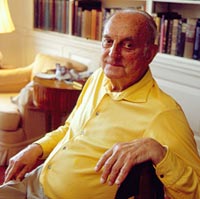

Louis Auchincloss at his home on

Manhattan’s Park Avenue

Louis Auchincloss ’41:

White-Shoe Lawyer, White-Glove Writer

Cullen Couch

POWER AND PRIVILEGE rest comfortably in the moneyed canyons of Park Avenue in New York City. They sit behind leaded glass in spacious apartments and look out over well-swept sidewalks below. They dress in the casual elegance of a lady buying the Sunday Times and they summon to their door groceries delivered by Gristedes. Uniformed doormen guard their polished entrances.

This is the land of novelist Louis Auchincloss ’41. He not only writes about it, he lives it. Once lauded loudly in literary circles as one of America’s greatest living authors, in the tradition of Edith Wharton and Henry James, Auchincloss enjoys quieter, but just as fervid, acclaim these days. A seventh-generation Auchincloss raised in the upper echelons of New York society (his Scottish forebear Hugh Auchincloss emigrated to Manhattan in 1803), he was a partner in the white-shoe Wall Street firm Hawkins, Delafield & Wood specializing in trusts and estates, and retired from the firm at age 70 in 1989.

Auchincloss found literary fame after publishing Pulitzer-candidate novel The Rector of Justin in 1964 (his fame still clings lightly to his slender and erect 87-year-old frame). Like many of the dozens of works of fiction Auchincloss has written (more than 60 works of fiction and non-fiction), The Rector describes the ambience, manners, and ethical quandaries of the Northeastern social elite who once ran this country. In Auchincloss’s eyes, theirs was an exclusive club that wielded power with a potent mix of steely practicality, Protestant righteousness, and cultivated lassitude.

Rejected Novel Leads to Career in Law

Auchincloss began writing when he was a boy at Groton School, and has not stopped since. But he almost did after Scribner’s rejected his first novel while he was a junior at Yale, causing Auchincloss to rethink his whole life plan. He decided he would follow in the footsteps of his father, a successful lawyer.

“Scribner’s rejected it with a very nice letter saying they’d like to see my next book,” he recalls with amusement. “You would think that a 20-year-old might be satisfied with that, but I was not. I was crushed. This was my Madame Bovary, so to speak. I told my father that I must give up all ideas of writing and go right away and be a lawyer. The University of Virginia was the best law school who would take me on the basis of three years [of undergraduate work]; I was actually a Phi Beta Kappa. Father said, ‘well, you’ll spend the rest of your life explaining why you don’t have a Yale degree,’ and, of course, he was right. My father was very dear—a very good lawyer and perfectly charming. He said, ‘Well, we’ll see it your way.’ So down I went to Virginia.”

One can only imagine the cultural, if not social, differences this died-in-the-wool Manhattanite faced moving from the urbanity of New York City to the cloistered hamlet of Charlottesville in the 1940s. His white-glove manners, elegant diction, and reverence for tradition melded well with the cavalier gentility of the Law School’s social and intellectual milieu. As a man who tells a wonderful story, and tosses off bon mots like John Rockefeller did his dimes, he gathered to his side many hearty companions.

“I was very happy in Charlottesville,” he says. “I liked the Law School and all my friends immensely, and I liked being on the Law Review. There were a lot Northern guys down there, you see, young, rich, married ones. They all had nice houses and they were all very good friends of mine. I was a constant bachelor at their houses.”

Auchincloss didn’t write during his first year at the Law School; he found that his studies required exacting work and the rejection from Scribner’s still rankled. But not for long. As bits of time became available, so too did a realization. “I liked the Law School. I loved Virginia and I loved the University. When I stumbled into Cardozo’s opinions, I became fascinated by his style and realized that the two occupations, law and writing, are more or less synchronized. I began the two careers I would follow from then on, law and writing. That summer I started a novel; the second summer I finished it.”

Auchincloss began his third novel, Indifferent Children, in the last year of World War II and finished it in 1947. He published it under a pen name, Andrew Lee, at the request of his mother. He never did that again. “You would think that a person who was 29 years old and had seen four years’ sea duty in the Navy in the Atlantic, Pacific, and the Caribbean would have had enough guts to resist his mother, but I didn’t. She was a very powerful woman, enormously able. She thought this novel was trash and would hurt me in my legal career. She persuaded me to use a pen name, which, of course, was pretty ridiculous. It took her a number of years to come around, but she finally did.”

Juggling Careers

As the lawyer’s fundamental tool, writing lends itself to applications beyond the legal field and, as professions go, likely inspires more of its members to be novelists than any other. But in Auchincloss’s case, he found the profession actually hindered his writing career, not because of any of the obvious stylistic or other differences between fiction and legal writing, but because of appearances.

“When I was a young lawyer at Sullivan & Cromwell, I did it under the counter until the book was published, and then it was a cause of considerable talk. John Foster Dulles, who was then the managing partner, said to someone at a party after they joshed him about running a sweatshop down there at 40th & Wall Street, ‘On the contrary, I understand the clerks all write novels.’”

While Auchincloss was a good lawyer and enjoyed the craft, his fiction writing was his primary interest. “I used to go to all the Saturday night parties with the other young lawyers. They talked all the time about whether they were going to be a partner; I thought here was a whole room of my friends who were all terrified they might not be partners; I was terrified I might be one.”

At that point, Auchincloss decided he was going to quit the law and write full time. “Father said, ‘Well, who’s going to support you?’ I said, ‘Well, you are!’ He said, ‘I guess I am,’ and he did. But after two and a half years, I decided that I’d better make some money. I also didn’t need that much time to write.

“For some years, it went quite well. The clients all thought that I was fine. It was quite well known that I was a bestseller; they thought it was rather nice to have somebody working on their things who was also a novelist. They didn’t know that I really did much of the work of the partners. Then when I was in charge and they realized I really was doing all the work, right away a lot of clients didn’t like the idea of a novelist being their lawyer.”

The Lawyer Retires; The Writer Continues

It’s hard to square Auchincloss’s astonishing output with the fact that all the while he practiced full time and served as chairman of the board of the Museum of the City of New York and president of the Academy of Arts and Letters, among other civic duties. For a man who could write three legal-pad pages of fiction every day while juggling those duties, being freed from them would seem to open up a veritable floodgate of prose. And it has. Auchincloss feels that he is at the top of his game right now.

“I think I’m writing better. My last book [East Side Story published in 2004] is generally considered by my critics to be the best thing I’ve done, so maybe there was some….” His voice trails off as he thinks about how his career may have been different after all. “Well, who knows? Anyway, I needed that money. For a long time I made quite a bit and I had a family to raise.”

Two of his sons, John ’83 and Andrew ’89, followed their father’s lead and graduated from the Law School. They now practice law in Connecticut and New York. His late wife, Adele, an artist who was active in preserving New York parkland, died in 1991.

Auchincloss continues to supply a loyal following with a stream of novels and short story collections. In fact, he sent his latest novel to his publisher in July. Aging is often unkind, but it appears to give Auchincloss even more energy.

“I have the whole day,” he says. “I’m writing so much that I may have to change publishers. I have a book coming out in the spring. I have another book already submitted and the publishers won’t do that for a year from now. I completely understand their point of view and they completely understand mine. I said I’d like to be around when my books come out. I’ve reached an age where you can’t be sure of that.” He pauses. “Not that you ever can, really.”