Photo by Dan Addison/UVA Communications

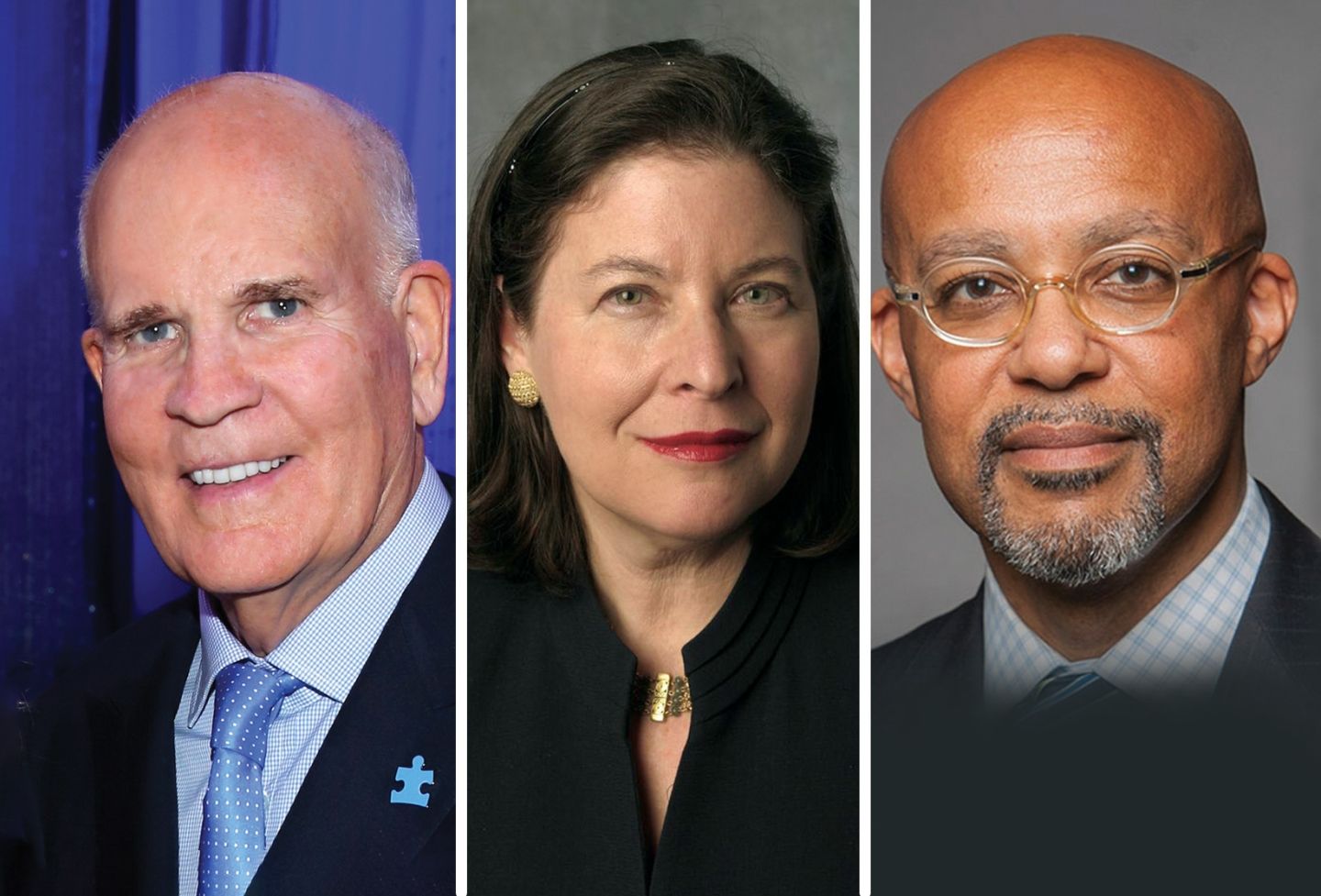

26. John Warner ’53

Serving Virginia, Protecting the Nation

John Warner ’53 served five terms as a Republican U.S. senator — becoming the second-longest-serving senator from Virginia. As chairman of the Armed Services Committee, he helped beef up the nation’s military while simultaneously boosting Virginia’s economy via its military installations and shipbuilding companies.

He also served on the Environment and Public Works Committee, the Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions, and the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence.

Warner’s significant legislation included being a co-sponsor of America’s Climate Security Act of 2007, which proposed a market-based “cap and trade” approach to dealing with the greenhouse gas emissions associated with climate change.

He was also an important voice in deterring future torture and abuse in the war on terror, arguing that violations of the Geneva Conventions by the U.S. can only harm American prisoners in the future.

Even before he entered elected office, Warner was protecting the nation and its military. His signature accomplishment as U.S. secretary of the Navy was executing the U.S.-Soviet Incidents at Sea agreement. The 1972 pact forged by Warner and his counterpart, Soviet Navy Commander-in-Chief Fleet Admiral Sergey Gorshkov, instituted provisions to avoid unintended naval engagement between the two superpowers — and to avoid escalation in the instance of encounter.

Warner rose to secretary after being appointed undersecretary by President Richard Nixon. He previously served in the Korean War as a Marine.

He also was once married to actress Elizabeth Taylor. Today, he is a senior adviser to Hogan Lovell and married to Jeanne Vander Myde.

A. E. Dick Howard in the mid-1970s. UVA Law Special Collections

27. A. E. Dick Howard ’61

Constitutional Framing in Virginia and Abroad

Professor A. E. Dick Howard ’61 joined the faculty in 1964. Four years later, he was asked to be part of the team that would provide a much-needed update to Virginia’s fundamental legal language — its Constitution.

The 11-member Virginia Commission on Constitutional Revision included famed civil rights attorney Oliver W. Hill; future U.S. Supreme Court Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr.; two former Virginia governors, Albertis S. Harrison Jr. ’28 and Colgate W. Darden Jr. (the latter of whom was also a UVA president); and Hardy Cross Dillard ’27, who was the Law School’s dean from 1963-68.

Howard served as executive director. His role was primarily as a draftsman to the commissioners, he said.

“My appointment,” he recalled. “was not anything I had planned. My good fortune was to be around at the right time.”

There was much to fix from the previous constitutional overhaul in 1902. Poll requirements that disenfranchised black voters and mandates for public segregation had been rendered moot by federal civil rights legislation — but these stains on history still needed to be removed. The constitution was likewise a mess in terms of its length and organization.

“The old constitution was a hodgepodge,” Howard said. “Not only that, it was racist and populist.”

Other issues the commission addressed in the revision, pared down to a svelte 18,000 words (half the length of its predecessor), included fairness with school funding, partisan gerrymandering and the environment.

Howard served as counsel to the General Assembly as it refined and approved the final recommended language.

“The legislature made further changes,” he said. “They actually made some improvements. I was a skeptic when I went down to Richmond, but I was impressed with how the General Assembly rose to the occasion.”

But even with the blessing of both Virginia houses, his work wasn’t done. Gov. Linwood Holton asked Howard to lead the referendum campaign for the new constitution’s approval by the people.

It was a daunting request. He had no experience running a campaign, yet he knew the subject better than anyone. What he didn’t know was who or what he would be up against. “How will the political winds blow?” he asked.

Howard traveled across the state, speaking to any group that would have him, sometimes three or four times a day. He enjoyed using his gift for public speaking, which was part practice, part genetics. He had an uncle who was an evangelical preacher.

“I had to go out and talk to farmers and workers and all kinds of folks,” he said. The experience helped refine his pitch, because “they asked common-sense questions.”

Although he hadn’t polled public sentiment, he predicted significant opposition. And he was right.

One flyer depicted Howard leading a voter, drawn as a mouse, into a giant mousetrap; it warned of loss of local government control. A conspiracy theory floating around in southern parts of the state was that the change would impose forced school busing.

It helped Howard’s cause that he had friendly locals, such as county sheriffs, introduce him wherever he visited. He also studied the past mistakes of other states that had attempted constitutional revisions and failed. Instead of a “take it or leave it approach,” the revisions went on the ballot as four separate questions.

In 1971, the ballot items each passed by votes of 63 percent or greater. The ballot item containing the main body of the Constitution passed by 72 percent.

Howard said a core argument probably made the difference. With so many Virginia state laws under challenge, “rewriting the Virginia Constitution was a way for Virginians to take control of public affairs in their own hands.”

His success in the drafting and with the ratification campaign, along with his growing national visibility as a constitutional expert and commentator, led to new opportunities in the 1990s with the fall of the Soviet Union.

“I found myself getting invitations to work with post-Communist countries,” he said. “What a God-given moment, to be at the elbows of drafters in foreign capitals. Not having been able to be in Philadelphia in 1787, this was not a bad second-best.”

To date, Howard has “compared notes” with revisers of constitutions in Brazil, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Romania, Russia, Albania, Malawi and South Africa.

28. Harold Marsh ’66

Prominent Civil Rights Attorney

Harold Marsh ’66 was a managing partner in the noted Virginia law firm Hill, Tucker & Marsh. He was a civil rights attorney, substitute judge and mentor to youth in his community before he was gunned down at a Richmond intersection in 1997, apparently by a disgruntled man facing eviction by one of Marsh’s clients.

Marsh “battled racial discrimination in employment and successfully forced Virginia to adopt single-member legislative districts, opening the door to the election of more African-Americans to the General Assembly,” the Richmond Free Press reported in 2016.

That year, the general district courthouse in South Richmond was named the Henry L. Marsh III & Harold M. Marsh, Sr. Manchester Courthouse.

Henry Marsh, his brother, was also a managing partner at Hill, Tucker & Marsh and a state politician who served in the Virginia Senate and as Richmond’s mayor.

Hill, Tucker & Marsh changed names over the years but maintained a storied history of fighting for the civil rights of its clients, beginning in the era of Jim Crow.

Terry with Gov. Douglas Wilder during her swearing-in ceremony. AP Photo/Steve Helber

29. Mary Sue Terry ’73

First Woman Elected to Statewide Office in Virginia

The first woman elected to statewide office in Virginia was Mary Sue Terry ’73, in 1985. Terry was the second woman to serve as attorney general of any U.S. state, serving two terms. She successfully argued eight cases before the U.S. Supreme Court. She negotiated the recall of 13,000 defective Ford ambulances, and her office also notably convicted the controversial political activist Lyndon LaRouche for mail fraud, conspiracy to commit mail fraud and tax evasion.

Before serving as attorney general, she was a member of the Virginia House of Delegates and an assistant commonwealth’s attorney in Patrick County. She is a former president of the National Association of Attorneys General.

30. Angela Ciolfi ’03

30. Angela Ciolfi ’03

A Voice for Indigent Justice

Angela Ciolfi ’03, a champion for the rights of the indigent, is director of the Legal Aid Justice Center in Charlottesville. Her recent work includes advocating against Virginia’s practice of suspending driver’s licenses when residents owe court fines they cannot pay. Ciolfi has litigated significant cases in the Supreme Court of Virginia and the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Through her previous work directing the center’s JustChildren program, she fought successfully to require public schools to publish suspension and expulsion data broken down by race, gender and disability, and to roll back so-called “zero tolerance” suspension policies.

Continue: 5 Business Leaders, 5 General Counsel, 5 in Investing, 5 in Law Firms

More Change Agents

- 100 Change Agents: A Completely Incomplete List of UVA Lawyers Who Changed the World

- 5 Who Fought for Rights

- 5 in Criminal Law, 5 in Government Service

- 5 in International Law, 5 Military Leaders

- 5 Business Leaders, 5 General Counsel, 5 in Investing, 5 in Law Firms

- 5 Nonprofit Leaders, 5 Educational Leaders

- 5 Who Were There To Make a Difference

- 5 Best-Selling Authors

- 5 in Sports, 5 in Entertainment

- 5 in a League of Their Own

- 5 From the Early Days, 5 Firsts

- 5 Who Changed UVA