Ruth Smith’s divorce was acrimonious. She and her husband, a physicist who once studied under Albert Einstein, had three children together. But that didn’t stop her from completing her bachelor’s in business education at Mississippi State College for Women, where her husband taught, before the couple split.

In 1945, with her children in tow, Ruth relocated to Virginia to serve as the registrar at Madison College in Harrisonburg, a school that trained young women to become teachers. (Today it’s James Madison University.)

She remarried, too — to a hotelier — and took his name, becoming Ruth S. Taliaferro.

She began her studies at the Law School in the fall of 1947, at age 39. It was the beginning of a mother-daughter alumnae story unlike any in the Law School’s history — one that spans from the formative years of the women’s rights struggle into the 1970s.

RUTH’S PERSPECTIVE WAS no doubt radically different than those of the young men, mostly in their 20s, whom she attended classes alongside.

“Mrs. Taliaferro’s education was interrupted by several considerable delays named Elizabeth, James and Verell,” the Virginia Law Weekly quipped in its Nov. 4, 1948, edition — then her second year.

The reason for the Law Weekly article was something more unusual than a woman studying at the Law School, which had happened on occasion since Elizabeth N. Tompkins ’23 broke the gender barrier in 1920.

Ruth Taliaferro’s daughter — Elizabeth “Betty” Taliaferro, 18 — had just entered the Law School, becoming the youngest graduate student at UVA.

“At present the Taliaferros plan to form a partnership upon graduation, and to practice law in Harrisonburg,” the Law Weekly piece continued, speculating that Betty’s brothers might one day join the mother-daughter practice.

The article ended with, “Mr. John Taliaferro of Harrisonburg, no lawyer, was not available for comment.”

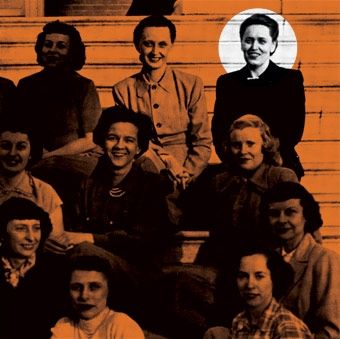

Ruth Taliaferro is pictured with her Kappa Delta sisters at the University of Virginia. She was also a member of the international legal sorority Kappa Beta Pi. The Barrister

ELIZABETH WAS ADVANCED. She graduated high school at age 14. She entered Madison College at 15, and obtained a degree in education, with minors in English and French, at 17.

She looked to take on law school next — but it was unclear if that would be allowed. “At the time, there was a Virginia statute that prohibited women under 21 years of age from attending ‘professional school,’” her obituary states. “There was a question as to whether this statute, which was intended to apply to nursing schools, applied to the UVA Law School. The University ultimately agreed to accept her if she made a reasonable score on the LSAT.”

That year, 1948, was the first year the test was offered, and she performed well.

With Ruth interested in staying to obtain her master’s in law, mother and daughter were on track to spend a lot of time together.

THOUGH THEIR CLASSES would have been different, mother and daughter were indeed “sisters in law.”

They were both charter officers in Kappa Beta Pi, the international legal sorority, which was installed at the Law School in January 1950. Ruth served as dean, the highestranking officer, and Elizabeth as corresponding registrar and historian.

Several other female law students completed the group.

At the first meeting, with the knowledge that major law firms in the South weren’t looking to hire women, the sorority’s faculty adviser, Professor Neill H. Alford, “suggested that a widening field existed in international affairs for women now being trained in the law,” the Law Weekly reported.

The Taliaferros’ time together as students was shorter than expected, however. Elizabeth left in the 1949-50 school year “for personal reasons,” according to her obituary.

Two of Elizabeth’s sons, Sam and Ted Allen, said the reason wasn’t anything controversial, but rather a story as old as parents and children.

“My grandmother drove my mother crazy,” Sam Allen said. “So she dropped out.”

Elizabeth taught sixth grade in Gordonsville, Virginia, then moved to New York City.

During her time in the Big Apple, she became a corresponding secretary for the American Red Cross and attended night classes at New York University Law School, where she reportedly had the highest grades in her class.

“BETTY’S MOTHER WAS a feminist before it was fashionable,” according to Elizabeth’s obituary. But Ruth wasn’t just interested in women’s rights. She supported equality for all.

After Ruth graduated in 1950 and before she was set to begin her LL.M. studies that fall, she and other grad students were surveyed regarding their opinions about the inclusion of black students at the graduate level, along with other race-related questions. Respondents were told they did not have to identify themselves.

Ruth wrote at the bottom of her survey, “[I] can sum up my whole philosophy on this subject in one sentence. ‘There, but for the Grace of God, go I.’ Why should the state of Virginia give me any better opportunity than it does any other citizen, black or white?”

She signed it, “Ruth S. Taliaferro.”

She and the three other students seeking advanced law degrees were joined for the academic year by Gregory Hayes Swanson, who won his lawsuit on Sept. 5, 1950, to become the first black student admitted to UVA.

Ruth vowed on her survey to be among those who created a welcoming environment.

This undated photo of the Law Library in Clark Hall demonstrates what the male-dominated law school environment was like circa 1950. UVA Law Special Collections

AFTER RUTH FINISHED her time at the Law School, stopping short of obtaining her LL.M., Elizabeth returned to UVA in the fall of 1952.

She landed a spot on the Virginia Law Review, becoming among the handful of women who had joined its ranks since the journal was first published, almost 40 years earlier.

“Miss Taliaferro is now the only girl on the Review and steps into the vacancy left by Miss. Margaret E. [Seiler] Gordon,” the Law Weekly reported that November.

But Elizabeth wasn’t filling a token spot. She earned the position, and against some pushback, according to her son Ted.

By writing onto the journal, she also got to know her future husband, Samuel N. Allen Jr. ‘53, the Law Review’s Virginia editor.

“During her public defense of her paper, my father needled her pretty good — to the point where my mother interrupted and said, ‘Who the hell do you think you are? Do you think you’re a little tin god?’ And my father said, ‘Actually, I do. [But] I think we [the Law Review board] should put it to a vote.’ So they put it to a vote, and they all agreed they were little tin gods.

“But what my mother didn’t know for many years was there was another member of the Law Review who was going to blackball my mom simply because she was a woman. And my dad, in the background, said, ‘Here’s the deal: You’re going to let that woman on, or I’m going to blackball every single other candidate, because she’s clearly written the best paper. And either we’re going to be intellectually honest, or we’re not.’ And she didn’t know for years that my dad had actually been the one to defend her.”

Elizabeth thrived on the review and graduated fourth in her class in 1953.

The next year, she married Sam, her champion. The ceremony was held in Richmond at the Thomas Jefferson Hotel (famous then for its marble pools containing live alligators).

“That day, she told Sam she wanted to have four boys, all exactly like Sam,” her obituary reads.

Her prediction of four sons would indeed come true.

ELIZABETH — NOW ELIZABETH ALLEN — worked in the latter half of the 1950s for the blue-chip Wall Street firm Lord, Day & Lord. She represented such clients as the Cunard Steamboat Line (which operated the famous Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth), The New York Times and the Pennsylvania Railroad.

Herbert Brownell Jr., who had been attorney general under President Dwight D. Eisenhower, served as her mentor at the firm.

But the couple found the pace of life in New York incompatible with how they wished to raise their children. The growing family relocated to Haddam, Connecticut, in the early 1960s.

By 1980, all of Elizabeth’s children were grown, so she decided to open her own general practice and become more involved in her community. She served as head of the Haddam Republican Party for several terms.

But her more lasting impact came in the form of an organization called Checkerboard Homes, which helped minority families obtain home loans from local banks.

Sam was a prominent attorney who worked with most of the banks in the central part of the state. That connection provided Elizabeth a unique opportunity to bend their ears.

“There was real segregation and red-lining going on in lending. So my mom kind of forced the presidents of all these banks into a meeting and just shamed them,” Ted Allen said. “She got all of the banks to agree to contribute to a fund called the Checkerboard Foundation that would make mortgages, but agreed not to ask any of the traditional census questions.”

Many area residents of Italian, Irish, African American and Slavic descent were newly empowered to become homeowners through Checkerboard.

“It was interesting to see how it affected the views of those bank presidents, who were kind of surprised, because the best-performing loans were the ones from the Checkerboard fund,” Ted said.

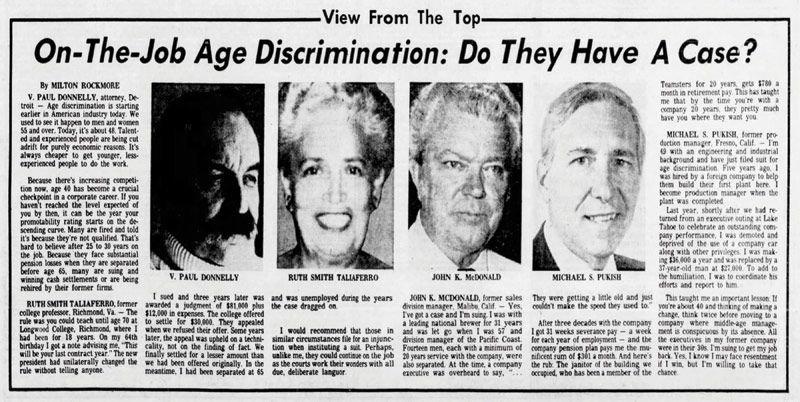

Ruth Taliaferro is seated (center) next to Willard Leeper, second from left. Leeper surpassed her to head the department, despite her complaints that she was more qualified. Longwood University, Greenwood Library Special Collections and Archives

RUTH’S LIFE TOOK a different path. She was named regional director of the National Association of Women Lawyers in February 1951. She was in charge of five states, including Virginia, and the District of Columbia.

During that time, as an ex-officio member of the governing body, she likely would have been party to the association’s efforts to draft a “Uniform Divorce Bill,” which was model no-fault divorce legislation proposed in 1952 that could be adopted by states across the country. The effort aimed to protect women at a disadvantage against husbands who shopped for the state with the most favorable divorce laws.

Mississippi, where Ruth had first married, did not have no-fault divorce law in place until 1976.

She practiced law for several years. Then the former registrar returned to academia. She joined the faculty of Longwood College in Farmville, Virginia, in 1955.

THE WOMEN’S SCHOOL, previously known as State Teachers College, was renamed in 1949 to reflect its growing number of degree offerings. (Today it’s Longwood University.) Ruth taught a wide variety of business courses — and even some involving law.

“It is not uncommon to find Mrs. Taliaferro in conference with several students of her law and society class, discussing a major issue in current ethics,” the school’s 1969 summer alumni publication reads.

An involved academic, she served on committees, including the presidential search committee and, later, the President’s Advisory Council. She also served as vice president of Longwood’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors. She served as a faculty adviser to several student groups.

On the legal side, Ruth had gained admission to practice before five federal courts, including the U.S. Supreme Court, a credential she earned in 1973.

“I think my greatest feeling about being admitted to practice before the Supreme Court is that it means I am a part of that long line of what I hope may be termed ‘valiant’ women who have fought for better opportunities for females,” she told the Longwood newspaper, The Rotunda, in April of that year. “This is my legacy to my grandchildren and other young women who come after me.”

Although she never completed the final requirements to receive an LL.M., her LL.B. and graduate coursework were of particular pride to Longwood. The school at times claimed her legal education as another doctoral-level checkmark for its faculty.

Ruth was a qualified and valuable professor by almost any measure.

THE EQUAL RIGHTS AMENDMENT was first introduced to Congress in 1923 by Alice Paul of the National Women’s Party. The effort sought equal status for men and women in such matters as employment, divorce and property rights.

Almost 50 years later, after achieving Senate approval on March 22, 1972, the proposed amendment finally cleared both houses of Congress and was on to the states. The amendment required ratification by three-fourths — or 38 — of the 50 states in order to take effect.

There were numerous players in the struggle to pass the amendment, and Ruth was one. She represented the Virginia Federation of Business and Professional Women before the General Assembly at the hearing to consider ratification.

She was the final speaker, and her rousing comments reportedly earned her a standing ovation.

The amendment did not pass in Virginia, however.

“I love Virginia as much as anyone does,” Ruth said in a 1974 debate on the ERA held at Longwood, “but that doesn’t mean we’re not in the Dark Ages about some things.”

Her male debate opponent argued “you have been emotionalized” and that “emotionalism makes bad laws.”

<p>Ruth Taliaferro teaches a class at Longwood. <em>Longwood University, Greenwood Library Special Collections and Archives</em></p>

IF SHE WAS EMOTlONAL, she had good reason. Ruth was hired at lesser pay than her male counterparts. She wasn’t promoted to associate professor until 1968 — 13 years after she had started. She was passed over for department head in favor of, to her mind, a lesser-qualified male candidate. She was never promoted to full professor, despite holding advanced degrees. (The interim between promotions would have been too short given her pending retirement, the administration argued.) And she was being forced to retire, despite having tenure under her original hiring agreement that said she could teach until age 70.

Longwood apparently wasn’t the only school in Virginia’s higher-education system that treated women differently; additional teachers joined the complaint. They sought “monetary and injunctive relief on behalf of themselves and others similarly situated.”

The women were represented by Philip J. Hirschkop, of Loving v. Virginia fame, as well as other attorneys, in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia.

Hirschkop, during the time period, was taking on important cases related to women and educational settings. In fact, he had joined John Lowe ‘67 in representing Virginia Scott and three other young women in their lawsuit against the University of Virginia to force undergraduate coeducation — a case they won in 1969.

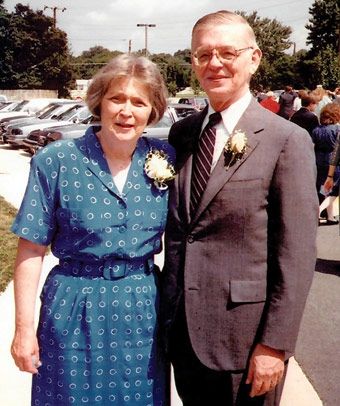

Elizabeth and Sam Allen ’53 attend their son Ted’s wedding in 1986. Courtesy Ted Allen

“THE EVIDENCE REFLECTS that the plaintiff was hired at a lower rate of pay than her male counterparts,” Judge Robert Reynold Merhige Jr. wrote in his opinion about Ruth’s case. “It was uncontroverted that Dr. [Francis G.] Lankford offered Mrs. Taliaferro the lower paying position because the men in the department would not like it if she was given a higher position. Dr. Lankford further explained that Mrs. Taliaferro was old enough to understand how these things were.”

Despite such findings, the charges of sex discrimination did not stick.

The court maintained that a current Longwood president could not be held accountable for a past president’s actions. Henry Irving Willett Jr. was the president in Ruth’s final years before retirement, and the court did not find examples where he treated her, or women in general, differently than their male counterparts.

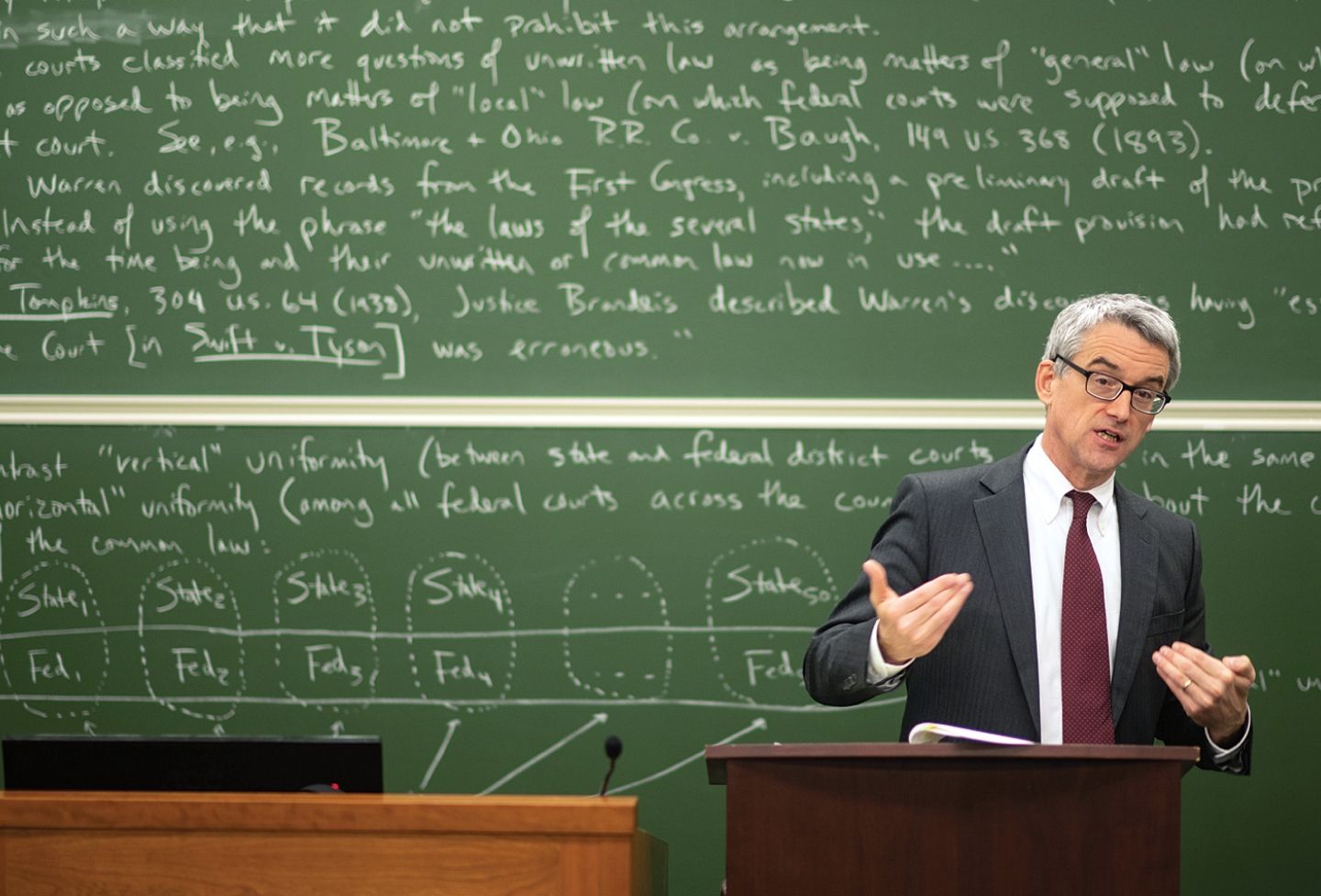

“In her case, all of these problems were complicated by the fact that she had to sue individual officers of Longwood University rather than the university itself,” said Professor George Rutherglen, an expert in employment discrimination who has been teaching at UVA Law since 1976.

“That meant that many of the instances of sex discrimination that she alleged were attributable to individuals who had long since left the university, well before the actual defendants whom she could sue. Her case was therefore an awkward one to bring up the constitutional claims she alleged.”

BUT RUTH HAD a separate complaint within the same case, one of early termination — essentially age discrimination.

The court ruled she should have been allowed to remain in her position until age 70. Although the academic policy changed during her tenure, there was no previous understanding that the policy might be changed, which helped her case.

Ruth won five years’ back pay. The judgment provided a measure of validation for her cause.

However, her fortunes were reversed in 1978.

The defendants, now represented by the Virginia Attorney General’s Office, challenged the decision. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit cited Carey v. Piphus, which was decided after the District Court decision, in overturning. Carey held that “absent proof of other compensable tort injury, a plaintiff deprived of procedural due process can recover only nominal damages.”

The case was remanded with directions to dismiss. In retrospect, there was probably not much else she could have done, Rutherglen said. She was ahead of her time.

“Ruth Taliaferro did not pursue her claims under Title VII [of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, prohibiting employment discrimination based on sex and other protected attributes], which came into effect for public universities on March 24, 1972,” Rutherglen said. “She dropped this claim from her complaint, probably because many of the acts of sex discrimination that she alleged occurred before the effective date.

“Her claim today would be brought directly against the university under Title VII. She could also bring her claims of age discrimination under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act. At the time, however, it had a ceiling on coverage of age 65. She was over 65 at the time of alleged discrimination against her on the basis of age.

“In short, she would have had much better claims, in fact a clear winner under the ADEA, after the amendment of these statutes.” (Relevant amendments to the ADEA passed in 1974, to include government employees, and in 1986, to remove age caps.)

EIGHT YEARS AFTER her loss in court, on Oct. 12, 1986, Ruth died and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery next to her husband, a World War I veteran.

But before then, she was able to witness Sandra Day O’Connor become the first woman on the U.S. Supreme Court, Geraldine Ferraro become the first woman to be a vice presidential nominee, and Sally Ride become the first American woman in space.

What she didn’t get to see was the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. Neither did Elizabeth, a less-active supporter of women’s rights, who died on Oct. 18, 2017.

Their differences were so profound that the women were estranged until Ruth’s passing.

“My grandmother kind of got to the point where she presumed people would behave poorly, unless told not to,” Ted Allen said. “My mother was exactly the opposite. She just had an unwavering faith in human nature. Given the opportunity to do the right thing, she thought, they would.”

Although Congress extended the deadline for ERA ratification to 1982, only 35 states had approved the amendment by then.

State ratification efforts continue to this day, but scholars dispute whether ratification past the deadline is possible.