Professor Emeritus W. Laurens “Larry” Walker III, a pioneer in the field of procedural justice and the use of social science in courts who served on the University of Virginia School of Law faculty for 33 years, died Wednesday of natural causes. He was 85.

Known for his kind demeanor, infectious laugh and talent for helping students understand the complexities of civil procedure and litigation, Walker retired as the T. Munford Boyd Professor of Law in 2011.

Early in his career he partnered with two psychologists, former University of North Carolina professor John Thibaut and UVA Law professor John T. Monahan, to produce scholarship that has had a lasting impact on the legal academy, the justice system and beyond. With Thibaut, Walker conducted widely influential empirical research on procedural justice, which explores why fair processes matter in law and across a variety of fields. With Monahan, he wrote the casebook “Social Science in Law,” now in its 10th edition, and developed the first comprehensive system to manage the use of social science in court. Those guidelines shape how expert testimony is conducted in courts around the world today.

“My professional life is linked to these truly great scholars,” Walker said in a story marking his retirement. “We managed to create new corners of interest, one in psychology and one in law.”

Before joining the Virginia faculty, Walker was the Paul B. Eaton Professor of Law at the University of North Carolina. There, he met Thibaut, a social psychologist. After Walker learned of Thibaut’s interest in jurisprudence, they launched a 10-year research program designed to distill fundamental models of legal procedure and examine them through the lens of psychology. The experiments yielded more than 25 articles and ultimately a landmark book, “Procedural Justice: A Psychological Analysis,” published in 1975.

The pair’s experiments used empirical methods to examine the two dominant legal systems: the adversarial legal process used in the United States, United Kingdom and Australia, and the inquisitorial system, where judges lead the process, used in France, Japan, Germany and elsewhere. Among the study’s participants, who role-played the two legal systems, the adversarial system won out. Europeans preferred it even more than those who lived in countries using the adversarial system. The research revealed just how much participants in legal proceedings care about process.

UVA Law professor Greg Mitchell, who holds both a J.D. and Ph.D. in psychology and who co-authored with Walker, said Walker and Thibaut’s work “gave birth to the concept of procedural justice.”

“Procedural justice theory is now one of the most important tools we have for understanding why citizens do, or do not accept, government institutions as legitimate sources of authority,” Mitchell said. “When I was a graduate student in psychology, Larry’s work on procedural justice literally changed the course of my career because it inspired me to change my focus from the study of the executive branch and foreign policy to a study of legal institutions, and to do that I realized that I needed a law degree. Little did I know that years later I would have the honor of teaching with Larry and writing articles with him.”

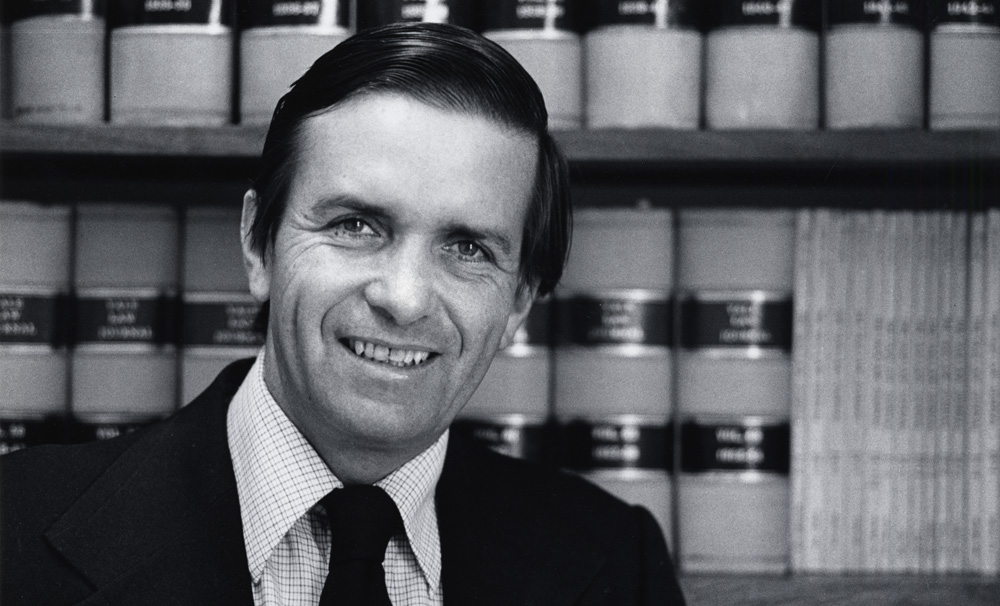

Walker, photographed circa 1978. Law School Foundation/UVA Law Archives

Walker, photographed circa 1978. Law School Foundation/UVA Law Archives

Professor and former Dean John C. Jeffries Jr. ’73 said Walker identified the psychological value of good procedures.

“His insight was that procedures not only guide and constrain substantive decisions, but also help perceptions of fairness by the participants. Larry’s writings spawned a whole school on what is called the ‘dignitary’ value of procedure,” Jeffries said.

The research had implications and an impact beyond the legal system.

“Their research was part of a revolution in social psychology that affected not only thinking about law, but thinking about business and public policy, among other things,” said Professor and then-Dean Paul G. Mahoney in 2011 upon Walker’s retirement.

Walker was also a prolific writing partner with Monahan; together they published 20 articles and developed the concept of social frameworks, which offered a new kind of evidence to courts — expert testimony that provides context by drawing on a body of research.

For example, “It has been demonstrated over and over and over again that eyewitness testimony is quite unreliable,” Walker said in 2011. Witnesses are often mistaken when they identify someone of a different race. As a result, it has become a social framework that defense attorneys regularly use.

Mitchell said Walker and Monahan’s work on the proper uses of social science research in the law “provides the framework that courts and scholars now use to understand the limits and possibilities of social science as a legal tool.”

“For instance, Larry and John explained how evidence sampling techniques can be used to prove damages in mass tort cases where proving individualized damages would prove too costly,” Mitchell said. “This innovation has now been used in multiple cases and is the subject of spirited debate among class action scholars and lawyers. Larry is that rare scholar whose work has had tremendous theoretical and practical influence.”

Christopher Chorba ’01, a former student of Walker’s who is now a partner at the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, said Walker’s scholarship and research “proved to be pivotal in the most significant Supreme Court decision on class actions since the inception of the modern opt-out class action in the 1960s — Dukes v. Wal-Mart.”

In the 2011 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the class-action lawsuit, which involved up to 1.5 million women who sued Wal-Mart for gender discrimination, should not have been certified. The only evidence of discrimination in the case was the testimony of a sociological expert who used social framework analysis — but without studying Wal-Mart’s employment practices through accepted social science research methods. The majority opinion cited an article by Mitchell, Walker and Monahan, who collectively disavowed the expert’s methods in a Virginia Law Review article.

“If you want to cross that bridge [of using social framework analysis], you have to go and study Wal-Mart,” Walker said about the case. “Nobody involved has ever collected any reliable information about what Wal-Mart’s doing. … And it’s not likely to [be studied], because neither side wants to know.”

Walker came from a long line of educators. In 1849, his ancestor, the Rev. Newton Pinckney Walker, founded what is now the South Carolina School for the Deaf and the Blind, and the family continued to lead the school, which later expanded to care for a wider range of children with special needs, for several generations. It was one of the first schools for deaf and blind children in the United States.

After graduating from Spartanburg High School in South Carolina, Walker received a full scholarship to attend Davidson College, where he majored in English and history. He studied at the London School of Economics for a time before turning to a planned career in journalism in his hometown. Earning a full scholarship to Duke Law School, he didn’t initially intend to practice law or become a lawyer. He wanted to be a journalist with a law degree.

But “I decided that after a while I would like to be involved in the decision-making rather than reporting the decision,” he said in 2011.

After graduating law school as a member of the Order of the Coif in 1963, he served as a lieutenant and captain in the U.S. Army, mostly stationed in Würzburg, Germany. Once his service concluded, he joined the Atlanta tax firm Sutherland Asbill & Brennan. Later. he was counsel to another Atlanta firm, Long, Aldridge & Norman.

Though he had a successful practice, he decided to turn to teaching and pursued an S.J.D. at Harvard Law School to prepare, then graduated in 1970. After teaching at UNC for several years, he joined the Virginia faculty in 1978. Two years later, Monahan, who holds a Ph.D. in psychology, joined too, and their partnership began.

“Larry was an ideal colleague and a magnificent friend,” Monahan said, noting the 10 editions of their book together since it was published 40 years ago. “I’ll miss Larry as a colleague enormously. But it’s Larry as a friend I’ll miss even more.”

Walker also advised the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary in the early 1980s in a special counsel role. While serving on the committee, he met and became lifelong friends with Senior Judge Dennis W. Shedd of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. Shedd later became chief counsel and staff director of the committee.

“He had a first rate legal mind, impeccable integrity, a great laugh he shared willingly, and was just fun to be around,” Shedd said. “He never lorded any of his talents over anyone, but was a genuine, well-mannered soul, who always made everyone — even those who disagreed with him — feel worthy and important.”

Shedd added that Walker was so universally respected that the White House wanted to nominate him to a seat on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“Few people may know this because he was so modest about his achievements,” Shedd said. “However, at the time, his academic and research commitments would not allow him to accept the nomination.”

Walker was a member of the Judicial Conference of the Fourth Circuit. In 1988, he was given the Biennial Distinguished Contributions Award from the American Psychology-Law Society for his social scientific studies of the legal process.

In addition to his notable contributions as a scholar, Walker made a significant impact on his students, who praised him for being able to explain the most difficult concepts in the most understandable way.

Chorba recalled that though Walker’s Complex Civil Litigation course was at 8:15 a.m. three days a week, “it was nonetheless the highlight of my semester and law school career.”

“He was serious about his craft, but had a sense of humor when needed, which usually was at 8:15 a.m. on a Friday,” Chorba said. “When it came time to choose a practice at Gibson Dunn some 20 years ago, I wanted to work on class actions because of Professor Walker’s course. I’m now a partner and co-chair the group — and it all started with him.”

Students also turned to Walker for advice even after they graduated. Liz Dougherty ’94, general counsel and corporate secretary for Business Roundtable, took Federal Courts with Walker and recalled visiting him during office hours.

“I asked him to help me understand a thorny procedural issue from one of the texts we were using in the class,” she said. “He gently explained that we weren’t actually supposed to cover that material, and then teased me for decades after about my penchant for ‘touring the backwaters of federal civil procedure.’ Whenever he brought it up, it was accompanied by his wonderful, infectious chuckle.”

William J. Curtin III ’96, now global head of mergers and acquisitions at Hogan Lovells, took Walker’s Civil Procedure course.

“With Southern wit and anecdotal flair, Professor Walker presented the rules, and the cases interpreting the rules, through the lens of his own experience and wisdom in private practice and with the U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee,” Curtin said. “He was particularly beloved for what we came to appreciate as his sequential laugh, which always began with his laughter at a particular circumstance, then followed by a chorus of laughter across the students in his class, and which was then brought to fruition by Professor Walker’s further laughter reflecting his delight at observing the students’ own enjoyment. The rolling laughter reflected a joy of learning, together as a community at Virginia Law, that occurred consistently in Larry Walker’s classroom.

“Over time, many of us students adopted a tradition, whenever we found ourselves passing Professor Walker in the hallway, to take note of, and even to compete for, who among us had become popular enough to be recognized by Professor Walker by name and not only through a kind expression or word of encouragement. Such was the popularity of Professor Walker that we aspired to be known to him personally and to benefit from his authenticity, inside and outside the classroom.”

One of Walker’s best friends is Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III ’72 of the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

“I have never known anyone more universally beloved than Larry Walker,” Wilkinson said. “Kind, warm, unfailingly considerate to others, decent to his very core. Larry was too modest ever to acknowledge his place as a pathbreaking interdisciplinary scholar, but that he was. He and John Monahan showed the way social science could inform the law before many others had even thought of the subject.”

Wilkinson said Walker was the kind of friend who was “calm even during the fourth quarter of a close NFL game” and “took every adverse twist and turn in life in cheerful stride.”

As friends and colleagues sent remembrances, one of the most common refrains was one relayed by Jeffries. Walker, he said, “was a real gentleman.”

Walker is survived by his wife, Sharon Louise Walker; his stepbrother, R. Wiley Bourne Jr. (Elinor); and three children, Margit Walker Nelson (Rob), Helgi C. Walker ’94 (Maldwin); and Carina Smith Severance (Ryan). He also is survived by three grandchildren.

Helgi Walker, a partner at the law firm Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher, said she was often reminded of her father’s impact at the Law School when interviewing UVA Law students for summer associate or associate positions.

“On many an occasion, I could see them looking at the name plate on my desk, the UVA Law School degree hanging on the wall in my office, and then studying my face — I could see the wheels turning. Finally, they would blurt out, ‘You’re not Mr. Walker’s daughter, are you? I loved him!’”

She also reflected on her own time as a student at UVA.

“When I was in law school, I was warmly welcomed into the community, and I realize it was not so much me, but the affection they all had for my father,” she said. “I was very lucky in so many ways.”

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.