Penumbras and emanations, brawlers and vagabonds

In researching her book on vagrancy law, Risa Goluboff, John Allan Love Professor of Law and Justice Thurgood Marshall Distinguished Professor of Law, came across a revealing artifact in the substantive due process debate in the mid-20th century U.S. Supreme Court.

Vagrancy laws, exported to the colonies from Elizabethan England, addressed the problem of “poor people, wanderers, common drunks and prostitutes, brawlers, rogues, vagabonds or anybody who didn’t fit in,” she says. Over time, local governments began using them to target religious and racial minorities, political dissidents, and cultural non-conformists. Beginning in the 1950s, social reform movements started challenging these laws.

It took the Court over two decades to figure out whether and why the laws were unconstitutional. It was a particularly important issue for Justices Black and Douglas. The Lochner era version of substantive due process still loomed large in their rearview mirror and the two New Deal liberal justices, both Roosevelt appointees, were not about to let it return. “They hated economic substantive due process and the idea of fundamental rights,” Goluboff says. “They fought against it from the ’30s to the early ’60s.”

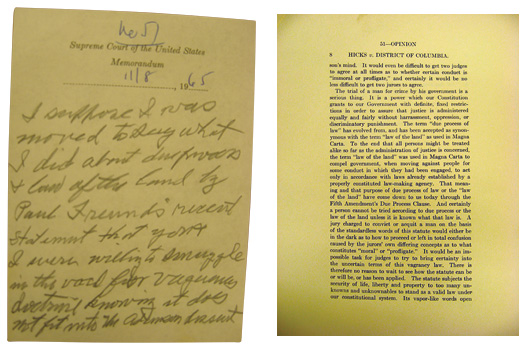

The note from Black to Douglas comes from Court deliberations in Hicks v. District of Columbia, a 1966 vagrancy case about a street musician in DuPont Circle in Washington, D.C. Black had written a majority opinion originally describing due process as the same thing as Magna Carta’s law of the land. Douglas had asked him why he was using that language, and Black replied:

“I suppose I was moved to say what I did about due process and law of the land by Paul Freund’s recent statement that you and I were willing to smuggle in the void for vagueness doctrine knowing it does not fit into the Adamson dissent.”

Black’s dissent in Adamson (joined by Douglas) from 1947 said the Court should incorporate only those rights specifically enumerated in the text of the Bill of Rights. “Apparently Freund accused them of playing fast and loose with substantive rights in conflict with what they had said in Adamson,” says Goluboff. “I think Black was trying to tether the due process clause very closely to its historical procedural protections grounded in Magna Carta so that he could draw quite tight boundaries, a very stark line, between what was procedural and what was substantive.”

Black and Douglas would ultimately part ways over how strictly to interpret the text of the Constitution, and especially the Bill of Rights. This exchange over Hicks reflects one moment in their increasingly separate paths. Douglas found more constitutional room in the words of the document for the “penumbra and emanations” he articulated in Griswold—the contraceptive case—in 1965, and still more space for full substantive due process in the 1973 Roe decision.