at the University of Virginia School of Law, wrote a detailed travelogue of this year's research trip to Ghana. For Kennedy, the visit to the country was his fourth.

Stories from Ghana

By Brian Kennedy

In Motion.

How will I get there? This is a defining question every day in Ghana, because it determines how hot you will be, how much you will pay, and how small a space will be allotted for each traveller. Unfortunately, the one thing that it does not very much affect is how fast you will go. Because if there is one downside that sinks the excitement of progress, it's the paralyzing imbalances of development. When the cars multiply faster than the roads widen, everyone slows, often to a halt. This is an equal opportunity frustration for those on the move: whether you drive a Mercedes or ride in the back of a bus, it often takes hours to travel the distance of a few miles.

But there are choices. The first choice is the ever-present taxicab. As in Manhattan, these make up the majority of the cars in Accra. Always with orange colored corners, often missing parts, never without character. Most have a slogan emblazoned on the rear windshield, so when hailing a cab you can choose to ride "American Dream" or "God Power" or "Daddy Pee" to your destination. If the driver has survived Accra's streets for several years, he will often celebrate his fortune by appending "still" to the beginning of his slogan: "Still Bro, Please." Drivers work hard to earn this title, often showing Rube Goldberg-inspired talent for improvisation and creative fixes. When one of my drivers rear-ended a log by accident, he used a pen cap as a screw to re-attach his rear bumper in less than 2 minutes. When that plan unraveled a kilometer down the road, he quick took a piece of rope from his driver door compartment and tied his bumper to the roof of his car. On we went. Survival in this context is defined by an engine that turns wheels, most everything else is optional. After 197,000 miles, my friend Asare's car jerks so violently in first gear that the whole car shudders and the gear shifter often shakes itself back into neutral, forcing Asare to jam it back into gear. But it still rolls, so it survives.

Taxicabs are still my favorite, because they offer a chance to sit next to an open window and often an interesting conversation, if the driver speaks English. But occasionally we take the cheaper option, called tro-tros. These are the Ghanaian equivalent of public buses. They are minibuses that leave only when they are full, meaning that if you are unlucky enough to be the first to board you could be waiting hours before the bus leaves. Recently we heard a few rules of tro-tro riding from the Tro-Tro Appreciation Society that are worth sharing: “Time does not exist in the tro-tro universe. It will leave when it’s full, and it will get there sometime after that. The optimum temperature for the inside of a tro-tro should exceed that of the core of the sun, so all passengers can sweat freely on their neighbors. A person occupies a seat. If you have luggage as big as a person, you must still wedge it on your knees until your toes turn blue. Goats must be tied to the roof. In the event of a crash, under no circumstances should a tro-tro pull over: it must remain in the middle of the road until the drivers have finished fighting. A speedometer is an unnecessary distraction. The speed settings are “regular,” “fast,” and “crashed.” In order to optimize the “experience” of Ghana’s roads, no tro-tro should employ suspension of any kind. A gear stick should have anything but a gear knob on it, for example a tap or a golf ball. A tro-tro is made up of 40 percent seat, 10 percent wheels, 20 percent (and falling) floor, ceiling, and sides, and 30 percent rope/duct tape.”

After you figure out your transport, the next important question is how to tell the driver where you want to go. Addresses, as we understand them, are a rare gift bestowed upon only select buildings on the main thoroughfares. As a result, Ghanaians think about space differently. Grids or maps with roads names do not seem to exist in their heads; I’ve gotten three different answers to the question “what is the name of the road we are on right now?” Instead, space is defined by landmarks and directions. So when I asked my friend Eric for the address of his house, I kid you not, this is the response I received via text: “Get to Nungua police barrier drive down for four hundred meters and turn onto buade road on your right. Drive on the buade for six minutes and ask for nana asantewaa spot. At the spot ask for Kwabena and ask him to bring you home.”

All this is to say that when we needed to travel to the city of Kumasi on a Saturday morning, a 4.5 hour drive north of Accra, we decided to opt for the most reliable long distance choice: STC buses, which are modern coaches with air conditioning (!). Since traffic yields for no one, and since we only had a 48-hour window to escape Accra, we decided to wake early and beat the morning traffic, which in this city means up at 3 a.m. to be on the road by 4:30. When we boarded the bus in the dark we were pretty pumped. This Korean-made bus, named Big Albert, came complete with frilly tasseled curtains and huuuge reclining seats! We'd be able to steal a couple more hours of sleep and still be in Kumasi in time for breakfast.

How little we knew. I opened my eyes as the bus pulled over to the side of the road. The clock above the driver read 6:47 a.m. I didn't realize the engine had been turned off until it turned over, wheezed for a few seconds, and then stopped again. One more time, same result. Silence. Uh oh. Scott, my friend and fellow traveler, looked out the window and remarked that at least we were stopped in a beautiful spot: thin morning mist was hanging above rolling hills covered by a lush green layered forest. At this point I figured I wasn't going to be the one to fix the bus, so I fell back asleep. When I woke up again we were four out of the remaining six on the bus. Out front a crowd of women stood aside the road, and several other buses had pulled over in front of us. We scrambled out of the bus thinking maybe this was a new bus, sent from a magical nearby parking spot to save us. No such luck. These buses had their own haul, of course, but were stopped to offer supplies and engine fixing advice. When we got out of the bus I realized why the crowd I had seen had been exclusively women: save for the one pastor standing near the door, every single male passenger was huddled around the engine compartment offering their opinion about which part needed fixing. Scott said he wasn't about to have his credentials questioned, so he went to the back of the bus and joined the mechanics' gallery. When he returned, he said "if I know bus engines, and Twi (the Ghanaian language), we have a fuel filter problem."

A few minutes later the offending filter had been replaced, or maybe just removed, and the driver tried again several times to restart the engine. Each time was weaker, prompting the mechanics' gallery to begin a rapid chatter of Twi interspersed frequently with the word "battry." Truth. I thought the battery was dying too.

At this point many of the passengers started to board the two buses ahead of us, but the idea of standing for the four remaining hours of our ride in the aisle of an already packed bus was too unappealing to think about. So as we were looking at the sad drooping rearview-mirror ears of Big Albert and thinking about those reclining chairs inside, we decided not to abandon him just yet. But a jumpstart attempt from a third bus, which blocked the entire Accra-Kumasi road for a time, did nothing for the "battry," so we reluctantly said goodbye to Big Albert and boarded Jesus Yea. Standing was still not an option so we sat cross-legged, one in front of another, in the aisle of the bus, and settled in for the ride. Once I rediscovered the old elementary school trick of tightening the arm straps of my backpack around my shoulders so that I could lean back against it and rest my head on its top edge, I was in business. I passed the time examining the footwear of my Ghanaian neighbors and trading crackers with my obruni (white man) friends for breakfast--not quite what we had planned for the morning. But when we pulled into Kumasi at noon I was pumped again. We travel to find the unexpected. A few hours and two numb butt cheeks was a pretty good price to pay to find it.

On Shopping.

If traffic is an equal opportunity offender in Accra, street shopping is an equal opportunity diversion for the delayed. Unlike in the West, where shopping is mostly confined behind the closed doors of air-conditioned stores, in Ghana (as in other countries on the continent), products are placed as near as possible to the street, and more often than not, in the street. Sometimes it seems that the whole commercial enterprise of Accra is carefully designed to intercept the traveller.

Appliance stores display washing machines and microwaves alongside the road in rows and stacks. Small corrugated-tin shacks hang their wares under brightly colored signs that amuse and confuse foreign eyes: "Jesus Loves You Cold Store," or "B.B.'s and God's Enterprises."

But by far the most common and convenient way to shop in Accra is to buy from ubiquitous hawkers who roam the streets near crowded intersections. Everything is for sale. During my time here I’ve seen ties and socks, bras and belts. I’ve eaten lusciously fried Ghanaian dough balls (Bofroot!) and thought about purchasing FanMilk, a semi-melted ice cream treat that sits stacked in small bags in glass cases under the heat of the sun. If you know where to look, you can plan your route home to pick up everything on your shopping list. One intersection specializes in speedy carwashes; another hawks educational posters on subjects ranging from depictions of the human anatomy to maps of African dictators.

Outside Accra, some entire towns have adopted the strategy of specialization: Everyone knows the one on the road to Kumasi that sells sugar bread. As you pass through this town, you come upon a dozen ladies, all carrying hyper-sweet loaves of white bread in bowls on their heads. Imagine growing up in sweet bread town! And its not only bread that goes on heads either. From jugs of water to stacks of food and even steel doors, everything is held aloft for hours on end by the steady support of a strong neck.

Want something? Just look at them. That's usually enough to get your target to approach, but if it doesn’t, raising a finger or sticking your arm out the window will grant immediate service. Whatever it is that you desire will be stuck through your window and placed on your lap.

The practice of street hawking is more than just a convenience for Ghana's many waylaid travelers. It is a temporary stop-over to more rewarding work for some, a source of supplemental income for others, and a way of life for many. As a result of a population boom, the youth dominate the demographics of Ghana: 40 percent of the population has not yet reached age 14; more than half have not yet reached age 24. But these youth are maturing to working age in numbers that the economy can’t absorb, so whether educated or not, many are left jobless. Street hawking is the ever-present symbol of Ghana’s informal sector.

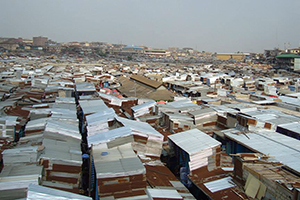

But for all the convenience of street shopping, the ultimate Ghanaian shopping experience is Kejetia market in Kumasi. It is the mothership of markets: the largest open air market in West Africa. From the roof of a building on its fringe, the market looks like a vast sprawling platter of tin roofs, a patchwork of rust and silver that stretches as far and wide as a neighborhood. From here the madness below is only hinted at by streams of people flowing in and out of the broad streets surrounding the market.

Into the labyrinth. It's Fast. Tight. Hot. Close. Shoulders brush. Faces appear and disappear like a flipping rolodex. Sweat flicks from a forehead onto my arm. Thirty loaves of bread pass within inches of my head, piled high on top of another's. But now that head is gone and here's another, this one with a tower of metal fittings--sidestep that one quick--tuck your foot into the nearest shop because the passages are narrow, hardly wide enough for two bodies. If you are not quick enough to dodge, you will be pushed. There is neither time nor space for obruni novices in here. Now comes the smell of meat. Sharp, pungent, this smell does not waft. It surrounds and attacks, sinking into your stomach and filling your head. For a second I am light-headed, even a little dizzy. All the colors blur as they pass, but they do not slow; they do not stop. This market never stops.

Somehow this madness hides a carefully defined order. We are in the toiletries section now. Soaps, shampoos, creams and cheap hairbrushes are packed tight into the stalls. The same products are repeated stall after stall, aisle after aisle. It is not a toiletries store but a toiletries neighborhood, a market within a market. Out of toiletries and into linens. Out of linens and into golden jewelry. A thousand cheap pieces above, below, around. Each type of ware has its place, but the directory is tucked into the minds of those who inhabit this place, and so it is invisible to us. Directions would be useless. The only way to escape is to enlist the help of someone with one of these maps in his head, following him close as he ducks right past the leather shoes, and left past the bootleg DVDs.

These crazy markets exist in Asia and the Middle East and around the developing world. The speed and tight spaces are the same, even if the faces look different and the spices share a different aroma. But my friend Juliet observes one thing that seems to make this one unique, apart from its overwhelming size: there is no tourist section here. There are no African masks or other trinkets in traditional shapes to cater to outsiders. This market feeds Ghanaians and clothes Ghanaians. It breathes Ghanaians.

On Giving.

I do not know the name of the young man who sits on a log and whistles at me as I walk by. Who calls to me: "Obruuuni." Who makes an exaggerated sad face, reaches his cupped hand to his mouth in a feeding motion and calls a second time: "Give me money." He is not thin. He is strong.

I do not know the name of the child who calls me by the same name, Obruni, but follows her call with a smile, a laugh, a vigorous wave, and a second call: "Obruni how are you?!"

I do not know the name of the toddler who stops dead in his tracks at the first sight of me. The toddler who falls silent, whose eyes widen in amazement, unblinking, locking on mine until I am out of sight.

Ken is the name of the taxi driver who has become my friend. When I first flagged him down on a crowded street and asked him to take us home early during our stay in Accra, he did not attempt to inflate the price because my skin was white. Unlike almost every other driver, he accepted the first price I suggested to him. Like many, he was friendly and welcoming. But unlike many, he spoke English well. Ken is half Ghanaian and half Filipino, but he had never left Ghana. I called him almost every day, and he came each time I called. One day, I invited him to pick my lunch place and join me for the meal. As we sat on plastic chairs and ate jolloff, a spiced rice dish, one of the ladies who worked at the roadside stand looked at Ken and asked: Are you Ghanaian? Ken smiled and responded in Twi. The lady laughed and pointed at Ken's light skin in protest. Ken responded once again politely in Twi. I asked the lady in English: if Ken was born in Ghana what made him any less Ghanaian than she? The lady could not respond, but her co-workers began to laugh at her this time. Ken turned back to his jolloff. I asked him how often that happened and he shrugged and said with another smile, "all the time."

Ken always accepts what I offer him at the end of each day. I do not know if my payment is enough, but I know that it's less than I would have to pay most other cabs for a day's work. One day, when I decide to stay home, my friend Juliet calls Ken to drive her to town. At the end of this ride, he has a demand: the same price I have paid, even though he has done only half of a day’s work. Juliet resists, feeling surprised and slighted at his willingness to push her for money when he had not done the same to me. She pays him nearly the amount he has asked for anyway.

At the end of our stay, Ken has a request for me: a memento, something to remember me by. He wants my water bottle. I give it to him.

Jamil is the name of day guard at the first house where we stayed. His father is Nigerian. He too was born in Nigeria. His mother was Ghanaian. She died in Nigeria two years ago, after Jamil had moved to Ghana, he tells us. Jamil is a soccer player. He plays every day. The game pays him no money. Still, soccer is his career, he tells us. When I return from my morning runs, we train together, doing jumps and push-ups and stretches. As the days go by, his approaches grow bolder. His request: to get him a spot on an American soccer team.

Zachary is the name of the night guard. He arrives at dusk each day on a rickety old bicycle, greeting us with a long, arcing wave. His English is broken, but his smile must be among the widest in Ghana. As night falls, he sets up a mosquito net on the cement driveway, tied on one end to his bike seat, and on the other end, to the door handle of the guard shack. Inside the net, he lays a towel on the ground. This is his bed. He asks for nothing.

Many of the people that I met in Ghana became friends. Most own less that I do. Some ask me to give them things, others ask for nothing. All made me wonder: to what do I owe this person? My friendship? A gift? Money? My choices differed from day to day and person to person. I felt empty when I sensed I had paid too little. I felt cheated when I thought I was asked for too much. When I was honestly treated, and I chose to be generous, I felt full. Satisfied.

But the choices don't get easier. Often I wonder whether I've done right or whether I've done wrong. I wonder whether that distinction is even possible to find. The only thing I do know is this: these dilemmas I’ve faced have stretched my heart. And the stretching of my heart has made it stronger.

For more about the research conducted on the trip, read the related story, Cowan Fellows Survey Human Rights Concerns in Ghana.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.