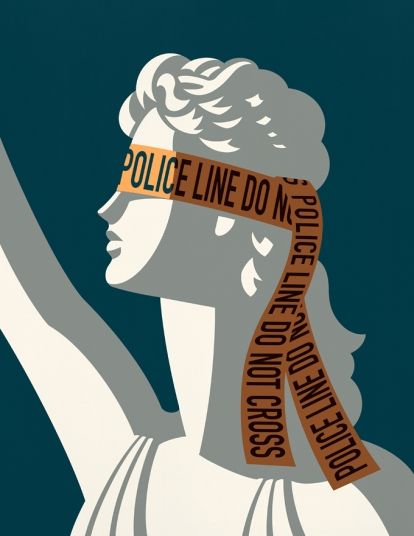

Federalism, separation of powers and the rule of law — the issues federal courts are grappling with in the United States — are both provocative and polarizing.

As the most consequential cases on immigration, the scope of executive power, abortion, election law, states’ rights and more work their way through the judicial system, any number of mechanisms and lower court judges can influence the ultimate disposition of the issue.

At times, the most significant judicial moves go unnoted by the media and the general public.

The University of Virginia’s federal courts scholars reflect on the trends they are seeing and how the outsized impact of process — from docket management to the issuance of stays — can shape society and the contours of democracy.

Avoiding Questions Over Separation of Powers

What happens when courts fail to expeditiously resolve cases involving executive privilege?

As a former Supreme Court clerk, Professor Payvand Ahdout has always kept tabs on the trends she sees in the federal judiciary. Over the past few years, she has forged her scholarly bona fides by backing these observations with data that reveal what’s going on behind the scenes. In 2022, the Yale Law Journal honored Ahdout as the journal’s inaugural Emerging Scholar of the Year.

In her latest paper, “Separation-of-Powers Avoidance,” forthcoming in the Yale Law Journal, she looks at how the federal appellate courts in recent years have gone to great lengths to avoid questions about separation of powers in cases in which Congress and the executive branch are in conflict. The result, she theorizes, is a distortion of legal meaning and the creation of vacuums that will ultimately be filled by someone other than a judge.

“Courts are trying to avoid compelling officers to do something — that’s the main thrust of this paper,” Ahdout said in an interview about the paper on UVA Law’s “Common Law” podcast. “But I think that has a whole host of implications for how it affects the merits and getting decisions on the merits.”

Ahdout’s research revealed how this pattern shapes the outcome of matters ranging from discovery, to standing, to mandamus to statutory construction. Applied to clashes between Congress and the president, it muddles the bounds of executive privilege and allows the executive branch to run out the clock on congressional subpoenas — via remands to lower courts to answer separation of powers questions — when an appellate court wouldn’t hesitate to address the merits of a congressional subpoena of a private party.

“There’s nothing barring a court of appeals or the Supreme Court from taking the standards that it articulates and applying them in the case at hand, instead of remanding,” Ahdout said. “So it’s the disparity between cases involving the executive and Congress as parties, and non-separation of powers cases that might involve similar doctrines, that is particularly striking for me.”

The federal courts are flush with congressional subpoenas and executive privilege claims right now, in part because of the “aberrational events” surrounding Donald Trump’s time in office, Ahdout said. But the doctrines being applied to these cases have a tendency to take on a life of their own, she cautioned.

The federal courts are flush with congressional subpoenas and executive privilege claims right now, in part because of the “aberrational events” surrounding Donald Trump’s time in office, Ahdout said. But the doctrines being applied to these cases have a tendency to take on a life of their own, she cautioned.

“When you look back and see where doctrines like executive privilege come from, most cases have at their inception something going on during the Nixon era, which people thought was aberrational,” Ahdout said. “And the executive privilege that Nixon was claiming is the same one that Barack Obama was claiming, and so once you create a tool or you develop a doctrine, I don’t think you can then take the worms and put them back in the can.”

Whether this type of avoidance is a good or bad thing is beside the point for Ahdout, who says she hasn’t decided that for herself yet.

“But if we’re relying on courts to tell us, ‘This is what the law is,’ what we’re getting is not an articulation of what the law is,” Ahdout said. “The court isn’t telling us exactly what the constitutional contours of executive privilege are.”

—Melissa Castro Wyatt

A Standard for Administrative Stays

Can consistency help temper the impact of cases that affect millions?

“Administrative.” It’s a word that calls to mind minor housekeeping matters — maybe boxing up dusty manila files — rather than the kinds of federal cases that affect millions of lives. However, according to a recent article by Professor Rachel Bayefsky published in the Notre Dame Law Review, federal judges’ administrative stays have had real-world consequences in recent high-profile cases involving abortion, homelessness and immigration.

An administrative stay allows federal courts to halt the effect of legal proceedings until a ruling is made on a party’s request for expedited relief — often a request for a more extended stay.

Despite the potential for such stays to affect lives and policies in these areas, Bayefsky says, federal courts have yet to introduce a uniform standard for determining whether an administrative stay should be issued in a given case.

Despite the potential for such stays to affect lives and policies in these areas, Bayefsky says, federal courts have yet to introduce a uniform standard for determining whether an administrative stay should be issued in a given case.

Administrative stays affected Texas women’s ability to have an abortion even before the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade. During the pandemic, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott issued an executive order postponing certain medical procedures, including abortions. When the federal district court blocked enforcement of Abbott’s order with regard to abortions, Texas officials appealed, seeking administrative stays to block the lower court’s ruling on an expedited basis.

The Fifth Circuit issued two administrative stays, portions of which lasted 19 days. Critics argued that the stays — which temporarily barred certain abortions — effectively denied some women’s constitutional rights and elevated their health risks.

Texas officials, on the other hand, argued in favor of the administrative stay because it preserved government power to protect public health during the pandemic.

“Administrative stays underscore the difficulty of devising value-neutral mechanisms for guiding the courts’ exercise of their discretion,” Bayefsky writes.

Her paper presents a series of recommended standards for determining whether a court should issue an administrative stay.

Among these recommendations is that stays should only be granted for a limited period of time, to promote legitimacy and consistency in the court system. Another is that for efficiency’s sake, some types of cases involving irreparable harm — such as those involving the death penalty or deportation from the United States — should automatically receive an administrative stay.

Bayefsky’s proposed standards “are meant to limit the influence of merits-based reasoning in the decision to grant an administrative stay,” she writes. “These steps would help to underscore that administrative stays are a docket-management device rather than an occasion for courts to opine on a controversial matter.”

—Fran Cannon Slayton ’94

Standing Too Tall

The Supreme Court is considering the boundaries of states’ standing to sue the federal government.

Fun fact: The state of California sued the Trump administration at least 122 times, averaging one new lawsuit every 12 days.

Since Donald Trump left office, the state of Texas has been in hot pursuit of the Biden administration, having filed at least 27 suits against the federal government since the White House changed hands. In one of those suits, United States v. Texas, the Supreme Court is considering the limits around states’ standing to sue the federal government.

In its Texas brief, the United States cites a recent article by Professors Ann Woolhandler and Michael Collins, “Reining-In State Standing,” which argues that current standing doctrine was designed for individual plaintiffs and there should be a presumption against state standing.

“If one believes that standing doctrine is an important structural limitation on the federal courts’ ability to make pronouncements of law restraining the political branches and other parties, then the upsurge of state-initiated suits is a matter of concern,” they write.

The impetus for U.S. v. Texas is the way the federal Immigration and Customs Enforcement Agency has prioritized the removal of different categories of immigrants under different administrations. In a country with 11 million undocumented immigrants, the priority has shifted from one administration to another, and Texas and Louisiana now allege they have standing to challenge these guidelines because they will increase the number of undocumented immigrants in their states, and so increase the incarceration, education and health care costs for the state. Under the theory of standing, these higher costs are the cognizable injury.

Woolhandler and Collins propose limiting state standing to cases in which states are the direct regulatory objects of federal statutes and regulations.

In a post on SCOTUSBlog, Professor Amanda Frost, who joined the faculty last fall, seconded her new colleagues’ position, writing that their approach would fit more comfortably with states’ traditionally limited role as litigants before federal courts.

“Under the tripartite requirements for standing, a plaintiff must show an ‘injury in fact’ that is traceable to the challenged action and redressable by a court,” Frost writes.

But that standard gives states “enormous leeway” to claim injury on behalf of themselves or their citizens “because almost any change to federal policy will have a fiscal impact on a state and its residents.”

Limiting states to standing as regulatory objects would help to restore some limits on state standing, Woolhandler and Collins write in their article. That would “reinforce the principle that Article III courts do not exist to resolve the policy disputes between governments,” they write in their conclusion.

Collins is the Joseph M. Hartfield Professor of Law, Frost is the John A. Ewald Jr. Research Professor of Law, and Woolhandler is the William Minor Lile Professor of Law and the Armistead M. Dobie Professor of Law.

—Melissa Castro Wyatt

A Matter of Personal Precedent

Is a justice’s personal consistency a building block of the rule of law or a political grenade?

Over the past year, Professor Richard M. Re’s analysis of justices’ use of “personal precedents” at the Supreme Court has attracted attention from many corners, including the Harvard Law Review, which published his article on the topic this past January, and The New York Times, which previewed it back in April 2022.

Re defines “personal precedent” as a judge’s propensity to adhere to her own previously expressed views of the law, including previous court opinions, law review articles, speeches and confirmation testimony.

The Times treatment preceded the abortion-opinion leak in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health by less than a month, by which point there was little question that, as former appeals Judge Richard A. Posner warned in 2008, “If changing judges changes the law, it is not even clear what law is.”

Re, however, argues that the apparent “choice between impersonal law and personal whimsy poses a false dichotomy.” He argues that adherence to one’s previously expressed legal views offers a path to decision-making that is “both personal and law-like.”

Personal precedents will always play a role when a justice is faced with open questions or with ancient precedent that they believe to have been based on prejudice, ignorance or methodological confusion, Re says. Moreover, justices are predisposed to hold fast to their previously expressed views to protect both their professional integrity and their “celebrity brand” and legacy. Majority opinions often incorporate — or even avoid upsetting — a particular justice’s personal precedent in order to win that justice’s vote, he writes.

As a practical matter, personal precedent adds an element of predictability that “facilitates settlements and streamlines litigation efforts.” A consistent dissenter, for example, may help point the way toward clearing up a doctrine’s muddied status quo, he writes.

Re also uses an ironic pre-Dobbs twist to illustrate the ways in which personal precedent can help reinforce a shaky institutional precedent: In Planned Parenthood of Southeast Pennsylvania v. Casey, the constitutional right to abortion was essentially preserved because of personal precedent. For example, the controlling opinion included a string citation of six of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s previous opinions, all lending support for a new “undue burden” test for abortion restrictions.

Re also uses an ironic pre-Dobbs twist to illustrate the ways in which personal precedent can help reinforce a shaky institutional precedent: In Planned Parenthood of Southeast Pennsylvania v. Casey, the constitutional right to abortion was essentially preserved because of personal precedent. For example, the controlling opinion included a string citation of six of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor’s previous opinions, all lending support for a new “undue burden” test for abortion restrictions.

Critics of personal precedent as guiding principle, such as William & Mary law professor Allison Orr Larsen ’04, warn that it turns every confirmation hearing into a zero-sum game that cannot end well.

“The endgame is an even more polarized Supreme Court with very little room for consensus and common ground,” Larsen said in The New York Times piece.

Re acknowledged that perspective but said, “My take is that personal precedent is already here, so we can’t ignore it. And it’s also virtually impossible to get rid of.”

Instead, we might look into our political toolkits to manage its impact.

“Perhaps seeing personal precedent for what it is strengthens the case for court reform — potentially including voluntary judicial term limits,” Re noted, gesturing toward another area of his scholarship.

Re is the Joel B. Piassick Research Professor of Law.

—Melissa Castro Wyatt

Seeking a Unified Theory of Constitutional Torts

A new American Law Institute restatement will clarify public officials’ liability for constitutional torts.

Since at least 1871, when the predecessor to 42 U.S.C. Section 1983 was enacted, money damages have been authorized for violations of constitutional rights. Written shortly after the Civil War, the law was originally aimed at the Ku Klux Klan but has been interpreted to apply to all constitutional violations by those acting under color of state law.

As cases were brought, a range of defenses for public officials evolved, from absolute immunity — for the president, legislators, judges and sometimes prosecutors — to qualified immunity for all others. Qualified immunity precludes liability unless the defendant’s conduct violated a “clearly established” constitutional right.

But what law is “clearly established”? By which court? With what degree of specificity? And under what facts?

John C. Jeffries Jr. ’73, a David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law and former UVA Law dean, has been tapped by the American Law Institute to answer those questions and many others, along with former UVA Law professor Pamela S. Karlan. Jeffries and Karlan, now the Kenneth and Harle Montgomery Professor of Public Interest Law at Stanford Law School, will serve as co-reporters for ALI’s first restatement of the law on constitutional torts.

Constitutional tort discussions turn almost immediately to excessive force in policing “because that’s what everybody talks about today,” Jeffries said. “But the law of Section 1983 provides a damages action against anyone acting under color of state law. That includes school board members, it includes people who give or deny welfare benefits, and it includes people who make zoning decisions.” (The U.S. Supreme Court recognized an analogous right to sue federal officers in Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.)

In most of these contexts, qualified immunity is the crucial issue. As applied to excessive force, “qualified immunity is almost a negligence standard,” Jeffries said. “If a police officer or any other government official violates constitutional rights but makes a reasonable mistake, they’re not liable for damages.”

Under the Fourth Amendment, force is unconstitutionally excessive only if it is “objectively unreasonable.” But, when the law has been in flux, some courts have held that an officer may make a reasonable mistake about whether force is objectively unreasonable.

In other words, it’s possible for an officer to be reasonably unreasonable. The whole thing can feel a bit like a trip through a hall of mirrors.

“There is a good deal of variation in those cases, and it would be good to have a more uniform understanding of exactly what qualified immunity means in that context,” Jeffries said.

“There is a good deal of variation in those cases, and it would be good to have a more uniform understanding of exactly what qualified immunity means in that context,” Jeffries said.

Jeffries, who first joined the UVA Law faculty in 1975, has spent most of the spring semester outlining the black letter law for the restatement project and assigning other scholars to work as the initial drafters of the comments that will elucidate the complexities of each rule. He’s also started drafting his own comments on excessive force and which decisions count as “clearly established law.”

Although Jeffries has authored numerous books and textbooks, he expects this to be his largest undertaking to date, with final ALI Council and membership approval several years in the future.

Jeffries expressed pride in being one of five UVA Law faculty members who are currently serving as reporters or co-reporters for ALI projects. Others include Douglas Laycock, who is a reporter for “Restatement of the Law Third, Torts: Remedies”; Paul B. Stephan ’77, a reporter for “Restatement of the Law (Fourth): The Foreign Relations Law of the United States”; Richard J. Bonnie ’69, an associate reporter for “Restatement of the Law: Children and the Law”; and Rachel Harmon, an associate reporter for “Principles of the Law, Policing.”

Restatements are addressed to courts, while principles projects are primarily addressed to legislatures, administrative agencies and private actors.

Jeffries has written — often pointedly — about the complexities of constitutional tort law and qualified immunity since 1989. Some considered his 2013 Virginia Law Review piece, “The Liability Rule for Constitutional Torts,” to be his final say on the issue.

In it, he noted the widening gulf between constitutional tort doctrine’s priorities and the importance of the underlying constitutional rights that may have been violated. In that self-described attempt at a “unified theory of constitutional torts,” Jeffries concluded that current doctrine considers only the identity of the defendant and the nature of the act she performs, thereby losing any “underlying stratum of good sense.”

The ALI project has pulled Jeffries back into the field and given him and Karlan a formidable platform for a comprehensive accounting of the field of constitutional torts.

—Melissa Castro Wyatt

The Problem With Universal Injunctions

Are lower courts misinterpreting the Administrative Procedure Act?

What do travel bans, mask mandates and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program have in common?

In each case, lower federal courts have used universal remedies — in the form of a universal injunction — to block government policies from being carried out.

Professor John Harrison argues that lower courts using universal injunctions in this manner are misinterpreting what the law says about available remedies. He makes his case in a Yale Journal on Regulation Bulletin article, “Vacatur of Rules Under the Administrative Procedure Act.”

Universal injunctions direct the government not to take some action, such as enforcing a regulation, with respect to anyone, whether they are a plaintiff in a lawsuit or not, Harrison explained. When the U.S. District Court for the Middle District of Florida struck down mask mandates on public transportation, saying the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had exceeded its authority, it delivered a universal injunction that vacated the rule for the entire country.

“By giving a remedy of that kind, a single district court can have the kind of effect that usually only the Supreme Court has,” Harrison said, “without the benefits of percolation.”

In the past several years, legal scholars have hotly debated whether lower federal courts have authority to issue universal remedies. Lower courts often rely on section 706(2) of the Administrative Procedure Act in support of their authority to provide universal relief. Harrison said that’s a mistake.

In the past several years, legal scholars have hotly debated whether lower federal courts have authority to issue universal remedies. Lower courts often rely on section 706(2) of the Administrative Procedure Act in support of their authority to provide universal relief. Harrison said that’s a mistake.

“Many lower courts take the position that section 706(2) of the Administrative Procedure Act directs them to give universal relief in many circumstances,” Harrison said. “In doing so, they rely on statutory language stating that courts are to ‘hold unlawful and set aside’ agency actions … that are contrary to statute or unconstitutional.”

Harrison argues the “set aside” language of section 706(2) should not be interpreted as providing a remedy, such as “vacating” a rule. Rather, Harrison says that to “set aside” a rule under 706(2) should be interpreted as meaning “to disregard” the rule and not treat it as binding.

Furthermore, the idea of vacating a rule because it was unlawful “was unknown” to the drafters of the APA in 1946, Harrison writes. In the paper, he details why vacatur of rules was not recognized as a remedy.

“Section 706(2) does not authorize universal remedies,” Harrison said. “Questions of remedy are addressed by bodies of law other than the APA, such as statutory provisions governing judicial review of specific agencies and general principles of federal equity.”

In fact, Section 703 of the APA points to those bodies of law when it identifies proper proceedings for judicial review.

For these reasons, Harrison said, “Courts that rely on the words ‘set aside’ in section 706(2) … are looking in the wrong place.”

Harrison is the James Madison Distinguished Professor of Law and the Thomas F. Bergin Teaching Professor of Law.

—Fran Cannon Slayton ’94

Making a Federal Case

When can the federal government sue for relief on behalf of citizens?

When the federal government appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court to stop a Texas abortion law in the fall of 2021, the case, United States v. Texas, harkened back to a 19th-century railway strike case that is relevant today, says Professor Aditya Bamzai.

Bamzai, a former Justice Department lawyer who teaches and writes about civil procedure, administrative law and conflict of laws, appeared on the UVA Law podcast “Common Law” to talk about why In re Debs is still relevant. He explores the topic in a paper with Samuel L. Bray of Notre Dame Law School, “Debs and the Federal Equity Jurisdiction,” published in the Notre Dame Law Review in December.

The Debs case concerned the 1894 Pullman strike led by Eugene V. Debs, president of the American Railway Union and later a leader of the Socialist Party. A federal injunction ordered the strikers to stop interfering with train service, but Debs refused to end the protest. After being held in contempt of court, Debs appealed to the Supreme Court. He lost unanimously, with justices ruling that the U.S. government had a sovereign interest in using its own courts’ equitable remedies to ensure the mail ran smoothly, preserving the most important way goods traveled state to state at the time.

Many reviled the decision as an affront to the democratic process, calling it “government by injunction.” After Debs, injunctions continued to be “a really important, effective tool that the government and industry had to stop workers from striking,” ultimately leading to statutory reforms that became incorporated into modern labor law, Bamzai says.

Many reviled the decision as an affront to the democratic process, calling it “government by injunction.” After Debs, injunctions continued to be “a really important, effective tool that the government and industry had to stop workers from striking,” ultimately leading to statutory reforms that became incorporated into modern labor law, Bamzai says.

Making the case for a sovereign interest to sue also came up in the Texas case, in which the justices considered whether the federal government could stop the implementation of state law S.B. 8, which makes abortions illegal as early as six weeks into pregnancy.

The Texas law is enforced through private civil lawsuits rather than by state or local officials, making it difficult for opponents to sue, which prompted the federal government to step in on behalf of the state’s residents. A federal injunction initially paused the Texas law. When the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals stayed that injunction, the Supreme Court weighed in.

As Bamzai explains on the show, a narrow reading of Debs might suggest that, in the absence of statutory authorization, the government can obtain an injunction only when the government has a proprietary interest to protect. But in the Texas case, the Biden administration focused on the part of the Debs decision that implied a more sweeping holding, Bamzai and his co-author write — “that the federal government could invoke the fallback equitable option of ‘a right to apply to its own courts for any proper assistance whenever there was ‘injury to the general welfare.’”

Although the Supreme Court initially agreed to hear the Texas appeal, in December 2021 it dismissed the writ of certiorari as improvidently granted, and returned the case to the Fifth Circuit, which soon ended the hopes of S.B. 8 opponents. Just two months later, the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization turned the abortion debate in a completely new direction.

But the dismissal in the Texas case “only highlights that the issue will not go away, and the courts will continue to struggle with precisely when, and how, and why” the federal government can bring a suit to enjoin state laws with which it disagrees, Bamzai writes.

Bamzai is the Martha Lubin Karsh and Bruce A. Karsh Bicentennial Professor of Law.

—Mary Wood