S3 E4: The Wolf at the Door

Economic insecurity is affecting Americans’ lives in profound ways, both at home and in politics. Columbia law professor and UVA Law alumnus Michael Graetz discusses his proposals for reform.

How To Listen

Show Notes: The Wolf at the Door

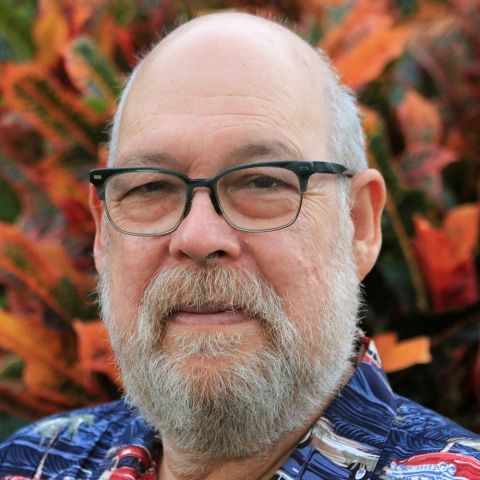

Michael Graetz

A leading expert on national and international tax law, Michael J. Graetz joined the Columbia Law School faculty in 2009, after 25 years at Yale Law School, where he is a professor of law emeritus and a professorial lecturer. He has written on a wide range of tax, international taxation, health policy and social insurance issues. His recent scholarship, including his 2016 book, “The Burger Court and the Rise of the Judicial Right” (with Linda Greenhouse of The New York Times), has focused on U.S. legal history and problems around economic inequality. His latest book, “The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and How to Fight It” (with Ian Shapiro), proposes realistic policy solutions and strategies to make individuals and communities more secure.

In addition to his academic career — which has included teaching posts at the University of Southern California and the University of Virginia School of Law — Graetz has held several positions in the federal government. He was assistant to the secretary and special counsel for the Department of the Treasury in 1992, and deputy assistant secretary for tax policy at the Department of the Treasury from 1990 to 1991.

Graetz has been invited to testify as an expert witness on a variety of tax matters before U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means and the Senate Committee on Finance. His many honors include being elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and being chosen as a John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Fellow. In 2013, he was awarded the National Tax Association’s Daniel M. Holland Medal for lifetime achievement in the study of the theory and practice of public finance.

Graetz received his J.D. from the University of Virginia School of Law and his B.B.A. from Emory University.

Listening to the Show

Transcript

“WE WORK AGAIN” - WPA, 1937

OLD-TIMEY NARRATOR: “Only a few years ago, we were a discouraged people.”

LESLIE KENDRICK: Economic insecurity is not new in this country. This Depression-era audio makes that clear.

OLD TIMEY NARRATOR: “We struggled vainly to regain our bearings while depression, fear and failure stalked the nation.”

RISA GOLUBOFF: But over the last few decades, a new wave of economic anxiety has been building. As jobs disappear, unions weaken, and the safety net frays, the American worker is living an increasingly precarious and inequitable existence.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Eighty-five years ago, Roosevelt’s solution was the New Deal, a slew of laws and programs designed to address this economic insecurity.

OLD TIMEY NARRATOR: “It changed the haggard, hopeless faces of the breadline, into faces filled with hope and happiness. For now, we work again!”

RISA GOLUBOFF: But what can the law do TODAY to help restore equity in our economy and allay this growing anxiety? That’s what we’ll be discussing in this episode of Common Law.

THEME MUSIC IN, THEN UNDER

RISA GOLUBOFF: Welcome back to Common Law, a podcast from the University of Virginia School of Law. I’m Risa Goluboff, the Dean

LESLIE KENDRICK: And I'm Leslie Kendrick, the Vice Dean. In this season of Common Law, we're looking at issues connected to law and equity.

RISA GOLUBOFF: In our last episode, we talked with UVA law professor Naomi Cahn about how the many benefits associated with marriage are driving inequity for the increasing number of Americans who choose not to marry.

NAOMI CAHN: If you look at the people who are most likely to get and to stay married, that's higher income, higher education. And that's been a huge change.

BRING MUSIC UP, THEN UNDER

LESLIE KENDRICK: If you missed that episode, we hope you’ll check it out.

Today, we’re zooming out to talk about economic inequality in general — the kind that affects the married and unmarried alike.

THEME MUSIC OUT

RISA GOLUBOFF: Michael Graetz is the author of many books on economic inequality, including Death by a Thousand Cuts, The Fight over Taxing Inherited Wealth, and The Burger Court and the Rise of the Judicial Right. He's currently a professor of tax law at Columbia University and an emeritus professor at Yale Law School. He's also a former professor and a graduate of UVA Law School. Welcome, Michael.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Thank you, Risa. Thank you, Leslie. It’s good to see you both!

LESLIE KENDRICK: Michael, we’re so happy to talk with you today, and part of what we’re excited about is your new book which you co-wrote with political scientist Ian Shapiro, and it's titled The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and How to Fight It. So I want to start with just a basic question: who or what would you say is the “wolf” at the door?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: The wolf at the door is the fear, anxiety, and concern that is legitimately experienced by millions and millions of American families because of their fundamental economic insecurity. They no longer have faith that they can maintain good-paying jobs and the consequences of that are devastating to families across America.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So this is in contradiction to this long-held, I don't know if you would call it a myth or a reality that used to exist that Americans can pull themselves up by their bootstraps, right? And that the next generation will be better off than the last.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Yes.

RISA GOLUBOFF: What is it that has changed over time?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Well, in the period after the Second World War …

BRING MUSIC IN (Glenn Miller & His Orchestra: “String of Pearls”)

MICHAEL GRAETZ: … the U.S. had all the money there was. China was entering into a dark communist period, Europe and Japan were in shambles. And so for the two decades following the war, we had really widely distributed economic growth with labor unions and a very robust manufacturing sector.

FADE MUSIC OUT

“FORD TECHNIQUE FOR TOMORROW," CLEVELAND, BROOK PARK, 1954

“What has been done here in Cleveland sets the pattern for future industrial progress. For more than an engine is being built here. This is a new way of industrial life. It is still early morning in America, dawn of a new day in industry.” (music swells)

BRING MUSIC IN (Audioblocks - “Flying Me High”)

MICHAEL GRAETZ: In the 1970s, that all began to change. Imports of textiles and cars and steel, especially from Germany and Japan in particular began to hollow out the U.S. manufacturing base. And what we've now seen is a culmination of many decades now of a decline in those kinds of jobs, especially for people who don't have college degrees or higher. And so the situation has really dramatically deteriorated for so many Americans.

LESLIE KENDRICK: In our last episode, we were talking with Naomi Cahn about the “family wage” and how through the mid-20th century, there were many long-term jobs available that didn’t require a college education, but ably supported an entire family and even provided benefits. That’s not an expectation that most people have today, when they may have to move from job to job, and when there’s only a frayed safety net to catch them in between.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It’s important, I think, to realize that when we think about graduates from the University of Virginia or Columbia, the fact that they're going to have to change jobs 12 or 15 times over a lifetime, many of them view that as an opportunity. It's not really a challenge. But when you take a middle-aged man or woman who has only a high school education, who's been working for a number of years, becoming unemployed is really devastating, not only to their way of life economically, but also psychologically. In the home, you see things like domestic abuse and the like increasing. So this is really a deeper problem. And your comment about the safety net is extremely important. We just don't have a good safety net in the United States.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So all of that is why in your book you choose purposefully to discuss economic insecurity rather than economic inequality, right?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Yes.

RISA GOLUBOFF: And by that, I take it you mean that the harm lies not only in the economic gap between the haves and the have-nots but in the absolute condition of living with such economic insecurity which is not only a psychological problem, as you’ve just described, but ultimately also a political one.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Exactly. So as you know well, the Democratic party has been focused on what Bernie Sanders likes to call the millionaires and the billionaires.

“A THREAT TO AMERICAN DEMOCRACY," 2014

BERNIE SANDERS: “Madam president, there is one family in this country — the Walton family, the owners of Walmart — who are now worth, as a family, $148 billion dollars. That is more wealth than the bottom 40% of American society.”

BRING MUSIC IN HERE (Soundstripe: “Hero’s Theme”)

MICHAEL GRAETZ: And I don't disagree — just to be clear — with those who say that millionaires and billionaires could be paying more taxes. I just don't think that increasing taxes on the wealthy alone is going to solve the problems of economic insecurity.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Could you tell us a little bit about the specific policy recommendations that you put forth in the book?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: The principle recommendations that we make are to create jobs. We are clear that only the government can address these fundamental problems, which is the reason that we focus as much as we do on infrastructure.

RISA GOLUBOFF: And by infrastructure, you mean not just roads, bridges and railways .. but also broadband — talking about the digital divide.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: We know from the pandemic, broadband access has become really essential across the country.

LESLIE KENDRICK: What else do you propose?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: We urge proposals like the minimum wage and increasing the earned income tax credit, to make work pay better. And we focus on child care, mainly through universal pre-K, but also through child care programs that have been quite successful around the country. This is a way to enable adults in the family to be able to work without worrying about how their children are doing during the workday.

RISA GOLUBOFF: You also write about the importance of health insurance, which is, understandably right now, top of mind for a lot of people during a pandemic.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: We now see just how precarious it is to have health insurance provided by your employer so that when you lose your job, you also lose your health insurance. And the pandemic has really made that unmistakable.

FADE MUSIC OUT

LESLIE KENDRICK: One aspect of it that you touched on was wage stagnation, and in the time period that you're talking about, the minimum wage has really not changed. What explains that?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Well, for some reason, the Republican party in particular, just stopped raising the national minimum wage. We've recently seen increases in states and localities, but the federal minimum wage hasn't been changed now in nearly 20 years. And it's obviously below a wage that would provide a living standard for a family that would be adequate.

RISA GOLUBOFF: Yeah, you write about the “fight for $15,” which is a largely Democratic push to raise the current federal minimum wage from $7.25 an hour to $15 dollars an hour.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Yes, that’s right.

LESLIE KENDRICK: That sounds like a big increase to a lot of people, but you cite a study that says a worker has to earn even more than that — $17.14 an hour — just to afford a one-bedroom rental.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: There is a big problem with wages at the bottom, but I just want to be clear that this problem moves way up from the very bottom, well into the middle-class. And focusing on the minimum wage is important, but either way we need to do more for people who are above the poverty level, even though we do need to do a lot for those who are at the poverty level.

RISA GOLUBOFF: One piece I have to imagine is close to your heart with your roots in tax, is the earned income tax credit, which you mentioned a little bit earlier, but maybe you could say a little bit more about now.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: The earned income tax credit has really been the best benefit for moving working people out of poverty, particularly working people with children. It is a refundable tax credit that people get if their wages don't exceed a certain amount. It has had a long history of bipartisan support.

RONALD REAGAN - TAX REFORM ACT REMARKS, OCT. 22, 1986

PRESIDENT REAGAN: “It’s also the best anti-poverty bill, the best pro-family measure, and the best job creation program ever to come out of the Congress of the United States.”

PRES. CLINTON’S REMARKS ON THE EARNED-INCOME TAX CREDIT (1998)

PRESIDENT CLINTON: “It has also been responsible for much of our strong progress in reducing child poverty.”

OBAMA ANNOUNCES BIPARTISAN DEAL TO EXTEND EXPIRING TAX CUTS, DEC. 7, 2010

PRESIDENT OBAMA: “The earned income tax credit that helps families climb out of poverty.”

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It was originally proposed by a Republican administration, and it was increased by George Herbert Walker Bush and by Bill Clinton. And I think there is now in the Congress growing recognition of the need to further modernize it and also to expand child credits, to make credits for families with children more refundable than they are now. That would lift a lot of people out of poverty.

LESLIE KENDRICK: So obviously, the earned income tax credit only helps if you’re earning an income. What about people who are unemployed?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: For that, we really look to a major revision of unemployment insurance.

BRING MUSIC IN (Audioblocks: “Over the Horizon”)

MICHAEL GRAETZ: When our book was published in February 2020, unemployment in the United States was the lowest it had been in 50 years, and now it's the highest that it's been in 90 years. And that's due to the pandemic and many of those jobs are not coming back. And it has been extremely difficult to get Congress to focus on unemployment and the gaps in unemployment insurance. If we had a sound system of unemployment insurance, Congress could have built on that. And what we saw during the CARES Act was the need to create, out of whole cloth, a temporary system of unemployment insurance.

FADE MUSIC OUT

RISA GOLUBOFF: Part of the reason that you say that was necessary was because states haven’t traditionally provided unemployment insurance to folks who are freelancers or independent contractors. And as more and more Americans move into gig work, that’s a big gap.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: And there has been a race to the bottom in the states in unemployment insurance, so that you have states like Florida that had been covering 11% of unemployed workers. Nationally, it's less than a third who are covered. And so, what we now need is a national program of unemployment insurance.

LESLIE KENDRICK: But that sounds like a heavy lift. In your book, you talk a lot about the necessity of building coalitions to lobby for the changes that you’re recommending — that’s one of the “building blocks” that you say is essential to getting big legislation passed. But that seems particularly difficult when it comes to unemployment insurance, because who comprises the coalition to fight for that?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It's very difficult to have a coalition that will focus on unemployment insurance, because most people who will be unemployed don't think of themselves as the “future unemployed.” They think of themselves as the future retirees of America and so the American Association of Retired People is one of the most powerful and important legislative powerhouses in the nation. But there is no American Association of the Future Unemployed, nor should we expect one. So here, you really have to find political leadership, which is one of our other building blocks that will move this issue forward.

RISA GOLUBOFF: You wrote about some early political leadership in this area that failed under President Kennedy. Say more about that.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: In addition to the failures of unemployment insurance, the Kennedy administration began a program, which it called trade adjustment assistance. Trade adjustment assistance was enacted in the 1960s just when the U.S. was beginning to open up its borders to imports and free trade was beginning to get on the agenda of the U.S. political system.

JFK’S ADDRESS IN MIAMI AT THE OPENING OF THE AFL-CIO CONVENTION, DEC. 7, 1961

PRESIDENT JOHN F. KENNEDY: “We need a program of retraining our unemployed workers. All of you who live so close to this problem know what happens when technology changes and industries move out and men are left. And unless — and I’ve seen it in my own state of Massachusetts, where textile workers who are unemployed, unable to find work, even with new electronic plants going up all around them — we want to make sure that our workers are able to take advantage of the new jobs that must inevitably come as technology changes in the 1960s.”

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It's a program that has been a total failure for lots of reasons, not the least of which is that it's very hard to prove that you lost your job because of trade rather than something else. And so we propose a program that we call unemployment adjustment assistance, which is designed to provide a path and support to people moving from unemployment to reemployment, including — if important to the worker — money to move his or her family to a place where job opportunities are more robust.

BRING MUSIC IN (Soundstripe: “Up Above”)

LESLIE KENDRICK: So I'm from the mountains in eastern Kentucky, an area of the country that has been subject to many different efforts to try to alleviate poverty and poverty has remained stubbornly existent there. And it seems like there are some parts of the country where it's been difficult to create sustainable new economic initiatives and the infrastructure mostly functions to help people get out, to get to other places. And that's not always a realistic possibility for everybody because people have family ties and other types of ties that keep them in a given area …

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Yes.

LESLIE KENDRICK: … and I'd love to hear your thoughts about how to try to spread economic prosperity across all the nooks and crannies of the United States.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Well, it's a tough problem and I think one of the reasons we've seen such a stark rural/urban divide in the American political system is that most of the economic growth in this nation in recent years has come out of the urban centers and not out of rural areas like eastern Kentucky. I think in terms of infrastructure, we really have to think broadly about broadband and internet access because in a rural area like eastern Kentucky at best the internet is spotty and slow. But if the broadband were as good in eastern Kentucky as it is in Vietnam, to take an example, the workers there would have opportunities that they don't now have, but it will require education and it will require infrastructure.

FADE MUSIC OUT

LESLIE KENDRICK: So there's a song by Dwight Yoakam who’s from the next county over from me in eastern Kentucky, that’s called “Route 23,” that says you learn reading, writing, and route 23, which is the road out of town, and I always thought, but I don't want to have to leave in order to have a job or to have some prospects. I didn't want to do that, and I think there are a lot of people today who don’t want to do that either.

“ROUTE 23” BY DWIGHT YOAKAM

They learned reading, writing, Route 23

To the jobs laying waiting in those cities' factories

They didn't know that that old highway

Could lead them to her misery

MICHAEL GRAETZ: But you're still in Charlottesville, Virginia, which is pretty nice country.

LESLIE KENDRICK: That's right.

RISA GOLUBOFF: You’ve written about how it important is for people to be educated, to be mobile, to be willing to take on service jobs, and that song and Leslie’s story really underscores that. But there’s a gender issue to that as well, right?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: There is a form of, what in the old days would have been called ‘masculine pride.'

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION MODERN STEEL MAKING PROMOTIONAL FILM

NARRATOR: “Men in the rolling mill. Men at the electric arc furnace. Men who are proud to be called “steel men.”

MICHAEL GRAETZ: That limits, I think, the willingness of lots of white American middle-class men to take on jobs in sectors like education and health care, which have been growing dramatically — service sectors. And so I'd like to see more opportunities being accepted in places like that.

BRING MUSIC IN (Soundstripe: “Fading Light Instrumental”)

RISA GOLUBOFF: In your book, you say that the one transformation in our political process that you think would be most effective in combating economic insecurity would be resurrecting private-sector labor unions. Now, back in the ’50s, about 40% of private-sector workers belonged to unions, and now that’s down to about 6%. So why is that important? Why focus on unions?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: The decline of labor unions has not only affected workers’ wages, but it has dramatically reduced the ability of the average worker to have a say that is effective in state or federal legislatures. And this is due to a whole series of legislative and judicial changes. So the decline of unions has been going on for a long time.

RISA GOLUBOFF: One of the things that you point out in your book is that at the same time unions have been growing weaker, businesses have begun playing a much more important role in getting legislation passed.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: The role of business interests is much more important politically in getting anything done than it was historically. They are an important source of finance for political campaigns, but they also have the ear of their representatives because they're the ones who are the job creators, to borrow a phrase. And they know their representatives from their local communities where they both work and live. And so I think it's hard to make the kinds of changes that we've been proposing without the support of business.

LESLIE KENDRICK: And do you have a sense of whether businesses would support your proposals?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Each of the proposals in the book, the earned income tax credit, for example, enjoys business support for lots of reasons, but it increases the wages of their workers and the money is coming out of the government's pocket, not theirs. And I think that the proposals that we make from moving from unemployment to reemployment are also something that the business community can be engaged in.

RISA GOLUBOFF: What about the courts, Michael? During the New Deal era, when FDR was pushing for a lot of government programs designed to boost the economy in the midst of the depression, he faced a lot of pushback from the courts.

THE MARCH OF TIME: THE SUPREME COURT APPROVES THE WAGNER ACT

NARRATOR: “At his second inaugural, the president again faces the chief justice of the court, which upheld only 2, ruled out 11 of his New Deal laws as unconstitutional …”

RISA GOLUBOFF: So I’m curious … If the coalitions you talk about do come together and pass the kind of comprehensive legislation you think is necessary, how do you think that legislation is likely to fare in the Roberts court, if it gets that far?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Well, that's a great question, Risa. Several years ago, I guess it's now 20 years ago, Jerry Mashaw, a colleague of mine at Yale, and I wrote a book called “True Security.” We urged an individual mandate for health insurance purchases and a robust subsidy through tax credits to people who couldn't afford the health insurance.

LESLIE KENDRICK: That sounds familiar!

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It looks a lot like what we now know as Obamacare. And it had never occurred to us that there was an issue under the commerce clause with providing that kind of universal health insurance.

NATIONAL FEDERATION OF INDEPENDENT BUSINESS V. SEBELIUS, OPINION ANNOUNCEMENT, PART 1, JUNE 28, 2012

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: In these cases, we consider claims that Congress lacked constitutional power to enact two provisions of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: In fact, it had been proposed at that time by the Heritage Foundation on the right. We were shocked that there were five votes in the Supreme Court that would have said that Obamacare violated the Commerce Clause. And now there may be six votes. This is a very cramped reading of Congress' ability under the Necessary and Proper Clause to provide legislation that gives workers the kinds of economic security that we need.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: The Court today rules that Congress does not have the power under the Commerce Clause to enact the individual mandate. The Court goes on to rule that Congress does have such power under the taxing clause.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: So I am a little concerned about that. Although I have to say, I don't believe that a national program of unemployment insurance — to take an important example that we've talked about before — is under the same kind of threat today from the court that it would have been during the New Deal. But I do think that the lesson out of the Obamacare litigation is that the legislature needs to be very careful to protect that kind of legislation from a court that may want to take us back in time.

BRING MUSIC IN (Audioblocks: “Multitudes”)

LESLIE KENDRICK: You make a compelling case for all of these programs — boosting the minimum wage, rethinking unemployment assistance, tax credits, health care, child care — but what do you think the chances are that any of them will actually come to pass?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: If you ask me what the biggest hurdle is to that kind of change, it is the incredible short-term vision or lack of long-term vision of our political representatives. I think if the Trump administration has taught us anything about politics, it has taught us that legislators are far more concerned about their own reelection than they are about really digging into and solving these kinds of problems for the American people. And so I’m hoping that with the leadership of business, with some political leadership, and with community leadership, people organizing — if not through labor unions, in other ways to have a voice — that we can make some of the changes that we regard as so important and so very, very urgent to help the American worker and their family.

LESLIE KENDRICK: One thing that we've been asking all our guests this season is what's your version of the promised land. What does true economic security look like to you?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: The clock can't be made to run backwards. And so, I think what we need to do is think about how to get people retrained to be able to participate in an economy where technology is going to be more and more important, and job security is going to be precarious going forward.

FADE MUSIC OUT

RISA GOLUBOFF: I have one last question that we've been asking all of our guests. So, the season we're calling “Law and Equity.” And you talk in the book about your shift in focus from equality to insecurity, or equality to security, and I'm curious if equity — does it resonate with you, or do you think, it doesn't really apply in this area?

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It would be very difficult for me, having taught tax courses for all of those years, to throw equity overboard. I spend a lot of time on equity in the classroom and in my writing, including in this book. It's all about equity. It's all about fairness. Not only opportunities, but also in outcomes. And I think if there is one silver lining to a horrible, horrible, horrible pandemic, it is that it has really brought to the surface the economic insecurity of American workers and their families, something that we were trying to do in our book. That’s now unmistakable. And so the challenge is to build an equitable society where people are not resentful, anxious, and fearful about their own economic security, and are therefore are willing to take into account the issues that affect their community and their nation — issues that are so important.

RISA GOLUBOFF: Well, thank you so much, Michael. This was really an amazing conversation.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: It was fun.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Thank you so much.

MICHAEL GRAETZ: Go Hoos!

LESLIE KENDRICK: Yes! (laughing)

BRING THEME MUSIC IN, THEN UNDER

RISA GOLUBOFF: That was Columbia University’s Michael Graetz, a tax law expert and author of “The Wolf at the Door.”

BRING THEME MUSIC UP, THEN UNDER AND OUT

LESLIE KENDRICK: Well, this might just be me, but I really enjoy talking with tax scholars. And Michael Graetz is such an amazing scholar of tax and so much else that I feel as though I just learned an enormous amount, both about issues facing our country and possible solutions to them.

RISA GOLUBOFF: I agree completely. I mean, Michael is a giant in the world of tax law scholarship and he has devoted himself and his career to thinking about distribution and redistribution in taxation. He’s really thought about the role of tax in the larger economic structures of our country and in the context of economic inequality.

LESLIE KENDRICK: His focus on economic insecurity, I think is really important and something that I think deepens and enriches our focus this season, because it's not just about how things look relatively speaking; it's about how folks are doing in absolute terms. And in absolute terms, too many Americans are struggling and face lots and lots of different forms of precarity in their lives.

RISA GOLUBOFF: People are not saying, “I feel economically insecure, or I don't have the economic power I think I ought to because I'm not the 1%,” they're looking at people who are much more closely aligned to them in their life circumstances and asking “why don't I have what they have?”

LESLIE KENDRICK: Yeah.

RISA GOLUBOFF: In the conclusion to the book, he and Ian Shapiro talk about these experiments with monkeys. If an experimenter asked a monkey to do a task and gave the monkey a piece of cucumber, they were totally happy until they saw that the monkey next to them was getting a grape for doing the same thing. And then they went crazy and they were so upset. And what he points out is the monkey didn't care that the experimenter had lots of cucumbers or lots of grapes because that wasn't the right comparator for the monkey. And so we didn't talk that much about politics, but when we talk about the politics of resentment, when we ask about this political moment that we're in, I think that the way that Michael and Ian Shapiro are thinking about what economic insecurity does and who one is comparing themselves in terms of the inequality, is really a critical part, not only of the economic story, but also the political story.

LESLIE KENDRICK: It is really interesting to think about how politics and economics are combined here and that’s not the first time that we’ve seen that theme over the course of this season, and I think it probably won’t be the last.

BRING THEME MUSIC UP, THEN UNDER

LESLIE KENDRICK: That’s it for this episode of Common Law. If you’d like to learn more about Michael Graetz’s work on economic insecurity, visit our website, Common Law Podcast Dot Com. You’ll also find all our previous episodes, links to our Twitter feed and more.

RISA GOLUBOFF: We’ll be back in two weeks with Melissa Murray of the New York University School of Law, talking about the limits of what the law can do when it comes to lifting social taboos, and the backlash that can result.

MELISSA MURRAY: 2015, you have Obergefell where we have same-sex marriage being legitimized formally, but we’ve seen in the aftermath, the rise of these religious accommodation claims which I think you can imagine as another kind of regulatory displacement playing out.

RISA GOLUBOFF: We’re excited to share that conversation with you. I’m Risa Goluboff.

LESLIE KENDRICK: And I’m Leslie Kendrick. See you next time!

CREDITS: Do you enjoy Common Law? If so, please leave us a review on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher — or wherever you listen to the show. That helps other listeners find us. Common Law is a production of the University of Virginia School of Law, and is produced by Emily Richardson-Lorente and Mary Wood.