Mueller was featured in UVA Lawyer in 2002. Photo by Tom Cogill

5 in Criminal Law

6. Robert Mueller ’73

Directing the FBI, Russia Investigation

With more than three dozen indictments or pleas, Robert Mueller ’73 has changed the world as special counsel looking into Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election.

Mueller’s work as special counsel is part of a long, impactful career as a public servant.

With his service as director of the FBI following the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Mueller converted the bureau from a mostly after-the-fact, crime-solving organization to one focused on threat prevention. He oversaw a reorganization of the bureau that involved the retraining of existing agents, and the massive hiring of new ones — all the while improving coordination with outside law enforcement agencies and the intelligence community.

His tenure was also noted for opposing the George W. Bush administration’s “Stellar Wind” domestic surveillance program.

Prior to leading the FBI, Mueller led the Justice Department’s Criminal Division, overseeing investigations into the terrorist attack on Pan Am Flight 103, and the criminal activities of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega and crime boss John Gotti, among other cases.

7. Roscoe C. Howard Jr. ’77

7. Roscoe C. Howard Jr. ’77

U.S. Attorney, Compliance for ZTE

Roscoe Howard ’77 tried more than 100 cases as a federal prosecutor. He served as the U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia from 2001 until 2004, and oversaw the investigation into the 2001 anthrax mailings.

He currently serves as compliance coordinator for the settlement between the Department of Commerce and ZTE, the Chinese multinational telecommunications equipment company that pled guilty to illegally exporting U.S. technology to North Korea and Iran.

He is a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of Barnes & Thornburg.

8. John Gleeson ’80

Making Charges Stick Against the ‘Teflon Don’

It took some trial and error, but John Gleeson ’80 learned from past mistakes to win the 1992 conviction of mob boss John Gotti, who remained in prison until his death.

Despite living in a modest Queens home and claiming to be a salesman, Gotti was actually head of the powerful Gambino crime family, which controlled underground gambling, narcotics and loan-sharking industries from New York.

“Since taking over an empire that experts estimate grosses at least $500 million yearly from illegal enterprises, Gotti has become organized crime’s most significant symbol of resistance to law-enforcement since Al Capone cavorted in Chicago 60 years ago,” opined the New York Times Magazine in 1989.

Gotti’s reign as crime boss began in 1985, the same year Gleeson, today a law firm partner and retired federal district judge, became assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of New York.

Previous prosecutions, which included witness intimidation and jury tampering, had resulted in high-profile acquittals for Gotti. Gleeson himself had been co-counsel on a 1987 federal racketeering case that failed to stick against the so-called “Teflon Don.”

But this time would be different.

Gleeson, U.S. Attorney Andrew J. Maloney, and the other lawyers and law enforcement on the case took a pragmatic approach. They kept the case as simple as possible — and went for the head, Gotti.

Incriminating wiretap recordings persuaded Gotti’s right-hand man, “Sammy the Bull” Gravano, to flip and provide testimony against his boss. Signing off on the strategy was then-U.S. Assistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division Robert Mueller ’73.

The prosecution then convinced Judge I. Leo Glasser to sequester the jury and keep them anonymous. The team also convinced Glasser to disqualify three lawyers and multiple witnesses Gotti hoped would aid his defense.

In court, the prosecution presented only the strongest six hours of surveillance recordings from 18 months of FBI field work.

As co-counsel with Maloney, the unassuming Gleeson, then 38, questioned most of the witnesses during the trial and “served as the courtroom point man,” The New York Times reported upon the trial’s outcome.

“Mr. Gleeson … presented the evidence with a calm professorial air, ignoring Mr. Gotti’s arm-swinging bravado and violent glares. Mr. Gleeson’s boyish appearance, the dark wavy hair, the horn-rimmed glasses and earnest voice, seemed to enhance the sincere image — a James Stewart character, perhaps, upholding truth against the mob.”

Gotti was convicted of five murders, conspiracy to commit murder, racketeering, obstruction of justice, tax evasion, illegal gambling, extortion and loan-sharking.

When asked how it felt to get his man, Gleeson modestly deflected, “I didn’t get John Gotti.” But the outcome spoke to the contrary.

Gleeson received the Thomas Jefferson Foundation Medal in Law in 2016 for his career’s work.

9. Joyce White Vance ’85

9. Joyce White Vance ’85

First Material Support of Terrorism Case

As U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama from 2009-17, Joyce White Vance ’85 was the first to charge a material support of terrorism case in the district and prosecuted the first cybercrime cases there, established a civil rights enforcement unit in the office, and aggressively prosecuted heroin traffickers and cases of fraud and public corruption.

Prior to the appointment, she was chief of the Appellate Division, and before that, worked in the Criminal Division. Early in her career, she investigated Eric Robert Rudolph, who bombed a Birmingham abortion clinic, killed a police officer and set off a string of church fires — he was also Atlanta’s “Olympic Park Bomber” — and successfully prosecuted five police officers charged with conspiracy to violate civil rights.

10. Deirdre Enright ’92 and the Innocence Project

For Over a Decade, Freeing the Falsely Convicted

Emerson Stevens and Darnell Phillips would say the Innocence Project at UVA Law changed the world.

So would Messiah Johnson, Bennet Barbour, Edgar Coker, Gary Bush and others.

These ex-prisoners, falsely convicted of serious crimes such as rape and murder, are all free because of the work the project has done over the past decade to demonstrate their innocence.

Stevens was convicted of the 1985 abduction and murder of Mary Keyser Harding, a Lancaster, Virginia, mother of two. His sentence was set at 164 years.

Phillips was convicted of the 1990 rape of a child in Virginia Beach, Virginia, and sentenced to 100 years in prison.

Phillips walked out of prison in September 2018 and Stevens in May 2017. In both cases, clinic directors Deirdre Enright ’92, who founded the project at UVA Law, and Jennifer Givens were on hand to greet their clients.

Stevens, shortly after being released, donned a shirt that read, “Sorry, I can’t hear you over the sound of my freedom.”

Phillips raised his hands to the sky and felt the rain.

The Innocence Project Clinic is the main forum for the project’s efforts. The for-credit class gives students practical experience investigating and litigating wrongful convictions in Virginia. These days, the for-credit clinic operates alongside a separate, extracurricular student pro bono clinic.

Enright and Givens said much of their time is spent following a thread that may take years to unravel.

Sometimes it’s connections that pay off, as in the Stevens case. The evidence didn’t add up and the project had serious questions about how the investigation was conducted. They knew documents existed that could shed light on their concerns and, perhaps, turn the case.

“We went through three commonwealth’s attorneys and two sheriffs before we found those files,” Enright said. “It was only because the new sheriff called us when someone on his staff found a box in the room for incinerating and brought it to his attention that we got the files.”

Givens added, “Deirdre had spent years in Lancaster County developing a relationship with that office. The scary thing is, it so easily might not have happened.”

Other discoveries involve greater happenstance. In the case of Phillips, the prosecutor told Phillips and the trial court that the physical evidence in the case had been destroyed. But Givens randomly learned that might not be the case while speaking on the phone with a Virginia Beach court clerk in 2015.

“She said, ‘We have a bag of stuff here,’” Givens said. “Nobody had ever said that before.”

Givens and two students drove to the courthouse evidence room and discovered that a rape kit and garments from the original investigation indeed had been in storage, but had never been tested.

The directors said finds like these don’t mean the battle has been won. It’s usually just a start.

In Phillips’ case, after two labs failed to come up with anything conclusive from the time-denigrated samples, a third lab in California found evidence during the summer of 2017 that at least two men had touched the garments, and neither man was Phillips.

Enright followed up on the new evidence by flying to see the victim, now an adult, who said in a sworn affidavit that police used deception to convince her to name Phillips as her attacker. They told her that Phillips had assaulted other children, that his alibi did not check out and that her blood was found on his underwear at his home — none of which was true.

Her statement turned out to be what was most persuasive to Virginia’s parole board, the directors said.

While both Phillips and Stevens have been freed by the board, neither have been fully exonerated, and the project continues to represent them.

Dennis Barrett ’09, an attorney with Schaner & Lubitz who was a member of the original Innocence Project Clinic and the first student to work on Phillips’ case, said the clinic has had a meaningful impact for both the clients and the students.

“Most importantly, the clinic has helped free a man that has been unjustly imprisoned for nearly three decades, but I also know the clinic has had an indelible impact on those students fortunate enough to work on it,” Barrett said. “Few of us will end up with a job working on wrongful convictions full time, but none of those who have worked at the Innocence Project will leave the experience without a profoundly different view of the justice system that we’ll carry forward in our personal and professional lives.”

The effort got its start at the urging of now-UVA President Jim Ryan ’92, then vice dean, in coordination with then-Dean John C. Jeffries ’73.

The clinic expects to add a third attorney this year thanks to the generosity of a matching fundraising campaign instigated by Jason Flom, a founding board member of the national Innocence Project.

5 Government Servants

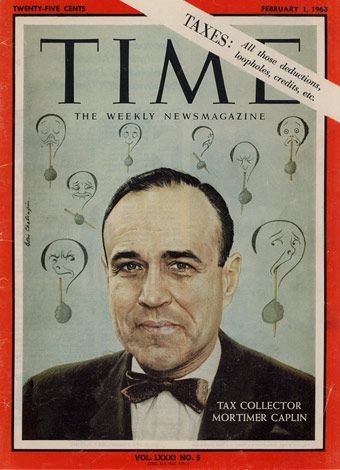

11. Mortimer Caplin ’40

Friendlier Tax Collection

A centenarian and the first Jewish law professor at the University of Virginia, Mortimer Caplin ’40 served as IRS commissioner from 1961-64. His tenure is remembered as ushering in a kinder, friendlier approach to tax collection. He sent along a note to taxpayers, in his own name, appealing to their sense of citizenship and patriotism, stating “taxes are necessary for the kind of orderly government which will preserve America and its way of life.” He also was the first commissioner to utilize computing to process the vast amount of incoming data.

He later founded Caplin & Drysdale, one of the nation’s leading tax law firms, with Doug Drysdale ’53.

Before his career in government and as a professor, Caplin served as U.S. Navy beachmaster during the Normandy Invasion in World War II, and was cited as a member of the initial landing force on Omaha Beach.

12. Fred Fielding ’64

12. Fred Fielding ’64

White House Counsel

Fred Fielding ’64 served as White House counsel to Presidents Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush. He was associate White House counsel under President Richard Nixon — and falsely rumored to be “Deep Throat,” The Washington Post’s unnamed source in the Watergate scandal. Most recently, he was counsel to President Donald Trump’s transition team.

13. Edwin Lane Kneedler ’74

13. Edwin Lane Kneedler ’74

Supreme Court Argument Ace

An employee of the Justice Department since 1975, Deputy U.S. Solicitor General Edwin Lane Kneedler ’74 has argued more cases at the U.S. Supreme Court than any other practicing lawyer.

“The biggest case he participated in, he said, would be the defense of [President Barack] Obama’s Affordable Care Act, which the court mostly upheld on a 5-4 opinion by [Chief Justice John] Roberts,” The Washington Post reported in 2014. “Which is not the same as saying Kneedler favored the act. Both Republicans and Democrats who have worked with Kneedler say they have no idea about his political leanings.”

14. Luis Fortuño ’85

14. Luis Fortuño ’85

Governor of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico

As 10th governor of the commonwealth of Puerto Rico, from 2009-13, Luis Fortuño ’85 helped the U.S. territory implement major reforms. Its bond rating increased twice and, from 2011- 12, Puerto Rico experienced economic growth for the first time in the previous six years.

15. Emily Webster Murphy ’01

15. Emily Webster Murphy ’01

GSA Administrator

With decades of experience in government contracting and procurement, Emily Webster Murphy ’01 currently serves as administrator of the General Services Administration, where she is responsible for annual contracts totaling $54 billion and leads a workforce of 11,600 full-time employees.

More Change Agents

- 100 Change Agents: A Completely Incomplete List of UVA Lawyers Who Changed the World

- 5 Who Fought for Rights

- 5 in International Law, 5 Military Leaders

- 5 Virginia Voices

- 5 Business Leaders, 5 General Counsel, 5 in Investing, 5 in Law Firms

- 5 Nonprofit Leaders, 5 Educational Leaders

- 5 Who Were There To Make a Difference

- 5 Best-Selling Authors

- 5 in Sports, 5 in Entertainment

- 5 in a League of Their Own

- 5 From the Early Days, 5 Firsts

- 5 Who Changed UVA