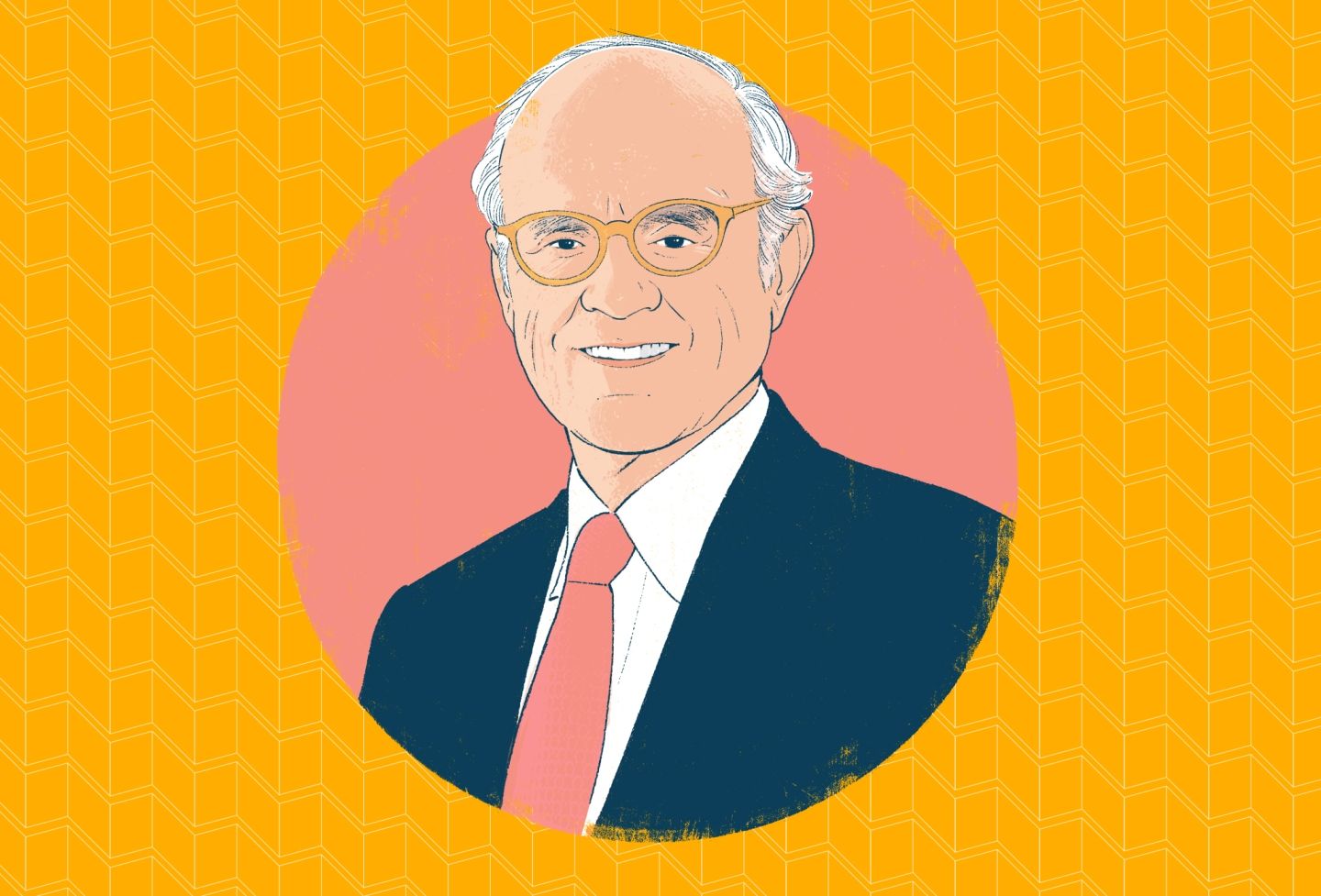

UVA basketball fans might owe Law School graduate Don Jackson ’90 a special debt of gratitude. Without Jackson, there would have been no buzzer-beating shot by forward Mamadi Diakite to send the Hoos to the Final Four and eventually win an NCAA championship in 2019. When Diakite, who hails from Guinea, struggled to gain NCAA eligibility, he hired Jackson.

Over the past four decades, hundreds of professional, collegiate and amateur athletes, both in the U.S. and around the world, have hired Jackson to represent them in whatever sort of dispute they happened to be having, from NCAA compliance issues to contracts, family law matters and beyond. When University of Memphis basketball coach Penny Hardaway was accused of recruiting violations, he hired Jackson. When Howard University lacrosse player Taylor Matthews was kicked off the team in the spring after accusing her coach of not supporting her mental health, she hired Jackson.

“My practice is sports-based,” Jackson said, “but it’s not entirely sports.”

JACKSON’S FIRM, based in Montgomery, Alabama, is called The Sports Group, but to call it a firm is something of a misnomer. Right now, it’s just him. One advantage, though, to being as prominent and successful as Jackson has been is that it’s less important to advertise. Many of his clients now come by word of mouth. In fact, Jackson’s office has no name on the door or in the building’s directory.

Jackson’s hours are also unconventional. His day usually begins at 1 a.m.; he takes a workout break at 4 a.m. and closes shop by mid-afternoon. That comes with the job when your clients are in places like South America, Africa and Asia.

“Quite often, I’ll have to get local counsel in these places, because I need someone on the ground who I’ve worked with,” he explained. “You’re going to have to collect a lot of information that will require a lot of legwork.”

In the early days, that meant Jackson spent a lot of time on the road too, but much less so in recent years.

“I’ve got an aversion to travel,” he admitted. “It was enjoyable early on and not so enjoyable now.”

He makes an exception for trips to England to visit his son Theo, who earned his undergraduate and master’s degrees there and is now an intern with the English Premier League’s Burnley Football Club.

HE HAS A REPUTATION for tenacity and bluntness in representing players—including one he legally adopted. Ousmane Cisse, born in Mali, moved to Alabama under Jackson’s guardianship and was drafted out of high school by the NBA’s Denver Nuggets in 2001. (Cisse played for several years in Israel, Cyprus and France, and even had a stint with the Harlem Globetrotters.)

UVA men’s basketball coach Tony Bennett—who can thank Jackson for getting Diakite on the court—said of Jackson, “I think everyone in college sports has used his expertise. He’s excellent at what he does and has helped so many people.”

Sonny Vacarro, former head of Nike, calls him “a defender of the downtrodden”—despite Jackson’s clients being on the opposite side of many an endorsement deal with Vaccaro.

Jackson enjoys the accolades but does not let them go to his head. As he told a reporter for the Montgomery Advertiser in 2020, “My family loves me, my clients respect me, and my dog won’t bite me as long as I buy him the right dog food. Everything else is secondary.”

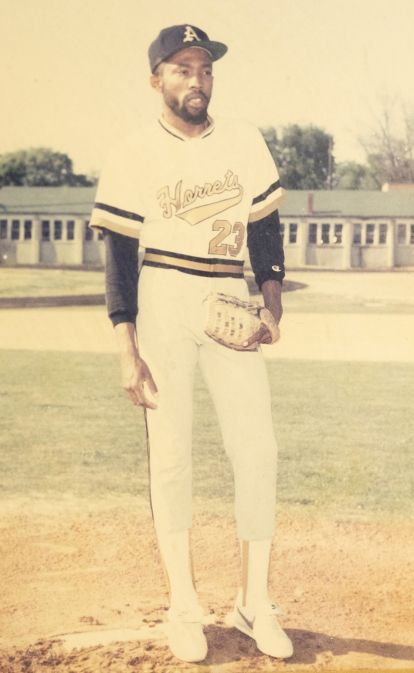

JACKSON’S EXPERIENCES with collegiate sports began as a player. After being recruited by multiple colleges as a basketball player, he ended up playing baseball at Alabama State University and was a Rhodes Scholarship candidate. Still, he insists that he never considered a career in sports—as an athlete or an attorney—when he entered law school at UVA. He lived on the Range his third year and cites his Torts professor, Saul Levmore, and former UVA President Robert O’Neil as favorites.

Jackson still brushes up on tort law by listening to Levmore’s current University of Chicago lectures online. And as much as he enjoyed O’Neil’s commercial law classes, Jackson said the professor’s influence was greater outside the classroom.

“He knew I was from Alabama and that my intention was to return there,” Jackson said, “but he challenged me in a strictly intellectual way to not limit myself to a particular type of practice area.”

After graduation, Jackson did indeed return to Montgomery, where he worked in corporate tax and municipal finance work for a small firm. Try as he might to put sports in his rearview mirror, his connections kept creeping back up on him. Two years out of law school, he represented players in the 1992 MLB and NFL drafts. Shortly afterwards, Jackson went into practice for himself, mixing sports work with other types of commercial law. By the end of that decade, his practice became entirely sports-based.

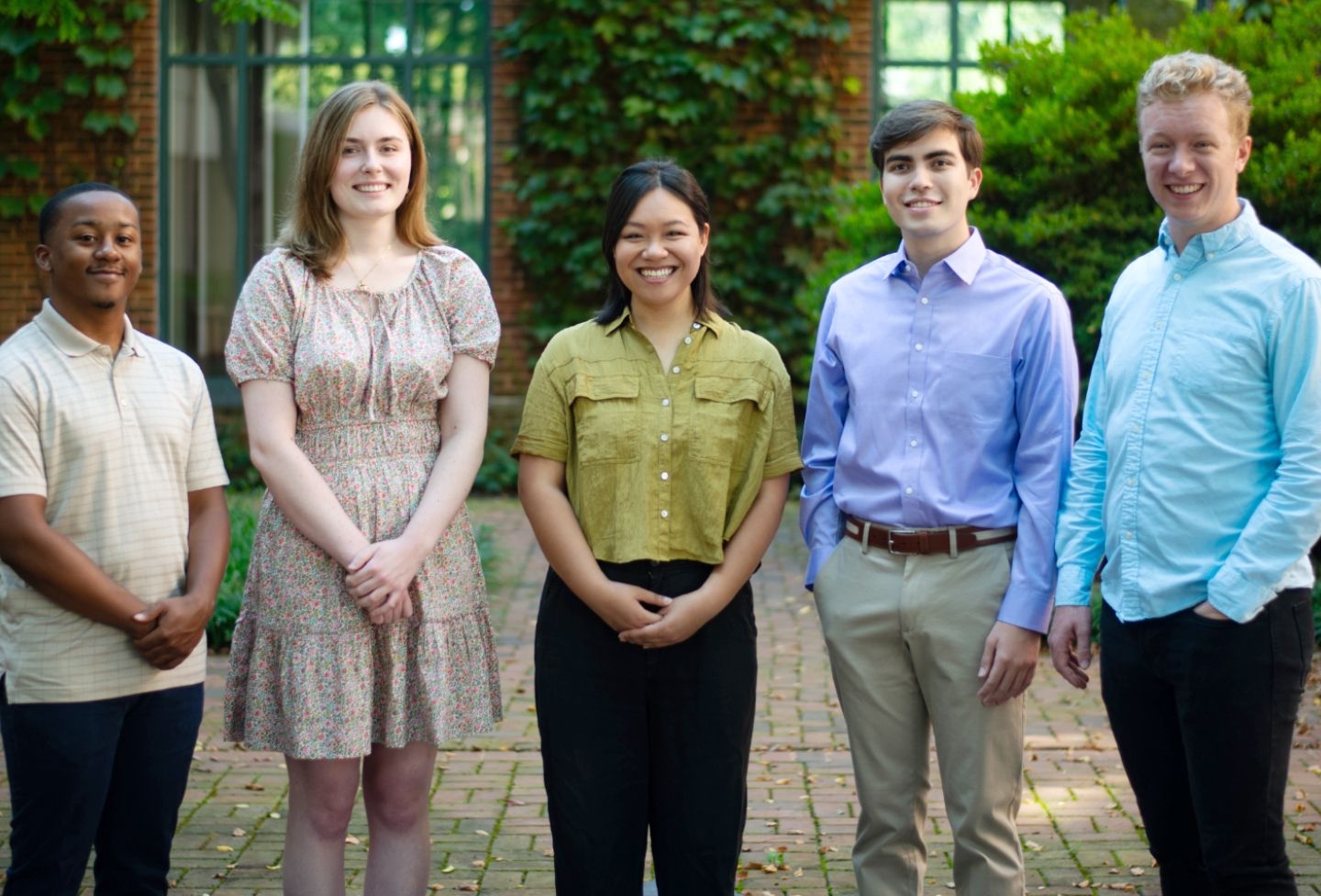

IN THE TWO DECADES since, Jackson has represented numerous current and former professional and college athletes from the U.S. and overseas, including two Olympic athletes. He also represents coaches and the occasional team or athletic organization.

From 1990 to 2014, Jackson volunteered as a baseball, soccer and basketball coach at four different high schools, and he’s taught sports law at Samford University’s Cumberland School of Law since 2012. (When your day starts at 1 a.m., you can fit a lot in.) During the 2021-22 academic year, Jackson was named Cumberland’s Adjunct Professor of the Year.

Living in the heart of the state, Jackson is trapped between rabid Alabama and Auburn fans, but insists that he is still “an ACC guy.” He also acknowledged that working in the field for so long has sapped his interest in rooting for collegiate or professional sports. When he wants to relax, Jackson said he might tune into a UVA lacrosse or Premiere League soccer match, but otherwise, “The fan side of it left for me a long time ago.”

Perhaps that is an inescapable casualty of seeing the darker side of the sports industry, but Jackson treats it as an aspirational outcome.

“I tell the law students I teach that my goal is that my class will change the way that they think,” he says. “And that, from then on, when they go to games, they won’t be watching with a fan’s hat on. They’ll be trying to pick out antitrust violations.”