Now-retired corporate counsel Alfonso Carney Jr. ’74 views his successful career and subsequent public service as stemming from debts of gratitude he owes — to friends, family members, mentors and institutions who helped him along the way.

The barber’s son from Norfolk, Virginia, graduated from the selective Trinity College in Connecticut, taught high school for about a year, then spent three years on scholarship at UVA Law. Here, he worked “harder than I believed possible, and not always with the greatest success.”

But “failure was not an option,” Carney said.

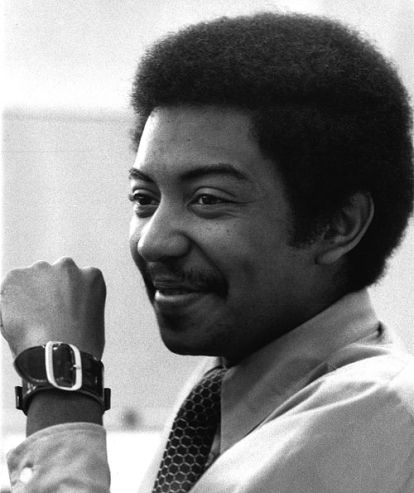

Carney in 1971

He didn’t want to let down his supporters back home, not the least of whom was his “quietly proud” father, whose barbershop was an African-American men’s meeting place. Everyone from doctors to dockworkers would get a haircut there and talk about matters of the day, including civil rights.

Although Carney had helpful professors “and most especially, supportive classmates” on whom he relied at Virginia, he never had a true mentor. For the most part, he had to figure things out on his own.

“I was no one’s protégé,” he said.

But he remembered what his father had often told him: “Son, remind yourself, ‘I didn’t come this far just to come this far.’”

There was a black attorney back home whom Carney greatly admired. With this man as his inspiration, Carney graduated and was ready to practice law, hopefully under his role model’s tutelage.

Unfortunately, the attorney was unable to take on an apprentice at that time.

Carney instead took a legal department job with General Foods in New York — a job made feasible by a black lawyer who had joined the firm six years earlier.

“This man became a mentor who chose to show me the way,” Carney said. It was essential to his success to have found an “advocate and a shield,” he said.

“This black man was putting his own career on the line for me. It worked. In any legal work environment, as a person of color at least, one had to find a mentor, someone who believed in you and your skills enough to provide direction and protection. Decades later, success in large legal organizations is difficult without cultivating a relationship with someone whose opinion matters in the firm, someone whose reputation is fixed and unassailable.”

Carney's son Alfonso Carney III '18 is in the J.D.-MBA program at UVA. Photo by Julia Davis

But Carney didn’t just want to thrive; he wanted to excel. He made the decision to re-evaluate his position every three years. Was he being paid fairly? Was he moving up? Was he challenging himself?

And was he still happy?

“In the companies in which I worked, marketing and finance people were on two- or three-year success tracks,” Carney said. “I adopted that for myself as a lawyer. I would evaluate my successes and failures. Based on evidence, I would make the decision to stay or try to move to something else.”

The approach worked well for building a successful career.

Carney took on various counsel roles after he began with General Foods in 1975. He was senior international counsel when the company was acquired by Philip Morris and then combined with another acquisition, Kraft Foods. He later served as assistant general counsel and assistant secretary of Philip Morris Companies Inc. and corporate secretary of Philip Morris Management Corp.

He retired as vice president and associate general counsel for corporate and government affairs with Altria Corporate Services, an affiliate of Philip Morris USA.

Carney went during his career from being a young man who had never flown to leading legal teams making international deals in Western Europe and in such countries as China, India and Thailand. Before leaving Philip Morris, he had become national counsel for what was then the most powerful corporate lobby in the country.

These days, Carney is busier than ever. Advancement is still on his agenda — albeit now in the interest of public service.

As chairman of the Dormitory Authority of the State of New York, the state’s largest facilities finance and construction authority, Carney has spurred economic growth and helped create new opportunities for minority-owned businesses. In 2017, the authority issued more than $5 billion in bonds, the No. 2 issuer in the nation.

He is also chairman of the New York City Water Board, which sets water and sewer rates with the public interest in mind. Carney chairs public hearings and meets often with groups in the five boroughs.

“We provide a billion gallons of water a day to the people of New York City and beyond, at rates that are fair and equitable,” he said.

Equally close to his heart is educational advancement.

Through his Manhattan-based Rockwood Partners, a company that provides his professional services and those of his spouse on a contract basis, Carney helped the Goldman Sachs Foundation burnish its reputation for altruism. For a brief period as acting chief operating officer and corporate secretary for the Foundation, Carney joined a team that helped promote minority scholarship.

Read More

- The Long Walk: How Gregory Swanson Integrated UVA and UVA Law

- Saying ‘No’ to Wall Street and ‘Yes’ to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund: Elaine Jones ’70

- Black Law Students Mattered: BALSA's Impact

- ‘I Represent All the Students and This Is What I Want’: Linda Howard ’73

- Erasing the Color Line: Ted Small ’92 Looks Back on SUPRA

- The Great Indoors: REI General Counsel Wilma Wallace ’89

- The Jacksons’ Judicial Philosophy: Raymond ’73 and Gwendolyn Jackson ’72

- Generation Next: The Phipps Family

- Standard-bearers: Outstanding Black Alumni

Carney has also served on the boards of his alma maters (and other schools), including the UVA Law School Foundation.

Carney took pride along with other members of the Foundation as the endowment grew over the years. He said he has appreciated being able to provide an important voice on minority concerns. The former chair of the Foundation’s Executive Committee, Carney continues to serve as an honorary trustee and returns to the Law School every spring and fall for board meetings.

Booker T. Washington High School in Norfolk, Virginia, was segregated when Carney attended.

But even with his many accomplishments and extensive public service, Carney’s biggest source of pride is his family. His sister became the first board-certified black female retina surgeon in the country. His wife, Cassandra E. Henderson, is a respected OB-GYN and a professor at the Weill Cornell Medical College. His daughter, Alison Carney, a Mount Holyoke graduate, is a professional musician and singer.

And his son? A graduate of Amherst College, Alfonso Carney III is a student at UVA Law. He is poised to graduate this spring from the J.D.-MBA program.

“One of the proudest moments of my life was when my son decided — on his own, he had options — that he would attend the University of Virginia School of Law and the Darden School of Business,” Carney said. “He has loved being at UVA, and we’ve taken great pride in his success and in something so simple as being able to pay his tuition and fees, which I hope makes it possible for the school to consider scholarships for other minority students.

“Much of what I am I owe to the Law School. It is a debt I shall never be able to repay.”

Why Failure in School Was Never an Option

BY ALFONSO CARNEY JR. ’74

In August 1954, as I turned 6 and prepared for the adventure that would be first grade, my father, a Norfolk barber, took me to the back porch stoop, where he always spoke important words to me.

This time, his words could not have been more frightening. He told me that the High Court — I thought of basketball — had decided in May that white and “Negro” students must be educated together and that I should expect to have white students in my class very soon. I and my sisters had been taught to be wary of whites, that they were often not kind, that they could be dangerous, and that they did not like being stared at, especially their women.

Who were these basketball players who could force me and my friends to go to school with those people?

For weeks in the first grade, I expected to see white students come into my class. When I finally asked when they were coming, my teacher, Miss Reid, said, “Alfonso, not this year.”

I graduated 12 years later with honors from the segregated Booker T. Washington High School. I like to say that often — maybe sometimes too often — I have continued to see the world through race-colored glasses.

As I was entering college, and later law school, failure was not an option. No longer “Negroes,” the black people who nurtured me expected much. I could not let them down. Not the least among them was my quietly proud father, whose barbershop had always been a meeting place for black men in the community, which is still mostly segregated.

These men would get their hair cut, often on a Friday or Saturday night, and chew the fat about the latest black folks to appear on television; hear about recent victims of cancer and the then-mysterious “high blood pressure” (killers in a community of people too often unable to afford reasonable medical care); and hear the opinions of community leaders regarding civil rights, rights believed to be so important they were sometimes referred to as “silver rights.”

During that time, they would also hear from my father about the latest progress of me and my sister, a graduate of Wellesley and Cornell Medical School.