Most of 2020 is behind us now, but the protests set off by the deaths of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery and others won’t soon be forgotten.

A broad cross-section of America is saying, “Enough.” A recent poll from The Associated Press and its research partner at the University of Chicago found that nearly all Americans support some level of police reform, including clear standards for use of force and consequences for officers who err.

As events unfolded and protests cropped up across the nation, some asked what the Law School can do to respond — not just in policing, but with all manner of injustice.

Professor Rachel Harmon, who directs the new Center for Criminal Justice at UVA Law, said UVA Law professors are combating problems on multiple fronts.

“From making policing less harmful and pretrial detention less common to improving trials and releasing the innocent, our faculty are on the front lines of criminal justice reform,” Harmon said.

The UVA Law community, which includes alumni focusing on solutions from practice, is working to help correct discrepancies affecting people of color, the poor and others disproportionately impacted by a system that experts say is too often stacked against them.

“This issue is a status report on the work we’re already doing on criminal justice reform, and a reflection on reforms yet to be achieved,” Dean Risa Goluboff said. “One of the Law School’s missions is serving the public, both through enabling and teaching our students, who are positioned to make an impact when they become attorneys, and by supporting the service of our faculty. I am gratified by how many of our faculty are making important contributions at this critical moment.”

Policing / Juveniles / Juries / Informants / Reform in the Classroom / Bail Reform / Pretrial Detention / Hate Crimes / Officer Errors / Court Fees / Mental Health / Exoneration

Policing

Governments need to rethink almost every aspect of traditional policing.

Over the summer, Professor Rachel Harmon and other scholars released a list of reforms to address problems in American policing. The authors’ report, “Changing the Law to Change Policing: First Steps,” explains why the structure and governance of policing should be rethought, while looking at the appropriate role of police in achieving public safety.

“We have a long way to go in figuring out how to achieve public safety fairly and with less harm,” Harmon said. “But in the meantime, there are immediate legal changes that can make things better.”

“We have a long way to go in figuring out how to achieve public safety fairly and with less harm,” Harmon said. “But in the meantime, there are immediate legal changes that can make things better.”

The report’s recommendations include eliminating qualified immunity for police, establishing national legal standards for use of force, and the development of accountability systems, such as the use of inspectors general, on the local level.

Harmon is among the authors who are also reporters for the American Law Institute’s Principles of the Law: Policing, which works with advisers from across the ideological spectrum to draft proposals to govern policing.

Her article “Why Arrest?,” published in 2016 in the Michigan Law Review, argues that arrests are not essential to policing in most cases.

In another work, “Promoting Civil Rights Through Proactive Policing Reform,” published in 2009 in the Stanford Law Review, she advocates for a more aggressive federal enforcement of police departments for civil rights violations — which she says could be achieved through calculated lawsuits and offering “safe harbor” for departments actively pursuing compliance.

Harmon is a leader in the field of police regulation. She teaches in the areas of criminal law and procedure, policing and civil rights, and often advises nonprofits and police departments on legal issues involving the police. She also helped found The Fountain Fund, a nonprofit that provides low-interest loans and financial counseling to people who have been incarcerated. She served as a law enforcement expert for an independent review of the events of Aug. 11-12, 2017, in Charlottesville.

Harmon moved into academia in 2006 after spending eight years as a federal prosecutor in the Criminal Section of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Virginia. She is the Class of 1957 Research Professor of Law.

Juveniles

Most juveniles convicted of crimes do not need to be housed in the juvenile system.

The juvenile justice system has traditionally been an early stop in the school-to-prison pipeline. How a youth is handled may make the difference between a productive adult and an imprisoned one.

Professor Andrew Block recently rejoined the faculty after serving for five years as director of the Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice. There, he instituted major reforms while in his official role, including reducing the number of youth in state facilities by almost two-thirds, closing two state correctional facilities, and securing legislative support to reinvest savings from those closures into a network of services for children and their families.

Professor Andrew Block recently rejoined the faculty after serving for five years as director of the Virginia Department of Juvenile Justice. There, he instituted major reforms while in his official role, including reducing the number of youth in state facilities by almost two-thirds, closing two state correctional facilities, and securing legislative support to reinvest savings from those closures into a network of services for children and their families.

“We were able to really transform a lot of the work of the agency,” Block said. “We implemented evidence-based practices and treatment programs across Virginia, and hit all-time lows for numbers of new cases coming into the system, numbers of youth on probation and the numbers of youth in locked facilities.”

He teaches the class Children and the Law, and continues to speak and write about juvenile justice reform.

Block is also currently serving as vice chair of Gov. Ralph Northam’s Commission to Examine Racial Inequity in Virginia Law. In the spring, student research assistants working with him provided commission members with an extensive summary of their research about racial disparities in various aspects of life in Virginia, as well as a set of policy recommendations that will help inform future action to address the disparities. Already, historic racist language in state law has been removed because of the work of the commission.

More recently, Block and his students have been tackling police and criminal justice reform. Block launched the State and Local Government Policy Clinic at the Law School this fall, and students are participating in the next phase of the commission’s work.

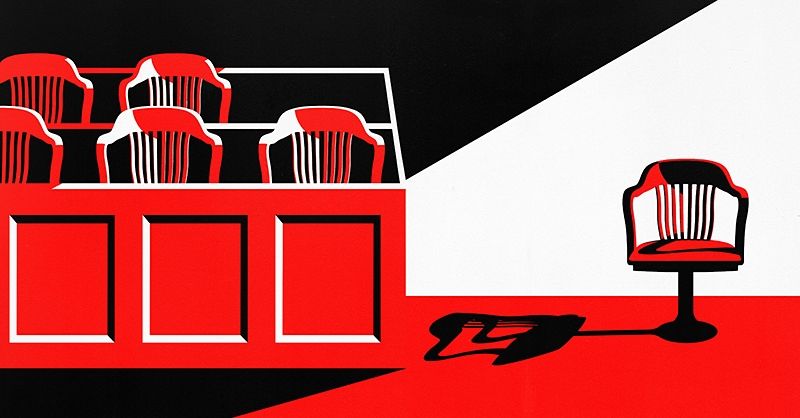

Juries

It’s not only possible, but it’s time, to end racial discrimination in jury selection.

Often when the public thinks of racial disparity in the criminal justice process, they think of the race of the accused. But the research of new faculty member Thomas Frampton also points to racial disparity among those who weigh in on guilt and innocence.

For his 2018 paper “The Jim Crow Jury,” published in the Vanderbilt Law Review, Frampton examined more than 13,000 peremptory strikes in recent criminal trials in Louisiana, which he says demonstrate that race continues to drive the selection of jurors. In addition, he studied the racial breakdown of 199 nonunanimous verdicts.

“The data I was working with offered an unprecedented measure of how race affects jury deliberations: viewing the same evidence in actual courtroom settings, black and white jurors regularly came to starkly different conclusions about guilt and innocence,” he said.

“The data I was working with offered an unprecedented measure of how race affects jury deliberations: viewing the same evidence in actual courtroom settings, black and white jurors regularly came to starkly different conclusions about guilt and innocence,” he said.

The paper called for aggressive measures to counter racial bias in the jury system” and declared that “relics of the original Jim Crow jury era — nonunanimous juries should be declared unconstitutional.

On the latter count, the U.S. Supreme Court agreed. In 2020, the court cited his paper twice in Ramos v. Louisiana, affirming that jury verdicts in criminal trials must be unanimous.

A more recent article, “For Cause: Re thinking Racial Exclusion and the American Jury,” which was published this year in the Michigan Law Review, looked at how juries are often crafted to have a certain racial com position by ruling out people for cause” — for example, they know the accused through a setting that may have created a favorable or unfavorable impression.

“Challenges for cause are racially skewed, in part, because the Supreme Court has insulated the challenge-for-cause process from meaningful review, he writes. “We need to rethink who is qualified to serve as a juror and how we select them.”

Frampton’s research draws on his background in American studies and his experiences as a public defender in Louisiana.

Informants

States should reduce or end the use of jailhouse informants.

The use of jailhouse informants, or “snitches,” is common nationwide in the most serious criminal cases, including death penalty cases. Of the 123 death row exonerations to date, 17% involved the use of jailhouse informants in the original trial, according to Professor Deirdre Enright ’92, who co-directs the Innocence Project at UVA Law.

“Prosecutors are allowed to dangle potential freedom to the most incentivized individuals in exchange for inculpatory testimony,” Enright said. “Were the defense to offer anything of value to a witness, they would surely face discipline or dismissal by the bar.”

Correcting the problem in Virginia is on the Innocence Project’s policy agenda for the year ahead. The group is working on a bill that would establish a statewide database to track the use of jailhouse informant testimony. Enright, co-director Jennifer Givens and staff attorney Juliet Hatchett ’15 will oversee student efforts in coordination with the New York Innocence Project.

Deirdre Enright ’92 and Juliet Hatchett ’15

“The U.S. Supreme Court has previously ruled that prosecutors must disclose to the defense discrediting information about state witnesses, including promised benefits and the witness’ criminal history,” said Brianna Miller ’22, student team leader on the project. “The database will provide greater transparency and allow for more prompt disclosure of the relevant information. This information is vital for the accused to be able to raise an adequate defense.”

Enright said an example of a state trying to correct the problem is Illinois, which has recently adopted stringent rules for prosecutors: They must give 30 days’ notice to the court, provide thorough discovery about the encounter that generated the account, be transparent about the inmate’s history of snitching and allow the defense pretrial hearings to test the reliability of the informant. In addition, cautionary jury instructions warn Illinois panels about the inherent unreliability of informants.

“Virginia has none of these measures in place, so our policy team’s efforts to draft curative legislation is both long overdue and essential,” Enright said.

Reform in the Classroom

<p>Professors Kim Forde Mazrui, left, and Anne Coughlin, right (with Lester Jackson), are focused on improving how they teach issues at the intersection of race and criminal justice.</p>

Teaching ‘Race and Criminal Justice’

When we caught up this summer with Professor Kim Forde-Mazrui, who runs the school’s Center for the Study of Race and Law, he was in the midst of planning a race and gender justice-themed symposium with the Virginia Law Review, scheduled for January, as well as preparing the fall course Race and Criminal Justice, which he first taught in the spring.

The new course prepares lawyers-in-training to understand the disproportionate influence that race has on the criminal justice system.

Forde-Mazrui is co-author of “Racial Justice and Law: Cases and Materials.” He will be teaching the course for the first time with Professor Josh Bowers, an expert in criminal law who served as a public defender early in his career.

Two takeaways (among many) Forde-Mazrui hopes students gain from the course: “Race remains a highly salient matter in the criminal justice system, and judicial doctrines that purport to protect racial equality are tragically inadequate because of flawed decisions by the Supreme Court.”

One thing he himself was surprised to learn in preparing the course is that relatively few conservative scholars have written in the area of criminal justice.

“I want to present a diversity of perspectives to my students, and it’s difficult to find conservative perspectives reflected in published legal scholarship, as opposed to blogs and other brief commentaries,” he said. “I welcome suggestions.”

Bowers, a criminal justice expert with a background in public defense, said he is excited to teach the course with Forde-Mazrui, whose materials he pulled from to teach a one-week version of the course at the University of Münster in Germany.

“Kim is an exceptionally generous and kind colleague, and he has developed a rich set of teaching materials,” Bowers said. They both said they look forward to the discussions they will lead and have with each other, drawing upon their backgrounds and individual perspectives.

“My primary expertise is race law; Josh’s is criminal justice. That makes us a perfect duo to teach Race and Criminal Justice,” Forde-Mazrui said.

Judging from spring feedback, the course has already had an impact on students.

“I am so grateful I took your class in my last semester of law school, because it has changed the way I am now engaging in this new period for our country,” wrote Sarah Houston ’20 in a thank-you email to Forde-Mazrui.

Forde-Mazrui is the Mortimer M. Caplin Professor of Law. Bowers is the F. D. G. Ribble Professor of Law.

Bringing Black Voices to the Table

Professor Anne Coughlin said she has learned much from her students over the years about why diversity in the profession, the bar and the bench “is essential if we are to have any hope of achieving racial justice.”

Coughlin said it’s also critical to bring in diverse voices to teach law students. Over the years in her classes Law and Public Service, and Criminal Investigation, she has hosted U.S. Judge Carlton Reeves ’89, retired Virginia Court of Appeals Judge James W. Benton Jr. ’70 and musician Lester Jackson to offer their perspectives.

“It hurts to put a burden on our Black neighbors to help educate us, and so I am very grateful to those who step up to help us, rather than just give up on us,” Coughlin said. Jackson is a resident of Charlottesville, who records music as the artist Nathaniel Star.

During a visit to Coughlin’s Criminal Investigations class, he had students close their eyes while he donned a black hoodie and sunglasses.

“I’m still the dude sitting here in these fantastic shoes — and a bowtie,” he said. “So why does this change? And I know you had to feel something when you opened your eyes. Those are the narratives that we need to try to change.”

Coughlin’s class that day focused on the U.S. Supreme Court cases Atwater v. City of Lago Vista, about police discretion in arrests for traffic crimes, and Terry v. Ohio, in which the majority said stop-and-frisk practices were legal.

“In both of these areas, there is substantial empirical evidence that race plays a really powerful role in the policing decisions,” Coughlin told the class.

At one point during the session, which is available at youtube.com/uvalaw, Jackson reflected on the pain he will feel when he teaches his young children how to safely encounter police.

“We shouldn’t have to have ‘the talk’ with our children,” he said, then paused for several seconds, holding back tears. At the time, he and his wife had a daughter and were expecting a second child. “At some point life will show her that she’s not viewed the same and I don’t want to not prepare her for that at the same time. … But how do I rob my daughter of her innocence?”

He added, “The world will do it if I don’t.”

Coughlin has also spent significant time working to persuade local law enforcers to bring felony charges against “the torch-burning mob” after the August 2017 white supremacist rally in Charlottesville. She said her efforts to hold individuals accountable for illegal acts, separate from their exercise of free speech, are ongoing. She is also currently involved in an effort with students and a team of lawyers from Covington & Burling to rewrite Virginia’s sexual assault laws, to ensure that prosecutors don’t have to prove “force, threat or intimidation” to meet the legal definition of rape.

Bail Reform

Progressive bail reform has little downside and could be instituted more widely.

A paper by Professor Megan Stevenson, “Bail, Jail and Pretrial Misconduct: The Influence of Prosecutors,” authored in 2019 and updated this year, examines bail reform measures under Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, who is a leader in the progressive prosecution movement.

“Dozens of jurisdictions across the country are engaging in bail reform, but there are concerns that reducing monetary incentives will increase pretrial misconduct,” Stevenson and co-author Aurélie Ouss of the University of Pennsylvania write about why they chose to study outcomes in Philadelphia.

Krasner’s office no longer requires bail to be set for misdemeanor offenses, for example, although a judge still has the final say. Stevenson found that such discretionary measures have had a positive impact, while not resulting in spikes in crime or significant increases in defendants failing to show up in court.

In fact, with a 22% increase in the likelihood that a defendant would be released with no monetary or supervisory conditions, there appeared to be no statistically significant downside.

In fact, with a 22% increase in the likelihood that a defendant would be released with no monetary or supervisory conditions, there appeared to be no statistically significant downside.

“This provides a unique opportunity to evaluate the primary justification for cash bail: that it provides incentive for released defendants to appear in court,” they state. “We find no evidence that cash bail or pretrial supervision has a deterrent effect on failure-to-appear or pretrial crime.”

Two of Stevenson’s other research papers were cited by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit as part of the 2018 decision in O’Donnell v. Harris County, Texas, et al. The court reaffirmed a district court ruling that the county’s bail system for misdemeanor offenses violated due process because it favored those most able to pay.

At UVA, Stevenson teaches Criminal Law as well as courses on evidence-based criminal justice reform and statistics for lawyers.

Pretrial Detention

Pretrial detention should be minimized and standardized across all 50 states.

Like his colleague Megan Stevenson, Professor Josh Bowers understands the many problems with fairness associated with pretrial detention. Bowers is the lead reporter for the Uniform Law Commission’s Pretrial Release and Detention Committee. He also served as a staff attorney for the Bronx Defenders early in his career.

In July, the commission released its model legislation for states under the title The Uniform Pretrial Release and Detention Act, which is meant to guide judicial decision-making. The overriding goal of the proposal is to eliminate wealth-based disparities in pretrial release and to ensure that the liberty of individuals is only restricted, after a rigorous process, to the extent required by a state’s legitimate pretrial interests.

In July, the commission released its model legislation for states under the title The Uniform Pretrial Release and Detention Act, which is meant to guide judicial decision-making. The overriding goal of the proposal is to eliminate wealth-based disparities in pretrial release and to ensure that the liberty of individuals is only restricted, after a rigorous process, to the extent required by a state’s legitimate pretrial interests.

The act also compels police, in some circumstances, to use citations instead of arrests.

“Our committee was a bipartisan group of academics, judges and lawyers, including prosecutors and defense attorneys,” Bowers said. “We represented a diverse set of viewpoints, but ultimately came together to produce an innovative template for state-level statutory reform, prioritizing pretrial release and minimizing the degree to which poverty leads to detention.”

Bowers is currently working on the article “

What If Nothing Works? On Crime Licenses, Recidivism, and Quality of Life,” which examines what it means to “defund” the police. In addition to his scholarly work, Bowers was a founding member of the city of Charlottesville’s recently formalized Civilian Review Board, which provides oversight of the Charlottesville Police Department. He is the F. D. G. Ribble Professor of Law.

Hate Crimes

Enforcement of damages against hate crimes should be more routine, and in proportion to the animus exhibited.

When thinking about criminal justice reform, one should consider the power of sanctions to influence behavior. Professor Andrew Hayashi asserts that preventing hate crimes will require doing more to address the animus behind the acts — and using economics in a way that currently isn’t being applied.

Hayashi wrote his 2019 paper “The Law and Economics of Animus” in part, he said, because prejudiced people continue to lash out, and the current methods of addressing the problem aren’t working. He is an expert in behavioral economics, which combines economics with psychology.

Hayashi wrote his 2019 paper “The Law and Economics of Animus” in part, he said, because prejudiced people continue to lash out, and the current methods of addressing the problem aren’t working. He is an expert in behavioral economics, which combines economics with psychology.

“The existence of animus is not an economics problem — it’s a spiritual or psychological problem,” Hayashi said. “But the fact that people act on their animus is an economics problem. Economics is about understanding how people respond to incentives, and so deterrence is a natural place for the use of economics.”

Forcing an offender to pay damages to his victim is the first prong of Hayashi’s plan because it goes toward meaningfully countering the intent.

“States should make it easier to allow for damage recoveries in the case of hate crimes,” he said. “Damages are better than fines or imprisonment in this way. They are especially unpleasant for people with animus for their victims because it means paying money to the person they hate.”

As the second prong of his plan, Hayashi recommends the development of community funds that could serve as a form of what he calls “solidarity deterrence.”

The money could be applied immediately after a crime to begin mitigating the impact of the harm.

As an example, he said, an anti-immigrant attack could be countered by the community channeling money to groups that help people immigrate legally.

Hayashi is the Class of 1948 Professor of Scholarly Research in Law and director of the Virginia Center for Tax Law.

Officer Errors

Officer-involved fatalities should be investigated the systemic way that medical mistakes and plane crashes are.

When someone dies from a medical mistake or an airplane crash, a team of professionals comes together and looks at all contributing factors, not just the actions of the doctor or the pilot. In these fields, such accidents are known as “sentinel events.

Professor Barbara Armacost ’89, a former nurse, says the investigation and prosecution of officer-involved shootings should be the same.

Currently, these inquiries focus almost exclusively on the actions of the officer who pulled the trigger with the public rightly seeking accountability for inappropriate use of force. But she sees a deeper problem with such a narrow focus, as indicated in the title of her paper on the subject: “Police Shootings: Is Accountability the Enemy of Prevention?,” published last year in the Ohio State Law Journal.

Currently, these inquiries focus almost exclusively on the actions of the officer who pulled the trigger with the public rightly seeking accountability for inappropriate use of force. But she sees a deeper problem with such a narrow focus, as indicated in the title of her paper on the subject: “Police Shootings: Is Accountability the Enemy of Prevention?,” published last year in the Ohio State Law Journal.

By only looking at the actions of the officer, or officers, in question, other fac tors or errors that contributed to the shooting may go unaddressed.

“We need to look beyond the limited time frame embraced by the current legal standard and view police-involved shootings as organizational accidents, writes Armacost, who is an expert in criminal justice, criminal procedure, torts, and race and law.

Armacost references the tragic death of Tamir Rice to demonstrate how systems-oriented, sentinel event review might be employed to investigate questionable police-involved shootings. In 2014, Officer Timothy Loehmann shot Rice, who was reported to be brandishing a weapon near a recreation center. It turned out that Rice was only 12 years old, and the weapon was a nonlethal air soft pistol.

Police experts and investigators universally condemned Loehmann’s partner, Officer Frank Garmback, for driving up so close to a reported active shooter” — rather than stopping, taking cover and waiting for backup, as police best practices would dictate. (Garmback was suspended for 10 days for violating multiple police department policies.)

By contrast, the investigations looking into the lawfulness of the shooting itself treated Loehmann’s position as a given. “That Garmback’s action may have increased the risk that deadly force would be necessary was deemed irrelevant to the question of whether the shooting was constitutionally allowable, Armacost says.

The shooting was deemed lawful under the circumstances, and both officers were cleared of constitutional error.

Additionally lost in the analysis, says Armacost, is consideration of other errors or systems weaknesses that might have contributed to the shooting, including inaccurate or incomplete information relayed to the officers by the dispatcher, breakdowns in communication, risks posed by realistic-looking but nonlethal guns, and weaknesses in police active shooter and de-escalation policies.

Court Fees

Optional court fees may be an unexpected solution to help defendants of lesser means.

Professor Darryl Brown ’90 argues that paying a fee for a trial could work to the advantage of poorer defendants in “The Case for a Trial Fee: What Money Can Buy in Criminal Process,” published in 2019 in the California Law Review.

Brown points out the many ways that relatively affluent defendants can “buy” advantages in the criminal process — through better legal representation, paying a fine in some cases instead of going to jail and being able to put up bail prior to trial, to name a few — whereas poorer defendants find themselves with fewer options.

Brown points out the many ways that relatively affluent defendants can “buy” advantages in the criminal process — through better legal representation, paying a fine in some cases instead of going to jail and being able to put up bail prior to trial, to name a few — whereas poorer defendants find themselves with fewer options.

He argues that adding another, optional court fee for defendants, ironically, may be the solution.

Through plea bargain agreements, defendants can reduce the costs of legal representation and the severity of a possible sentence by admitting guilt to fewer or lesser charges. Prosecutors often extend the agreements with the justification that it saves the state both the time and cost of a trial. But if that motivation is sincere, Brown says, then the state shouldn’t care if a trial does or does not happen, as long as another party foots the bill. That’s where his idea comes in. Brown says that a defendant should have the option, on

ce a plea bargain is offered, to pay a trial fee and go to court on the newly limited charges only — with the stipulation that the fee will be refunded if the defendant is acquitted. Such a change, he acknowledges, would raise a number of concerns and questions, some of which he attempts to address in his paper. He calls the piece a “thought experiment” that he hopes will be further examined for its possibilities. Brown is the O. M. Vicars Professor of Law and the Barron F. Black Research Professor of Law.

Mental Health

For many defendants with serious mental illness, providing court-ordered mental health treatment rather than sending them to jail or prison would better serve society.

An increasing number of people with serious mental illness are ending up in jail due to gaps in mental health services.

Professor Richard Bonnie ’69 and his co-author, Dr. Steven Kenny “Ken” Hoge, have proposed a new legal pathway to divert these people from the criminal process as soon as possible and commit them for mental health treatment.

“The tools now available to respond to these defendants are not serving their needs or the interests of society,” Bonnie said. “Their conditions get worse when they are in jail, and they are eventually released into the community without being connected to treatment.”

In many of the situations, Bonnie said, their arrests were for misdemeanors or nonviolent felonies related to the mental illness.

Bonnie and Hoge contend that the two traditional legal pathways to treatment in the criminal justice system are useless or counterproductive. One pathway is the insanity defense, but they point out the defense is rarely used except in very serious cases, because it typically leads to long-term commitment to a secure hospital. The second is being found incompetent to stand trial.

“A lot of mentally ill defendants are evaluated for competence, but a lot of time and money is spent moving them back and forth between the hospital and the jail, with little benefit to the administration of justice,” Bonnie said. The criminal charges are often resolved by a guilty plea and a short jail term, “but nothing is done to prevent another cycle of relapse and re-arrest.”

The goal, according to their draft proposal, tentatively named “Expedited Diversion to Court-Ordered Treatment,” would be to stabilize the patient enough while in the mental health setting so that he can be discharged into the community, where care would continue to be provided.

The goal, according to their draft proposal, tentatively named “Expedited Diversion to Court-Ordered Treatment,” would be to stabilize the patient enough while in the mental health setting so that he can be discharged into the community, where care would continue to be provided.

Bonnie has spent much of his career working for mental health law reform, including at the intersection of mental health services with the criminal justice system. Among other positions, he chaired a Commission on Mental Health Law Reform at the request of the chief justice of Virginia from 2006-2011 and an Expert Advisory Panel on Mental Health Reform for the Virginia General Assembly from 2016-19.

“We are planning on introducing a major overhaul of the statutes governing mandatory outpatient treatment in the upcoming session of the General Assembly,” Bonnie said of the latest reform efforts.

Bonnie has also advocated on such topics as risk warrants to remove guns from the hands of the mentally unstable, and the necessity of the insanity defense.

He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 1991 and has chaired more than a dozen studies for the National Academies on subjects ranging from elder mistreatment to underage drinking. In 2017, he chaired a study on policies needed to address the opioid epidemic in the U.S. More recently, he has been focusing on the implications of advances in knowledge about adolescent development for the justice system.

In addition to being the Harrison Foundation Professor of Medicine and Law at the Law School, he is a professor of both public policy, and psychiatry and neurobehavioral sciences. He also directs the Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy at UVA.

Hoge, a former director of the ILPPP, is a medical doctor on faculty at the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. He directs the Columbia-Cornell Forensic Psychiatry Fellowship Program. He was previously professor of psychiatry at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine and director of the Division of Forensic Psychiatry at Bellevue Hospital.

A Better Shot at Exoneration

<p>Professor Jennifer Givens, left, a director of the Innocence Project at UVA Law, prepares to give testimony at the Virginia General Assembly along with client Darnell Phillips, seated with his fiancee, Nichelle Ruffin. Phillips was paroled in 2018, but he has not been formally exonerated.</p>

Wrongly people in Virginia now have a much better shot at overturning their convictions because of the policy efforts of the Innocence Project at UVA Law.

As part of sweeping criminal justice reforms signed by Gov. Ralph Northam in April, the threshold for the Virginia Court of Appeals to grant a writ of actual innocence has been lowered in cases not involving biological evidence.

“It’s a new day in Virginia,” said Professor Jennifer Givens, who directs the Innocence Project along with Professor Deirdre Enright ’92. “The changes make the remedy available to more innocent people in Virginia and will lower the current burden of proof, which is incredibly high and nearly impossible to satisfy.”

The Innocence Project’s policy focus began at the beginning of the 2019-20 academic year. The primary team, then comprised of seven students and overseen by staff attorney Juliet Hatchett ’15, the inaugural Jason Flom Justice Fellow, advocated for amendments to the writ of actual innocence law that have now been incorporated.

“This type of work is something we’ve wanted to do for a long time,” Givens said. “Our team brainstormed the types of reforms we should be focusing on for this legislative session. We then worked with the New York Innocence Project and the Mid-Atlantic Innocence Project to establish a legislative agenda and plan, and Juliet and the policy team worked hard to implement that plan.”

The change in the law effectively puts the remedy within reach. As an appeals court considers how a reasonable set of jurors might determine guilt based on the new evidence, the standard now requires relief based on a “preponderance of the evidence,” versus the previous, higher bar of “clear and convincing evidence.”

The law also changed to allow a convicted person who previously pled guilty to petition for a writ.

“More than 95% of people plead guilty to a crime, but pleading guilty doesn’t necessarily mean a person isn’t innocent,” Hatchett said.

And the new law allows for more than one writ petition if the first isn’t successful, although significant new evidence must still be introduced each time.

As of the spring, only four people in Virginia had been granted a writ of actual innocence based on nonbiological evidence, Hatchett said. The new law went into effect July 1.

Virginia has a separate statute that pertains to the filing of a writ of actual innocence in cases that hinge on biological evidence. For that law, the policy team proposed allowing DNA testing to be performed at private labs. (“This will be particularly useful in cases where the Virginia Department of Forensic Science does not possess the necessary equipment or expertise,” Hatchett said.) The bill passed both the House of Delegates and state Senate unanimously, and the governor signed it into law after suggesting an edit to its language.

Jessica Joyce ’20, team leader for the students working on the project, researched the law in other states and investigated which Virginia legislators might be interested in sponsoring. Sen. John Edwards ’70 sponsored the writ of actual innocence legislation in the Senate, while Del. Charniele Herring sponsored identical language in the House of Delegates.

“The new writ of actual innocence law demonstrates that Virginia’s legislature is serious about trying to get things right in our state’s criminal justice system,” Joyce said. “The post-conviction DNA testing bill will allow courts to consider more DNA evidence when reviewing the convictions of those who claim innocence. As a bill that was passed unanimously by both the Senate and the House, it is also a wonderful example of how criminal justice reform is a bipartisan issue and how all policymakers can strive toward a more just Virginia, regardless of political affiliation.”

Joyce also deserves credit for pushing to start a policy team, which she first advocated for as a student in the for-credit Innocence Project Clinic, Hatchett said. Students in the yearlong clinic investigate and litigate claims of false conviction in Virginia.

Northam had signaled in advance that he wanted to make major changes to criminal justice in Virginia, including to the writ of actual innocence process.