|

Truth, Wherever It May Lead

Five

Decades of Studying the Middle East: R.K. Ramazani S.J.D. ’54

Cullen Couch

Imagine attending a law school so factionalized that thugs steal and destroy the ballot boxes used in a school election. Later, they stab to death the dean on the front steps of the school, invade one of your classes, slaughter a classmate, and then rush out into the hallway chanting your name — the next target.

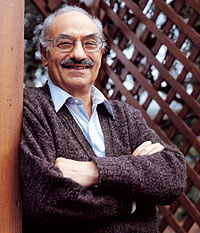

Such was the School of Law at the University of Tehran in 1952, the alma mater of Professor R.K. “Ruhi” Ramazani S.J.D. ’54. Now living quietly with his wife, Nesta, in their beautifully landscaped home in Ivy, Virginia, Ramazani’s soft voice and courtly manner seem at odds with his history as a young Iranian law student leading a political faction in a strife-torn country.

Fearing for his life, Ramazani left the blood-spattered walls of that classroom and slipped away to safety by chanting “Get Ramazani …” along with the thugs in the hall. Fortunately, he finished his law degree and began to seek the personal and intellectual safety of an academic career in the United States.

During Iran’s oil nationalization crisis in the early 1950s, turbulence swept through the country, especially in universities, where the rhetoric turned into a potent brew of violence and extremism. As one of the campus activists supporting the liberal/nationalist faction, Ramazani attracted the attention of the vicious Tudeh, the local communist party. They had ordered the campus murders and Ramazani was on their list of intended victims.

“There was nothing to protect you,” he recalls, “and no way to have an ambition to become a lawyer or teacher on your own merit. It was a question of what faction you sided with. I couldn’t practice or teach law while living under the threat of arrest and imprisonment for political reasons, so I looked to America as a place free from those threats.” A year after he arrived in the United States a CIA-sponsored coup ousted the popularly-elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadeq and reinstalled the Shah. All hope for democracy was ended.

| “WHEN THERE IS NEED to be pragmatic, Iranians are pragmatic and that is something the United States must understand.” |

Ramazani’s academic career in the United States began at the University of Georgia where he studied American constitutional law and international law under Professors Albert Saye and Sigmund Cohn. Both professors felt that Ramazani’s career would benefit if he continued his studies at the University of Virginia Law School. Granted a DuPont scholarship, Ramazani pursued his S.J.D. under the primary guidance of Professor Hardy Cross Dillard and with the close support of Professor Neil H. Alford.

“I loved the man,” says Ramazani of Dillard, who later became dean of the Law School and created the school’s early curriculum on international law. He later became a judge on the International Court of Justice. “He had such an extraordinary humane touch. We were really close. He was fatherly with me, compassionate, understanding, a true mentor. He was very broad-minded and of proverbial eloquence. He was a magnificent writer. When he wrote an essay, it was absolutely superb.” Ramazani’s fondness for Dillard caused him to dedicate one of his books to his memory.

In June 1954, shortly before he completed his doctorate, Ramazani taught his first course — Middle Eastern politics — beginning a successful lifelong career teaching at the University of Virginia’s Woodrow Wilson School (later Department) of Foreign Affairs. Coming from the violence of his undergraduate years in Tehran, he developed an intense passion for the democratic ideals of Thomas Jefferson, and the collegial gentility of his University. In his teaching syllabus, Ramazani often quoted Jefferson’s mission for the University: “Here we are not afraid to follow truth, wherever it may lead, nor tolerate any error so long as reason is left free to combat it.” Ramazani has been studying Middle Eastern affairs and diplomacy for the better part of five decades, publishing ten books and more than 100 articles. He is known worldwide as an expert on the region. Ramazani cites his legal education for providing the intellectual framework for his original theories about international politics and the foreign policy of small countries. “The study of law gave me an advantage; it provided intellectual discipline.”

That discipline led Ramazani to look at international relations from a variety of perspectives. In foreign policy scholarship, Ramazani found that theorists often focus on narrow slices of an event, usually corresponding to their chosen field, and miss the interactions amongst other elements that tell a broader story. Instead, Ramazani navigates the interstices of disciplines to find more revealing angles.

For example, some scholars see Iran’s Islamic revolution as the result of a rejection of American domination, while others cite the country’s internal power struggles over religion. Ramazani argues that it was neither, but rather a question of how the Shah unsuccessfully juggled his relationship with the United States and the Shah’s own internal constituencies. Whatever the cause, the events of that time still resonate. Today, the United States government considers Iran part of the “axis of evil,” while the mullahs in the Iranian government see America as the “great Satan.” While the parallel construction of these international epithets raises interesting questions, they describe a tone of mutual suspicion and soaring rhetoric that has lasted decades.

Today, the invective has become truly radioactive as Iran pursues a nuclear energy program in the face of American suspicion of Iran’s pursuit of nuclear weapons, but Ramazani is more sanguine about Iran’s intentions. He believes that Iran intends to use nuclear power to generate electricity so that the country can sell its oil instead of having to use it domestically, a reason not often heard in the mainstream U.S. media. While he concedes that a weapons program is a possibility, “when there is need to be pragmatic, Iranians are pragmatic and that is something the United States must understand. I have tried to show in my work that there has always been this tension between religious ideology and pragmatism in Iran, all the way back to Cyrus the Great.”

And Ramazani believes that ultimately pragmatism will win out given the large reform movement now stirring in Iran. “A recent poll showed that an overwhelming majority of Iranians want relations with the U.S. What is happening at the grass roots is unstoppable. The diehards can put someone in jail, arrest others, but in the mid-term they cannot succeed. An overwhelming number of people support reform and a more secular society and government.”

Does he miss the land of his birth? “Politically, no. But it still has beauty in its culture and literature. Iran is very unique in its contribution to literature and art and philosophy, and I think it is pitifully misunderstood because of the revolution and the hostage situation. I last visited in 2000 and found an enormous sense of hospitality, importance of personal relations, family ties, courtesy, and consideration for others. There are some really ancient values there.”

Over the years, Ramazani has consulted on Middle Eastern affairs with the United Nations and various departments of the United States government including State, Defense, and Treasury. His counsel has been sought at the highest levels, most notably by President Carter during the Iranian hostage crisis. From that broad experience in American foreign affairs, Ramazani sees a “sea change” in the course of American policy since the terror attacks of 9/11.

As a result, he says he “has never known such deep and widespread anti-American sentiment. As a person who has seen both sides, tried to converse with both sides, it’s clear that America now comes across as a menace, a threat to these societies. There are millions in the Middle East who aspire to democratic ideals, but American behavior no longer comes across as the promise of freedom for the young or for democratic elements because America has made the military — not the Fulbright program, not the Peace Corps program, and not education — its principle instrument of foreign policy.”

Last fall, he told members of the Law School’s Business Advisory Council that given the historical record and cultural reality of the Middle East, it should have been no surprise that the Bush administration’s “unrealistic assumptions” would turn out so wrong, and that press reports, official accounts, and scholarly and academic writings on the conflict reveal no clear reason why the administration chose to invade in the first place (Text of the speech).

As a scholar, Ramazani seeks the truth, but the truth can be troubling for a naturalized American citizen who found peace and freedom in a country now vilified in large portions of the world. “The best decision of my life at a young age was to come to America. The reality of America is in the air I breathe. I know there are critics, but I believe that America is unique as a land of opportunity; unique in its freedom of the press and religion. This is truly a multicultural country, a melting pot if you wish. For some people it’s not what it used to be, but it still is for me. When I return from traveling and get off the plane I want to kiss the ground at Charlottesville airport.”