They were trailblazers in law, even when law oppressed their rights.

African American lawyers faced an uphill battle, but over time, helped the country expand civil rights protections and strengthen equality under the law — and are still working hard to spread justice today. We asked community members at the University of Virginia School of Law to write about their legal heroes in honor of Black History Month.

Louis Martinet

Louis Martinet was one of the first Black lawyers in Louisiana. He was a doctor, educator and publisher, but he is probably best remembered as a leading organizer in the fight for equal citizenship after the fall of Reconstruction. Martinet knew that the fight against Jim Crow had to occur both inside and outside the courtroom: He organized confrontational rallies and mass meetings, but also crafted the legal challenge to Louisiana’s Separate Car Act (which tragically ended with defeat in Plessy v. Ferguson). Martinet spent decades fighting tirelessly for racial justice throughout one of America’s darkest periods.

—Thomas Frampton, associate professor of law

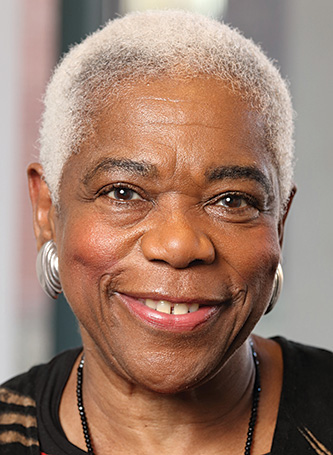

Elaine Jones ’70

Raised in Norfolk during Jim Crow, Elaine Jones decided to challenge societal wrongs at an early age. In 1967, she became the first Black woman to choose UVA Law. By graduation, Jones had turned down a lucrative law firm position to pursue civil rights with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. She was soon representing young Black men on death row in the deep South, and receiving KKK threats. Her 34 years of judicial and legislative advocacy with LDF included challenging inequities in employment, education, voting, housing and criminal justice. In 1993, Jones became the fourth president and director-counsel of LDF, the first woman in that position. In short, Jones is a civil rights hero who dedicated her life to advancing racial justice. Her impact reflects her inner light, courage, optimism and will to make America live up to its promise of universal equality and liberty.

—Kim Forde-Mazrui, Mortimer M. Caplin Professor of Law; director, Center for the Study of Race and Law

Charles Hamilton Houston

While Black lawyers were historically excluded from full participation in the predominantly white American legal profession in the 19th and early 20th century, a young Black Harvard Law graduate, Charles Hamilton Houston, would rise to prominence and influence after joining the Howard Law School faculty in 1923. As the first Black editorial board member of the Harvard Law Review, Houston made quite the impact during his time at Harvard Law School. By the time he graduated with his S.J.D. in 1923, Houston was sold on the importance of formal legal education and he understood that law professors and scholars played a vital role in not just educating lawyers but also developing their understanding of how they might use the law as a tool in civil rights movements. The following year, in 1924, Houston would become the dean of Howard University Law School.

As a legal educator, Charles Hamilton Houston coined the phrase “social engineering,” and this concept would continue beyond Houston’s lifetime to become a legal training principle indoctrinated at the Howard University Law School and the NAACP’s National Legal Committee and the Legal Defense and Educational Fund. Houston’s vision for Howard Law School — one of the premier law schools for Black Americans at the time — was to offer “superior professional training and extraordinary motivation ... to prepare the professional cadres needed to lead successful litigation against racism as practiced by government and sanctioned by law.”

Houston would go on to educate and mentor a generation of Black lawyers, including the first Black U.S. Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall. Because of his legacy, Charles Hamilton Houston has also been fondly crowned “the man who killed Jim Crow.”

—Tiffany Mickel ’22, editor-in-chief, Virginia Law Review

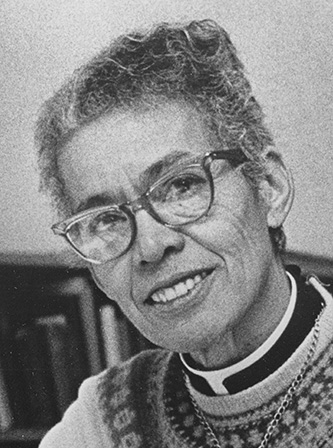

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray (and others)

As the dean of UVA Law, I see more Black legal heroes within our community than I can possibly enumerate here — from “firsts” Gregory Swanson ’51, John Merchant ’58 and Elaine Jones ’70, through the students who founded the Black Law Students Association here 50 years ago, to the pathbreaking judges, lawyers and legal scholars among our alumni, to our current students, who continue to seek justice every day.

Looking beyond UVA, I would highlight the Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray. As a multiracial Black person who wrestled with her sexuality and gender identity throughout her life, Murray lived intersectionality long before Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term. As a trailblazer, Murray broke barriers she faced as a result of both her race and her sex in myriad areas of American society. As a lawyer and seeker of justice, Murray was a participant and leader in numerous movements for equality and human rights for more than half a century. And as a thinker and legal scholar, Murray was an important intellectual architect of modern legal doctrines prohibiting both race and sex discrimination. An unsung hero for far too long, hers is a name that has begun to join lists like this one, where in my view it undeniably belongs.

—Risa Goluboff, dean, Arnold H. Leon Professor of Law, professor of history

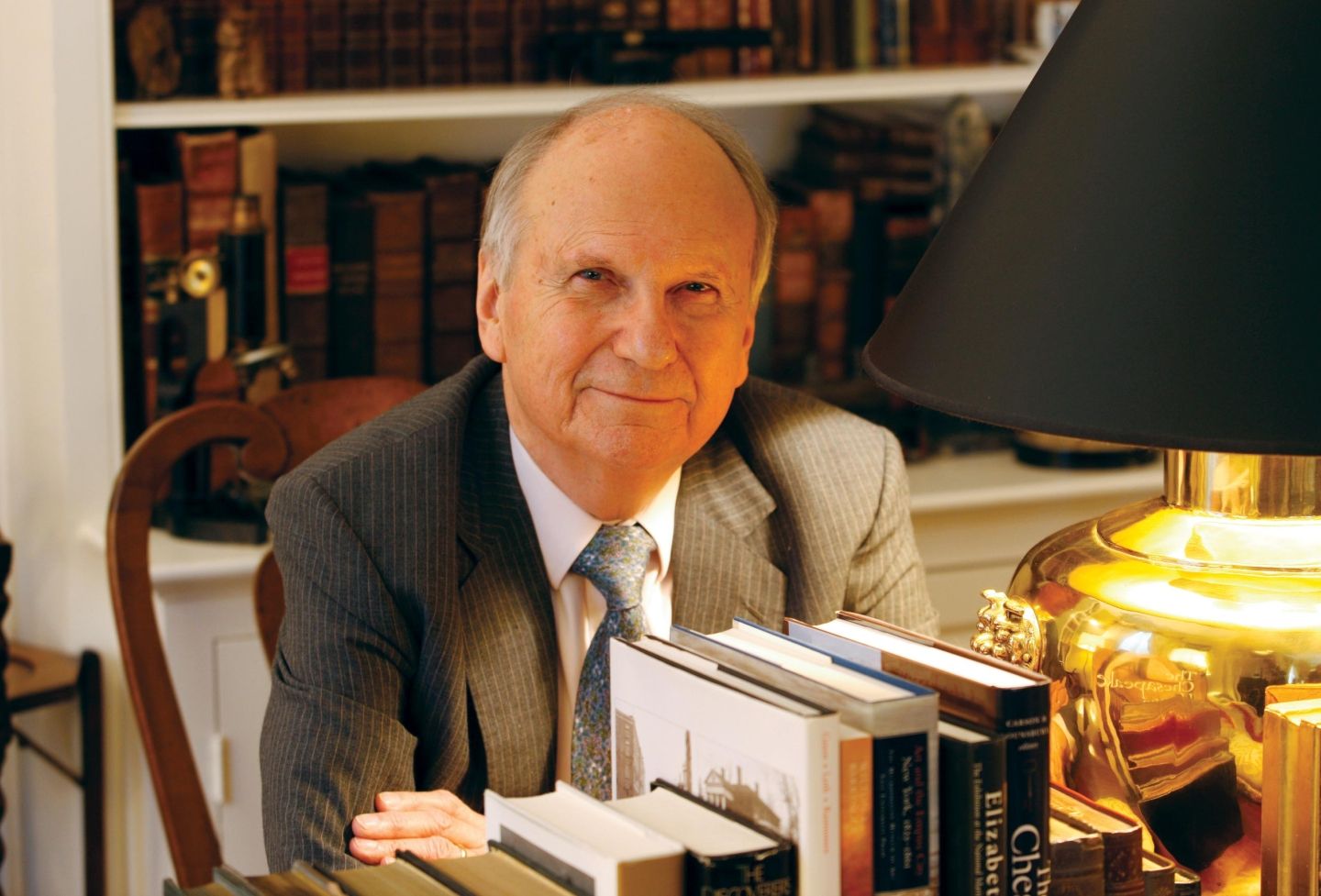

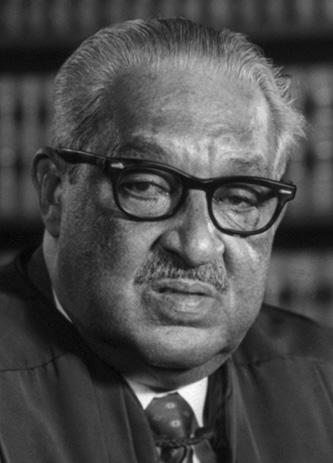

Thurgood Marshall

The late Justice Thurgood Marshall would be on any short list for the most consequential lawyer of the 20th century. His many successes, including his remarkable won-lost record as a Supreme Court advocate before he became a justice, were the result of superb legal skill and strategy. His clients prevailed in Brown v. Board of Education and dozens of other cases because of his and his colleagues’ meticulous planning and carefully crafted arguments. As a justice, he was a key figure in the court’s criminal procedure revolution. Equally remarkable, however, was that the myriad acts of inhumanity he suffered and witnessed never diminished his own humanity. In person, he was charming, funny, and a font of stories and wise observations about the world. He set an example that all lawyers should try to emulate.

—Paul G. Mahoney, a David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law and former UVA Law dean, clerked for Marshall on the U.S. Supreme Court.

Constance Baker Motley

Constance Baker Motley is so admired, three community members recognized her.

Constance Baker Motley, a civil rights movement hero who broke boundaries as the first Black woman to argue a Supreme Court case and to serve on the federal bench, played a crucial role in ending racial segregation. Working for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Motley wrote the initial complaint for Brown v. Board of Education. Several years later, representing the “Little Rock Nine,” her team won a Supreme Court ruling denying the Arkansas School Board the right to delay desegregation. Motley later led litigation integrating Southern universities, most famously helping James Meredith enroll at the University of Mississippi. Despite facing constant danger in the South, she continued to travel throughout Southern states for her litigation efforts, which included defending the Freedom Riders and arguing for Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s right to march in Albany, Georgia, and Birmingham, Alabama. She once stated, “As the first Black and first woman, I am proving in everything I do that Blacks and women are as capable as anyone."

Motley’s legacy echoes in every integrated space in America today.

—Kimberly Jenkins Robinson, Elizabeth D. and Richard A. Merrill Professor of Law; professor of education, Curry School of Education; professor of law, education and public policy, Frank Batten School of Leadership and Public Policy

Constance Baker Motley fought on the forefront for civil rights and broke down many racial and gender barriers in the legal field. As a law clerk for Thurgood Marshall, Motley worked on multiple notable cases, including Brown v. Board of Education. She also worked as a legal strategist during the civil rights movement, serving alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy to help desegregate Southern schools and lunch counters. During the 1950s and 1960s, she argued 10 civil rights cases before the Supreme Court. As Motley turned her attention towards politics, she became the first Black woman elected to the New York senate, the first woman to serve as the president of the Borough of Manhattan, and later the first Black woman to serve as a federal judge when she was appointed to the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Constance Baker Motley played a significant role in civil rights and paved the way for Black women lawyers to come.

—Allison Burns ’22, president, Black Law Students Association

All future litigators dream of arguing in front of the Supreme Court of the United States or of becoming a federal judge. However, these were not possible for Black women until Constance Baker Motley pushed through the long-existing barrier.

Motley operated as an exception to the rule for her entire career. She was the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund’s first female attorney. In her role as associate counsel there, she wrote the original complaint in Brown v. Board of Education. Later on in her career, Motley argued 10 cases in front of the Supreme Court, winning nine.

She continued to rise in her career when she became the first African American federal judge as a judge for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. Judge Motley serves as a personal inspiration and as an inspiration for all Black women lawyers.

—Morgan Palmiter ’22, president, Women of Color

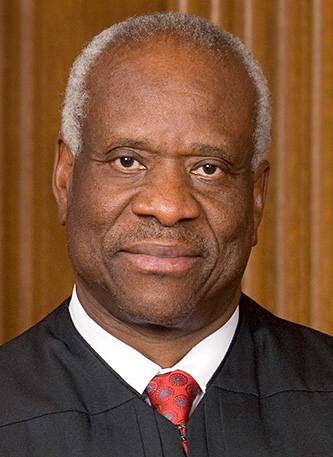

Clarence Thomas

Justice Thomas is brave, brilliant and marches to his own beat. He conscientiously wrestles with his limited, but important, role as a federal judge and then goes about his duties, showing no fear or favor. He is nobody’s man, but instead is his “Grandfather’s Son” [the name of Thomas’ memoir]. When I consider what he overcame, what he stands for, and the influence he has on the court and on America, I am proud to call him my hero.

—Saikrishna Prakash, the James Monroe Distinguished Professor of Law, clerked for Thomas.

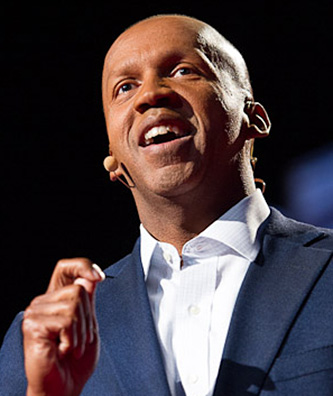

Bryan Stevenson

As the founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, Bryan Stevenson has brought national attention to the enduring problems of racism, mass incarceration, the death penalty and life-in-prison sentences for juveniles. What I respect so much about Stevenson, though, is that he and the attorneys at EJI continue to take case after case on behalf of individual clients while also promoting a robust national discourse on reforming our criminal justice system through his writing, speaking and teaching. [Stevenson is the author of “Just Mercy,” which was recently adapted for film.]

—Annie Kim ’99, assistant dean for public service; director, Program in Law and Public Service; director, Mortimer Caplin Public Service Center

Carlton Reeves ’89

“It’s not about creating new rights. It’s about breathing new life into the Constitution that we have sworn to uphold.” As one of his former law clerks, I can confirm that Judge Carlton W. Reeves lives by these words every single day. From ruling that Mississippi’s ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional in Campaign for Southern Equality v. Bryant, to ultimately granting qualified immunity but meticulously explaining the doctrine’s problematic history in Jamison v. McClendon, it is abundantly clear that Judge Reeves pursues everything through a lens of justice. His commitment to justice is unparalleled. However, I think what I most admire about Judge Reeves is his courage. He is unafraid to do what is right and always speak the truth, regardless of whatever criticisms or consequences might follow. Clerking for Judge Reeves was, and will always be, the honor of my life.

—Aparna Datta ’19 clerked for Reeves in the Southern District of Mississippi, and is now an associate at Williams & Connolly in Washington, D.C.

H. Timothy Lovelace ’06

Lovelace also holds a Ph.D., M.A. and B.A. from UVA.

As a dual degree J.D.-M.A. in history candidate, I had the pleasure of taking Legal History of the Civil Rights Movement with H. Timothy Lovelace, a phenomenal visiting faculty member at UVA Law. In this course, he complicated the “master narrative” of the Civil Rights Movement and exposed the true, often radical calls for change advanced by movement leaders. He introduced us to the known characters and the hidden heroes of the struggle for civil rights, consciously highlighting the women, grassroots advocates and LGBTQ+ Americans whose experiences are often removed from historical accounts. Thanks to his wisdom, thoughtfulness and vision, I now appreciate the nuance of this history and feel better equipped to import these understandings to modern advocacy. In introducing me to countless Black legal heroes, Professor Lovelace became one such hero to me.

—Katharine Janes ’21, president, Student Bar Association

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.