|

Behind the Scenes of Brown

E.

Barrett Prettyman, Jr. ’53 Sensed History

in the Making

• Cullen Couch

The Washington monument looms just outside his window. The walls of his office at Hogan & Hartson are festooned with photographs of him with some of the century’s most renowned jurists, authors, and politicians. Soft-spoken, and as articulate as one would expect of a man who has argued 19 cases in front of the U.S. Supreme Court, E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr. ’53, is surrounded by the images of his episodic life.

Born in the District and son of a former Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, Prettyman cut his teeth on the city and its politics. A partner in Hogan & Hartson since 1964, Prettyman also served as Special Assistant to Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy ’51 helping to free the prisoners of the Bay of Pigs invasion, and special Counsel to the House of Representatives during the ABSCAM investigation twenty years later. He also served as the first president of the D.C. Bar, which now numbers almost 80,000 members.

He has chatted with Fidel Castro at Ernest Hemingway’s house in Cuba, teamed with Truman Capote in a documentary critical of the death penalty, and won the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allen Poe award in 1961 for his book Death and the Supreme Court. He represented Ship of Fools novelist Katherine Anne Porter during the last 20 years of her life and, in an act of extreme literary courage, befriended at the same time Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer. As a former president of the PEN/Faulkner Foundation, he calls as friends many of the best writers of our day.

|

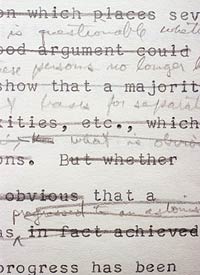

| From the rough draft of a memo Prettyman wrote for Justice Robert H. Jackson, critiquing his concurring opinion in Brown. Neither the memo nor Justice Jackson’s opinion were ever published. Papers of E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr., 1944 (1953-1955)-1982, MSS 86-5, Special Collections, University of Virginia Law Library. |

After graduating from the Law School, Prettyman began his remarkable career as the only person to have clerked for three separate U.S. Supreme Court Justices during a single term: Justice Robert H. Jackson during the reargument of Brown v. Board of Education, then Frankfurter after Jackson ’s death, and Harlan when he replaced Jackson . The Brown case was already in the news, so Prettyman knew before he arrived that he was going to be at the epicenter of the Court’s most important opinion of the 20th century.

Warren Brings a New Dynamic

Fred M. Vinson was still Chief Justice and by all accounts a vote for Plessy. When Vinson died in September 1953 and Earl Warren took his place, Prettyman and his fellow clerks sensed that everything was about to change. “We knew very early on that Warren was a vote to overturn Plessy and we knew that he was going to take on the initial job of drafting the opinion.We did not know how the vote was going to go, but all of a sudden it began to look more as if this was going to be unanimous.”

Prettyman saw how Warren brought new drive and direction to the Court. Though Vinson was a “very likable, easy-going fellow,” Prettyman believes he was not “intellectually among the very top justices” and didn’t have the inclination to lead the Court in any discernible way. By contrast, Warren was “a politician, quite dynamic and forceful, knew everyone’s name in the building, and had a great deal of magnetism about him. He was also tough. He meant business. The atmosphere changed. You had a feeling that things were going to come together now.”

Prettyman watched Thurgood Marshall and John W. Davis present oral arguments. Davis was an “old hand” having argued more cases in the Supreme Court than any lawyer of his day. Marshall used a more informal approach.

|

| PRETTYMAN KNEW BEFORE HE ARRIVED that he was going to be at the epicenter of the Court’s most important opinion of the 20th century. |

“I thought for what Davis was attempting he was really quite good. He stayed away from anything that sounded like racism and put most of his emphasis on state’s rights which he thought would appeal, perhaps not to enough members of the Court, but certainly to some of them. Marshall was folksier and talked in terms of the silliness, if you will, of forcing children apart just to go to school when they would get back together again to play after school. I personally did not think the oral arguments ended up changing much, but for what they were trying to do, I thought they were both good.”

As Michael Klarman describes in his book, From Jim Crow to Civil Rights: The Supreme Court and the Struggle for Racial Equality (see page xx), the case presented Jackson with a dilemma. Jackson believed strongly that judges should shed their own personal views and render decisions based solely on a neutral and thorough analysis of legal authority. But in his reading of precedent and the intent of the framers of the 14th Amendment, Jackson saw that path forcing him in this case to support “Hitler’s creed,” his scornful description of segregation. He had to find a middle way.

“Jackson was concerned that the Court was going to base its opinion strictly on sociology and not on law,” explains Prettyman. “But he pushed sociology aside by finding that African-Americans had made such astounding progress since the Civil War in every area that even if there had been grounds then for separating black children from white children, as a matter of law you could no longer distinguish between them.What Jackson was trying to do was to divine what the framers meant by equal protection in the light of today’s events. He concluded that equal protection meant that you could not, without some basis in fact, distinguish between two separate people and treat them differently solely on the basis of race.”

According to Prettyman, Jackson completed the first draft of his unpublished concurring opinion on December 7, 1953, the day before the second oral argument. Even though Prettyman thought that Jackson wrote it “rather defensively” and found a good deal to criticize in the opinion, “still, Jackson was concurring in overruling Plessy.My own guess is that he knew from the beginning that he was going to go along. To the extent that he was reluctant it wasn’t with the end result, but what he thought the court might do in reaching that result.”

Meanwhile, Prettyman and the other clerks labored on cert petitions and memos and speculated much like the rest of the country on how the Court would decide. Depending on the personality of their justice, some clerks had a clearer view into what was shaping up behind closed doors, but security was very tight. Everyone knew that either way, the result would have a profound impact on the country’s future.

Warren was working on achieving a unanimous decision. Meeting one-on-one with his justices over lunch, during walks, or in his office, he used his political skills to put together a consensus opinion that would bridge the gap between the legal ambiguity and political reality that the case presented. After he had persuaded Justice Reed, the last holdout, Warren knew he had won.

|

| From the map of Spartanburg, SC, that Prettyman created for the Court to use in preparing its “implementation” decision, Brown II. Each blue dot represents one white child; each red dot represents one “negro” child. Papers of E. Barrett Prettyman, Jr., 1944 (1953-1955)-1982, MSS 86-5, Special Collections, University of Virginia Law Library. |

An Opinion Written for the “Man on the Street”

Prettyman was visiting Jackson in the hospital where he was recovering from a heart attack when the Chief Justice arrived with his draft opinion in hand. Prettyman excused himself from the room and went down the hall to wait. After Warren left, Jackson summoned Prettyman back into his room and handed him the opinion to read. “When he asked for my reaction I said I thought it could use a little more law and he did, too. But now I think that is exactly what Warren intended. There was a genius to his opinion. It had a flow to it. Anybody could understand it. Its themes were simple and direct. The man on the street could understand the point. And it didn’t have a lot of the things that Jackson had worried about: that they were going to excoriate the South or the school districts or the district judges. Even though he didn’t agree with the basic theme of it—distinguishing between the races made black children feel inferior— he felt that it was good at accomplishing what it was intended to do, and didn’t do things he was afraid it would do. The opinion was like a speech Warren would give as a governor trying to get across some basic concept to the state legislature. He made it non-controversial, easily understood, persuasive, and avoided areas that might do him in.”

Though Jackson signed on to Warren ’s opinion, Prettyman says that Jackson did not agree with Warren ’s position that the history of the intent of the framers of the 14th Amendment was equivocal. “ Jackson didn’t think it was equivocal at all: he thought it was quite clear that the framers thought that segregation should continue. But Jackson said, in effect, that he couldn’t care less what the framers thought. Jackson was not someone who thought that you had to divine what the various people who had approved the Constitution were thinking. He thought that was absurd. History develops, things change, and the framers obviously never even conceived of most of the things going on in the world in 1954. Therefore, you had to take the Constitution and interpret it as best you could when applying it to today’s events.”

A Nation Waits for the “Big One”

As the Court’s term entered the spring of 1954, reporters and interested observers began to show up every Monday, then the Court’s “opinion day,” to hear the justices render their decisions.With each passing week, the anticipation grew. Finally, on May 17, 1954, the justices convened to read that week’s decisions. In those days, each opinion would go down through a tube to the basement where the reporters were gathered so that they could grab it, read it, and place their calls to their offices. But the Court announced that the last opinion of that day would not go down through the chute, so all the reporters ran upstairs.

| “I WAS OFF TO ONE SIDE, and when [Warren] reached the key point he inserted ‘unanimously’—which was not in the opinion—‘we unanimously hold,’ and the courtroom took in a breath. You could actually hear it because no one had expected that.” |

“The atmosphere was quite extraordinary,” Prettyman recalls. “ Jackson had left the hospital against doctor’s orders to be present and show unanimity. The courtroom was filled because we were getting near the end of the term and everyone was waiting for the big one. The Justices had read a couple of other opinions and made some new admissions. And then the Chief Justice began to read the opinion. I was off to one side, and when he reached the key point he inserted ‘unanimously’—which was not in the opinion—‘we unanimously hold,’ and the courtroom took in a breath. You could actually hear it because no one had expected that. It was very dramatic.”

After the Brown decision came down, Prettyman got a copy of the opinion signed by the court. When the decree implementing the decision came down, he got a copy of that as well. Owning the only two signed copies of both the opinion and the decree, Prettyman could have added a true piece of history to his collection of signed monographs and letters that he keeps at his office. Instead, he graciously donated them to the Law School library where they reside today.

Looking back, Prettyman believed that in the end the Court would overturn Plessy, and the country would be going through dramatic change. “It was unthinkable to many of us in 1954 that the court would rule that you could forcefully separate children into different schools based solely on the color of their skin,” he says. “I personally thought the die was cast as soon as they agreed to take these cases. But there was a sense of history in the making from the beginning, regardless of what the Court did. If they had reaffirmed Plessy, we realized that the country would go one way and if they were going to overrule it, we actually worried about blood in the streets. It was truly that momentous.”