Not long after graduation, Pat Vaughan ’68 traded a sport coat for a flak jacket, a seat in the law school classroom for one in the back of a Bell UH-1 “Huey” beating a path toward hostile fire.

Vaughan provided legal support to the U.S. Army’s 11th Armored Calvary Regiment from 1969-70, trying special courts martial involving drug charges, insubordination and refusal to go to the field, as well as more routine legal matters, such as absence without leave.

The duty required him to personally deliver paperwork — often divorces for soldiers who had received “Dear John” letters — directly to the fire bases. He had his own personal Huey, one that would shuttle him from his office to regimental command.

“Going to Vietnam was not one of my life goals,” Vaughan said. “Surviving it became one.”

Vaughan joined 1968 classmates Weaver Gaines, Jack Hannon, Stuart Johnson, Ed Levin, Dave Scull, Bob Wright and Don Zachary, who shared their experiences for the May 12 panel discussion titled “The Lasting Impact of the Vietnam War.”

Attended by dozens of classmates and their families, as well as some members of other reunion classes, the presentation was part of Alumni Weekend events. The panel helped mark 50 years since the Class of 1968’s graduation — the year graduate deferments ended and the Tet Offensive occurred.

The United States, allied with the Republic of South Vietnam and coalition of other countries, launched hundreds of attacks on the Viet Cong and North Vietnamese armies during the three years leading up to 1968. In January, the enemy responded with it famous offensive, which resulted in the capture of Hue, the imperial capital of Vietnam, and enemy forces reaching the grounds of the U.S. embassy in Saigon (though never taking the building itself).

That year saw some of the war’s bloodiest fighting, with 543 Americans dying in seven days in February, and the U.S. massacre of Vietnamese civilians at My Lai in March. The shocking developments were a turning point in American support for the war.

With the anniversary of Tet, and the acclaimed PBS docuseries “The Vietnam War” debuting not long before their reunion, the time seemed right to reflect.

Panelists told of their service (or successful avoidance thereof ), spoke of disruptions in their lives due to the draft and lamented the war’s dismal outcomes.

The Disc Jockey Who Didn't Miss a Beat

<div>

Pat Vaughan, second from left, stands in front of the legal office for the 11th Armored Calvary Regiment, along with other members of the legal team. <em>Courtesy Pat Vaughan</em></div>

By Pat Vaughan ’68

Editor's note: The following is a shortened version of a longer first-person account Vaughan read during the panel.

After my training period, I would take the [legal] paperwork up to the regimental commander up at the front. This happened on a weekly basis. I had my own personal Huey.

Picture this: Cigar-chewing, shirtless door gunners with their flak jackets hanging askew.

Most of the trips were routine. A few were harrowing.

Our forward unit was located at Quan Loi, near the Parrot’s Beak, a point in Cambodia dipping into Vietnam. The Ho Chi Minh Trail and the Vietcong were just to our north. Our Quan Loi office was an old box truck. While at the front, I generally ate and slept with the enlisted men underground.

The officers’ mess was located in a French plantation house. On the third floor there was a disc jockey — à la Adrian Cronauer [the inspiration for “Good Morning, Vietnam”] — playing to the troops in the field around the camp on WACR, Radio Blackhorse.

The Vietcong would triangulate on the radio signal, attempting to make effective strikes on the base. One night they were successful. And all of the troops in the field knew immediately when they heard over the radio, “Red alert! Red alert! And that’s no sh--, because a round just went through my No. 2 turntable!

“Next, I’ll play a little Santana, with‘Evil Ways’…”

Fortunately for the DJ, the round had a delayed fuse and exploded right in the belly of the house. Also fortunately, the brass had eaten earlier that day.

Hannon was a Navy air intelligence officer before law school. He was assigned to an air wing on the attack carrier USS Hancock when the war began to ramp up, in 1965.

“We were on station 75 miles off of Da Nang in the northern part of South Vietnam when President [Lyndon] Johnson made his ill-fated decision that we were going all-in,” Hannon said. “And within the next 48 hours, we were getting targets assigned from much higher authority. We were briefing pilots and sending them off into harm’s way.”

Lacking modern-day precision-guided weapons, planes had to dive relatively close to their targets.

“The North Vietnamese were ready for us,” he said of the numerous U.S. casualties and damages.

Weaver Gaines served in Long Binh, Vietnam, where he handled special courts martial as a non-JAG lawyer for the Army. Courtesy Weaver Gaines

Wright, who would go on to become president and CEO of NBC Broadcasting, and later vice-chairman of General Electric, was a 30-year-old married law student when he was drafted. He had passed the bar in New York and was assigned to a Civil Affairs unit outside of Albany.

His team was preparing to “go in and manage a town or small city that had been deemed safe enough to rehabilitate.”

The problem? None ever was — so they never embarked on their mission.

Scull, upon receiving his law degree, served as an Army intelligence officer in Europe, but was assigned to Vietnam near the end of the war. He reported to the U.S. headquarters in Saigon. His first job was to write an intelligence history of the conflict.

He understood how powerful the Tet Offensive was in swaying public perceptions about the determination and resourcefulness of the enemy.

“I read about [the war intelligence efforts], thought about things and wrote up a history with some creative ideas, including this observation about Tet,” Scull said. “So it went up about four or five levels in a huge chain of command at headquarters. [But] Col. Somebody decided that it didn’t look enough like his press releases he had been approving for the past five years, so he threw it in the trash can and just stapled together his press releases. And that was the official history of the war.”

Zachary served as a commissioned officer in the Finance Corps at Fort Bliss, Texas. One of his duties was processing requests for conscientious objector status.

He said even before the Pentagon Papers, which revealed the extent to which the U.S. government had misled the public about the war’s progress, he could see the effort wasn’t enough.

“Just watching the practical application of our strategy, it was failing, and it was doomed to failure,” Zachary said.

He joined the Concerned Officers Movement, an antiwar organization of mostly junior officers who opposed the war.

Others witnessed the war playing out from Washington, D.C.

Levin sweated out an ultimately successful deferment while clerking for Chief U.S. District Court Judge Walter E. Hoffman in the Eastern District of Virginia. Afterward, he joined a Washington, D.C., law firm. He lived about 100 feet from DuPont Circle — where the music of bongo drums mingled in the air with bursts of tear gas and smoke from the occasional burning building.

“DuPont Circle was ground zero in the protest movement,” Levin said. “The Vietnam Embassy was just down the street.”

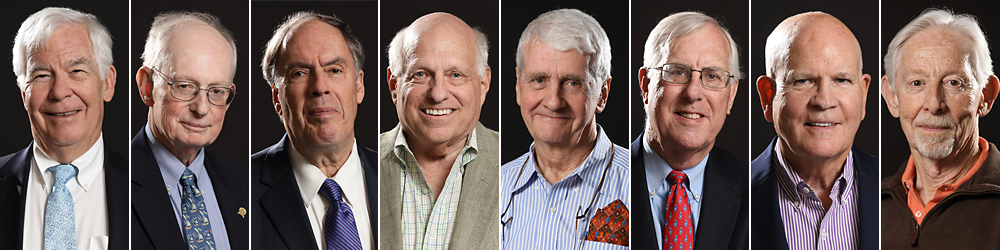

Class of 1968 members Weaver Gaines, Jack Hannon, Stuart Johnson, Ed Levin, Dave Scull, Pat Vaughan, Bob Wright and Don Zachary participated in the panel on Vietnam at Law Alumni Weekend.

Class of 1968 members Weaver Gaines, Jack Hannon, Stuart Johnson, Ed Levin, Dave Scull, Pat Vaughan, Bob Wright and Don Zachary participated in the panel on Vietnam at Law Alumni Weekend.

He represented some of the protestors who were swept up in mass arrests.

Johnson, who began a criminal defense practice in D.C. in 1971, also went to work amid the chaos in the streets.

He volunteered to represent soldiers who were convicted of fragging — an attempt to wound or kill a superior — in annual reviews before a parole board. He believed racial tensions and overzealous officers were often factors in the crimes. (Johnson noted he was much more “liberal” back then than he is now.)

All of the panelists used the opportunity not only to share memories, but to try to put them into perspective.

Gaines, who organized the panel, served in the Army as a rifle company commander in Berlin before being transferred to Long Binh, Vietnam, where he handled special courts martial as a non-JAG lawyer. He left for the Infantry Officers Basic Course at Fort Benning in August of 1968, right after taking the New York Bar Exam.

He said the disrespectful manner in which Americans debated the war back then, as well as the disgraceful treatment of returning soldiers, had a lasting impact that can be felt to this day.

“As far as our country is concerned, it commenced the process of poisoning our ability to have discussions with each other about things we disagree about,” Gaines said. “Where it used to be you could just say, ‘Hey, look, I think you are wrong,’ it became the case during the Vietnam War that you said, ‘You’re wrong, and also you’re evil.”

Panelists, as well as some of the attendees, questioned aloud whether they contributed enough, either during the war or after, and asked themselves how much pride they should take in their service. Emotions ran high.

“I’ve always had a sense of guilt that I didn’t do more,” said Johnson, who served in Civil Affairs in the Army Reserves.

Gaines said he carries with him the memory of a pal who didn’t make it back.

“My best friend in high school died with the 101st Airborne in 1968,” he said. “And from time to time ever since, I have wondered whether the fact that he died at the age of 22, and I’m now 74, [if I] have done enough with my life to sort of make it — not OK — but to live up to that loss that he had.”

He apologized for getting choked up.

“That’s OK,” a classmate assured.

Feeling the Draft at the Law School

<div>

“Moratorium to End the War” activities in Clark Hall on Oct. 15, 1969. The event was part of a coordinated effort nationwide. <em>Photo courtesy Virginia Law Weekly</em></div>

The Vietnam War and the draft hit home for students at the Law School in February 1968 with the end of graduate school deferments.

Selective Service Director Gen. Louis B. Hershey communicated the revised policy to draft boards that only medical and dental students, and those who were able to complete two years of study by that June, could receive a delay in draft consideration.

A Virginia Law Weekly editorial page piece on Feb. 22, 1968, described the mood at Clark Hall: “Shock, disbelief, anger, resignation — these were a few of the reactions displayed by law students and others over Friday’s announcement.”

For its April 25 issue, the newspaper polled students about their vulnerability to the draft and related topics. Of the 245 members of the first-year class, 164 responded to the newspaper’s poll, with 58 students stating they believed they could be drafted.

“Please help,” one student urged.

Law students weren’t the only ones concerned. Law school officials across the country, including at UVA Law, joined in rebuke of the sudden policy shift.

“The attitude of the Selective Service has caused increased uncertainty on the part of law school administrators and applicants,” Assistant Dean Albert S. Turnbull told the Law Weekly.

To offset losses to the second-year class, Turnbull selected a larger first-year class, by 50, for the fall.

In addition to more seats, prospective first-years also benefited from an early-offer trend nationally, with an increasing competitiveness among schools to lock down students able to commit.

For those who had been admitted and called up during or before their first year, however, readmission to the Law School was no guarantee.

“I hope we never have to turn one down,” Turnbull said of the veterans who would attempt to return.

Two years later, the Class of 1970 graduated 170 students out of the 244 with which it began.

In the fall of 1971, about 50 veterans returned to be members of that year’s second- and third-year classes.

Among them was David Kuney ’73, who served with the U.S. Marine Corps and is today senior counsel at Whiteford, Taylor & Preston in Washington, D.C.

“In a very real sense, the veterans are a measure of the changes which have evolved at the Law School over the last three years,” Kuney wrote for the Law Weekly. “When they entered Virginia, it was still a conservative, medium sized and predominantly segregated institution. There was very little student interest in ‘non-traditional employers’ such as environmental groups and legal aid societies. Poverty law was a fashionable topic which demonstrated that one’s heart was in the right place. The coat and the tie was uniformly followed and there wasn’t a sideburn in the class.”

The United States ended the draft in 1973.