His work has explored boundaries of war and pathways to peace. Professor John Norton Moore is an influential figure in the realms of national security and oceans policy who is celebrating 50 years of teaching at the University of Virginia School of Law.

Having taken academic leave at various times in his career to serve in key government posts, Moore launched the U.S. Institute of Peace, led law-of-the-sea talks and was involved in drawing new boundaries for Kuwait following the first Gulf War.

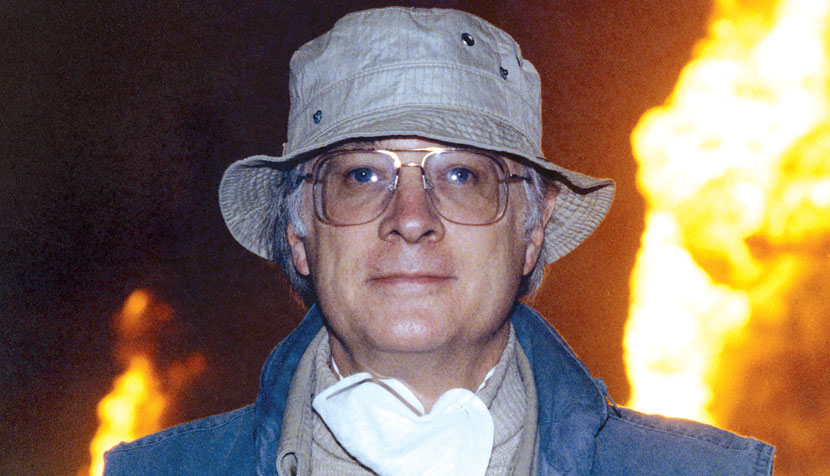

Moore stands in a burning oil field toured immediately after the liberation of Kuwait. “It was hot,” he said.

Moore stands in a burning oil field toured immediately after the liberation of Kuwait. “It was hot,” he said.

At UVA, Moore leads the Center for National Security Law and the Center for Oceans Law and Policy. As the Walter L. Brown Professor of Law, he teaches classes in those two subject areas, as well as seminars on the rule of law and the avoidance of war.

He also leads a class on the legal and policy issues behind the Indochina War, focused on American involvement in Vietnam — the subject where he first made his mark. Moore taught the first course in the country on national security law, and conceived and co-authored the first casebook on the subject.

“Few members of the legal academy have had as profound an influence on law in action as has John Moore,” said Professor A. E. Dick Howard, a contemporary of Moore’s at the Law School. “He virtually invented the field of national security law, in which he enjoys an international reputation. Our Law School can count itself fortunate to have had John Moore here for all these years.”

From Florida, to Yale, to UVA

Moore’s journey to becoming a renowned international legal scholar began in his late 20s, and seemingly at random. As an associate dean at the University of Florida School of Law who earned his LL.B. from Duke University, Moore was an expert in real property, not international law. That changed when he attended Yale University under a fellowship that also allowed him to audit classes of personal interest.

“I was just incredibly turned on by everything at Yale,” Moore said. “I think I audited two-thirds of the curriculum.”

One of the classes he took in 1965 was International Law and International Relations, taught by Myres S. McDougal, a leading international lawyer. U.S. military action in Indochina was being branded as illegal by some, and the professor asked Moore to write a “more balanced piece” on the issues.

Little did Moore know that the request came straight from Lyndon B. Johnson himself.

Moore has been a recurring commentator on national security law issues.

Moore has been a recurring commentator on national security law issues.

“I didn’t realize at the time I was doing it at the behest of the president of the United States,” he said.

Moore was honored to be asked to help on the hot-button topic, he said, where he found solid legal justification for U.S. intervention.

“That ended up being a very major part of my work over the next three or four years,” Moore said. “I was one of the few in the debate who was supporting the legality of the United States’ effort in Vietnam. Not supporting all of the policy, and certainly not supporting all of the violations of the laws of war, such as in My Lai [where the infamous massacre of noncombatants occurred], but basically supporting the overall legal outline for war, which has stood the test of time well.”

The American Bar Association adopted Moore’s guidance as its official position on the conflict. His work entered the congressional record as government officials, scholars and the media parsed the merits.

“Here I was a very young property professor, and now all of a sudden I am an international lawyer, and debating all of the top international lawyers in the United States,” he said. “That was really the starting point of my involvement in what became national security law.”

With the white paper serving to advance his career, Moore accepted a job offer from UVA in 1966, in part to be closer to his family, he said. He began teaching real property, trusts and estates, and shortly after, international law courses.

As the 1970s began, Moore was also asked to serve his country. For a year he provided counsel on the Vietnam War and other international law matters to the State Department as its counselor on international law, before being put in charge of a new office, Law of the Sea.

D/Los and the Law of the Sea Treaty

From 1973 to 1976, Moore was chair of the National Security Council Interagency Task Force on the Law of the Sea — dubbed D/Los for short. He simultaneously served as ambassador and deputy special representative of the president to the Law of the Sea Conference.

Moore’s NSC task force did the preparatory work for what would become the Law of the Sea Treaty. Adopted by the United Nations in 1982, the treaty established a comprehensive set of rules governing the oceans. Nine committees of Congress monitored the work of Moore’s group on a daily basis.

“We were negotiating with over 130 countries in the world,” Moore said. “Basically we were negotiating a constitution for two-thirds of planet Earth.”

He said the efficiency of his office was a source of pride.

“I could get a request at 6 p.m. Friday evening from the Senate Foreign Relations Committee to testify at 9 a.m. Monday morning, and we could clear it through 18 different agencies and give testimony Monday morning that had been fully cleared,” Moore said.

But he said the highly organized operation came together in a somewhat serendipitous fashion.

“The way that office was set up was one of the most effective ways we’ve ever run anything in the U.S. government — probably by accident,” Moore said. “I don't think anyone had the genius to see this was going to work that well. But had we not had that interagency office, I don’t think we would have had the Law of the Sea Treaty.”

Moore said the U.S. informally abides by the treaty, despite the Senate having never ratified it (conflicts over sea-bed mining remain a sticking point), and it’s widely observed around the globe.

“Probably after the United Nations Charter, it’s one of the two or three most important treaties in the world,” Moore said.

After D/Los, Moore conducted nonpartisan policy research at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars before returning to Virginia.

Founding the Two Centers

Moore set up two nonpartisan, nonprofit interdisciplinary centers at UVA after his return that have helped shape their respective areas within international law.

In 1976, he founded the Center for Oceans Law and Policy, which supports research, education and discussion on legal and public policy issues related to the seas. Considered the premier center of its kind worldwide, it sponsors or co-sponsors an annual conference on a topic of international concern, presents the annual Doherty Lecture in Washington, D.C., and offers a summer academy in Rhodes, Greece, among other programs. In addition, the center is famous for its “Commentaries” series, which is an article-by-article analysis of the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea.

“It’s not an exaggeration; there’s nothing close,” Moore said. “The oceans center is the best in the world. We so clearly have the top international conference that the United Nations decided last year to co-sponsor it with us, which they have never done before.” The event took place at U.N. headquarters.

The U.N. General Assembly also recently issued a resolution commending the Rhodes Academy as a training center for U.N. diplomats and others in oceans law.

In 1981, Moore founded the Center for National Security Law to advance scholarship and education on issues affecting U.S. national security. Among its programs, the center participates in an annual review of the field, sponsored by the American Bar Association (which honored Moore for his career contributions to national security law in 2013), and hosts the popular National Security Law Institute for professionals during the summer.

The first of its kind in the U.S. when it began, the center has since provided guidance for starting other successful national security law centers, including those at Georgetown and Duke universities.

“One of our objectives was to create the new field of national security law and help people set up centers of excellence in the field,” Moore said.

USIP, Democracy and the Rule of Law

Once the centers were securely operating, Moore returned again to public service. From 1985 to 1991, Moore chaired the board of directors of the U.S. Institute of Peace. The nonpartisan federal institute, founded by Congress in 1984, conducted early research on how wars begin, and continues to do research and training on the rule of law.

“My greatest professional satisfaction in life is the enormous success of the United States Institute of Peace,” Moore said.

Moore’s current colleague at the Center for National Security Law, Professor Robert F. Turner, served as the institute’s first president. Moore said the institute deserves credit in the calls for democracy heard around the world.

“We began the modern push for democracy and the rule of law — the whole movement that actually swept the world,” Moore said. “Now of course we’re seeing an enormous amount of pushback on that from [Russian President Vladimir] Putin and others. But it was an enormously important movement. That’s a story that’s never been told, but that came right out of the U.S. Institute of Peace.”

From his work at the institute, he was asked to chair, with the deputy attorney general of the United States, the first talks between the U.S. and the then-Soviet Union on the rule of law. Moore decided it was important as a prelude to the talks to make an argument for economic rights, especially property rights — subject matter some considered too taboo to broach with the Soviets.

“The State Department was nervous,” Moore said. “They said to me, ‘Don’t you know this is a Communist regime?’ I said, ‘I think I’ve read my Marx and Lenin.’”

To State’s surprise, the official response from Moscow to adding economic freedom into the talks was encouraging; Moore recalled it this way: “We now believe the absence of property rights destroyed civil society in our country.”

He added, “I sent a response back saying, ‘The revolution is here.’”

Moore said the policy exchange was influential in the 1990 conference that produced the Copenhagen Document, which establishes the internationalization of democracy and the rule of law.

Moore traveled to Russia in 1991 for the in-person talks, which he co-chaired. His Law School colleague Howard, an expert on constitutions, was also part of the delegation.

“Traveling by train from Moscow to Leningrad, John and I found ourselves locked in our railway carriage,” Howard said. “We could not help but compare ourselves to Lenin, who famously was locked in a railway carriage bound from Zurich for Petrograd. Lenin’s trip helped fuel the Russian revolution. John hoped to fuel another kind of revolution — a move toward constitutional democracy in Russia.”

Moore’s most recent government service was from 1991-93, during the Gulf War and its aftermath. He served as the principal legal adviser to the Ambassador of Kuwait to the United States, and to the Kuwait delegation to the U.N. Iraq-Kuwait Boundary Demarcation Commission.

Moore has held six presidential appointments in total.

In addition, under the aegis of the nongovernmental organization Freedom House, Moore initiated and wrote the first draft for what became The Community of Democracies. Founded in 2000, it's now a functioning international institution made up of democratic countries that meet every year.

A Legacy on Paper, and in People

In the centers’ combined offices at the Law School, there’s a photo from Kuwait — a mired tank in the foreground, a burning oil well on the horizon. Moore took that one himself. Other photos depict Moore giving talks or attending high-level meetings. And there are plenty of books — so many that the third floor Slaughter Hall digs could be named their own branch of the UVA Law Library.

Moore himself has authored or edited more than 40 books, including the ground-breaking casebook “National Security Law” (1991), now in its third edition. He also sees “Solving the War Puzzle” (2004) as among his most important works, because of the theories it advances on the causes of war, and how to prevent them.

He has authored more than 200 articles, monographs and book chapters. He is also a member of advisory and editorial boards for nine journals and numerous professional organizations.

But perhaps as important as his government appointments and thoughts on international law are the people whom he has influenced. Past students have gone on to senior positions in the government, the military and at nongovernmental organizations.

James Kraska LL.M. ’05, S.J.D. ’09 teaches at the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law at the Naval War College. He's also a senior fellow at both of the centers Moore created.

“There’s literally hundreds, if not probably thousands of people who work in areas of international law who have been influenced by him — some of them profoundly — including myself,” Kraska said.

As a young officer in the JAG Corps, Kraska attended the third National Security Law Institute, held in 1993. He was so impressed by Moore and his work on the Law of the Sea Treaty that he chose to study under Moore twice at UVA.

“His teaching schedule is kind of legendary,” said Kraska, whose S.J.D. dissertation was published by Oxford Press in 2010. “He must have taught more people in international law than any other professor in the United States.”

Retired Army Brig. Gen. Richard C. “Rich” Gross ’93, a distinguished fellow at the Center for National Security Law and a partner at Fluet Huber & Hoang, said Moore had a “tremendous influence” on his path. As a law student, Gross was an Army captain looking forward to a career as a judge advocate. His final active-duty assignment after more than 30 years of military service was as legal counsel to the president’s top military adviser.

“I thought my focus in the military would primarily be criminal prosecution, but Professor Moore’s class opened my eyes to a whole new world of international law, national security law and the law of armed conflict,” Gross said. “Professor Moore’s textbook remained on my bookshelf throughout my career. His teachings became particularly important to me after 9/11, as I began a series of assignments with joint and special operations units, culminating as the legal counsel to the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.”

Gross praised Moore for his forward-thinking approach to the field.

“Nowadays, it seems every law school has a national security law program; however, Professor Moore was an early pioneer in this important field, and the UVA Center for National Security Law set the standard for the other programs that followed,” Gross said. “Over the years, Professor Moore has contributed a wealth of scholarly thought to the field of national security law; more importantly, he has made the academic practical and applicable to those of us who practice in the real world.”

Kraska said once Moore retires “there won't be a lot of people around who helped create the legal architecture for the Law of the Sea.”

He added that Moore quietly continues to lobby for the United States to formally sign on to the historic treaty.

“He has been literally tireless,” Kraska said. “For him, I think it’s really a lifelong mission. I think we'll get there eventually.”

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.