S2 E5: The Lowdown on Libel

The Supreme Court took on New York Times Co. v. Sullivan in 1964, in part, to protect the civil rights movement. But did justices go too far in making libel hard to prove? UVA Law professor Frederick Schauer explains new concerns.

How To Listen

Show Notes: The Lowdown on Libel

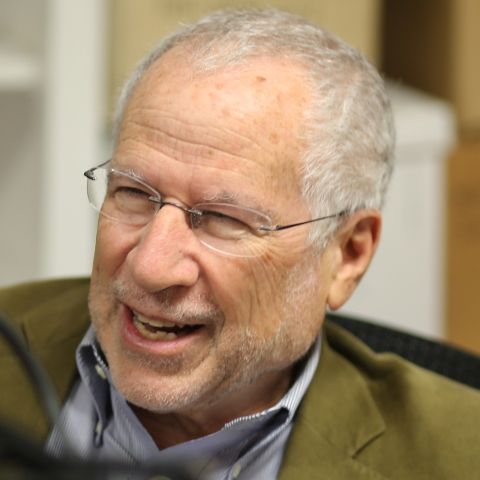

Frederick Schauer

Frederick Schauer is a David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law at the University of Virginia. From 1990 to 2008 he was Frank Stanton Professor of the First Amendment at Harvard University, and was previously professor of law at the University of Michigan. He has been visiting professor of law at the Columbia Law School, Fischel-Neil Distinguished Visiting Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, Morton Distinguished Visiting Professor of the Humanities at Dartmouth College, distinguished visiting professor at the University of Toronto, visiting fellow at the Australian National University, distinguished visitor at New York University, and Eastman Professor and fellow of Balliol College at the University of Oxford.

A fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship, Schauer is the author of “The Law of Obscenity,” “Free Speech: A Philosophical Enquiry,” “Playing By the Rules: A Philosophical Examination of Rule-Based Decision-Making in Law and in Life,” “Profiles, Probabilities, and Stereotypes,” “Thinking Like a Lawyer: A New Introduction to Legal Reasoning,” and, most recently, “The Force of Law.” The editor of Karl Llewellyn, “The Theory of Rules,” and a founding editor of the journal Legal Theory, he has been chair of the Section on Constitutional Law of the Association of American Law Schools and of the Committee on Philosophy and Law of the American Philosophical Association. In 2005 he wrote the foreword to the Harvard Law Review’s annual Supreme Court issue, and has written widely on freedom of expression, constitutional law and theory, evidence, legal reasoning and the philosophy of law. His books have been translated into Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Chinese and Turkish, and his scholarship has been the subject of three books and special issues of Jurisprudence, Law & Social Inquiry, Ratio Juris, Politeia, the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy, and the Notre Dame, Connecticut and Quinnipiac Law Reviews.

Listening to the Show

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan

- Libel

- Seditious libel

- Chilling effect

- Common law countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, South Africa, Hong Kong and more)

- “Make No Law: The Sullivan Case and the First Amendment,” by Anthony Lewis

- Justice Clarence Thomas calls for reconsidering New York Times in his concurring opinion for Kathrine Mae McKee v. William H. Cosby Jr.

- Associated Press v. Walker (the Supreme Court ruling that applied libel law to public figures as well as public officials)

- Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (struck down a Florida law granting a right to reply to political candidates who had been attacked by newspapers)

Transcript

[MUSIC PLAYING]

RISA GOLUBOFF: Hello, and welcome to Common Law, a podcast from the University of Virginia School of Law. I'm Risa Goluboff, the dean.

LESLIE KENDRICK: And I'm Leslie Kendrick, the vice dean. What better topic to bring us back from our winter break than a lawsuit that had it all-- media, politics, civil rights, and libel.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: It started in 1960. The New York Times published a paid advertisement entitled "Heed Their Rising Voices."

LESLIE KENDRICK: This is UVA law professor, Frederick Schauer, discussing the dispute that led to the landmark United States Supreme Court case, New York Times vs. Sullivan.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: It was an ad basically objecting to the way that Martin Luther King and others had been treated in the late 1950s South, in particular, in Alabama.

[AUDIO PLAYBACK]

MARTIN LUTHER KING: Just because she refused to get up, she was arrested.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: The advertisement talked about police abuse.

MARTIN LUTHER KING: You know, my friends, there comes a time when people get tired of being shackled [INAUDIBLE].

[END PLAYBACK]

FREDERICK SCHAUER: It talked about various things that the police had done to Dr. King and some number of others in Montgomery, Alabama, and it turned out that Commissioner Sullivan, who was in charge of the police, possibly took umbrage at what the ad said. So Sullivan sues the New York Times for $500,000. Back then--

LESLIE KENDRICK: Commissioner LB Sullivan argued in an Alabama state court that the times ad was libelous, because it had factual errors and damage to his reputation, the key elements in a libel claim. After deliberating for just two hours, the jury decided the Times was liable for libel and awarded Sullivan half a million dollars.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

RISA GOLUBOFF: But Schauer says this particular case was not your garden variety libel dispute, and Sullivan's defamation claims were tenuous at best. For one, Sullivan had not even been named in the advertisement, and the factual errors it contained were fairly trivial. But in the Deep South, at the height of resistance to desegregation, it was clear the lawsuit had an ulterior motive-- targeting civil rights protesters and allies of the movement.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: The real goal here was to punish the New York Times not for publishing this ad, but basically for representing, let us say, Northern Yankee agitators who were interfering or criticizing the South, and just at the beginning of that part of the civil rights era that was characterized by marches, protests, demonstrations, picketing, and the like.

RISA GOLUBOFF: And that, Schauer says, worried the justices, who had only recently struck down school segregation in Brown vs. Board of Education.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: We don't exactly know why the Supreme Court took the case, but we have a pretty strong suspicion that they took the case largely as a way of protecting the civil rights movement, more than out of an overriding concern for free speech. But because libel law was a matter of state law, the only way that there could be a federal constitutional hook was indirectly through the claim that this was a violation of the First Amendment. If it had been any other kind of libel case, it's very unlikely that the Supreme Court, at least at the time, would have taken it.

LESLIE KENDRICK: So spoiler alert-- the New York Times ultimately won this case. And while that outcome aided the fight for racial equality in the 1960s, it also had far reaching and unexpected consequences for libel law that we're still living with today.

RISA GOLUBOFF: That's right, Leslie. And as you might have guessed, considering how this season of Common Law is all about the power of law and lawyers to change history, we're going to talk about some of those consequences and ask whether they're entirely a good thing. So let's get back now to our interview with Fred Schauer. We asked him to explain how the Supreme Court justified hearing the case at all and why it reached the decision it did, given that before all this, the Court had over and over again ruled that libel was not a First Amendment issue.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: So part of the arguments that the Court ultimately accepts is that this looks like the common law crime of seditious libel. That is it looks like the common law crime of criticizing the government, trying to undercut the government, and the like. This is for all practical purposes, not an ordinary libel suit. This is the equivalent of the state bringing an action against the newspaper, even though it's technically civil and not criminal, looks like seditious libel, looks like a bunch of other things that the court had done in the First Amendment area, at least from the 1930s up until 1964.

LESLIE KENDRICK: So it looks like some form of censorship and some form of punishment of criticism of the government--

FREDERICK SCHAUER: Yes, exactly.

LESLIE KENDRICK: --that directly implicates First Amendment principles.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So what happened when the case reached the Supreme Court?

FREDERICK SCHAUER: So the Supreme Court goes through, as is common, they go through eight different drafts of an opinion. Justice Brennan writes-- ultimately writes an opinion for the court. What turns out to be the Court's opinion is his eighth draft. Some justices wanted absolute immunity. Some justices wanted merely minor shifts in the common law.

Ultimately, what they agreed on is a dramatic constitutionalization of the common law of libel. The opinion decides that when public officials sue for libel, it is necessary for them, for the public official, to prove by clear and convincing evidence that what was said about the official was false. And much more significantly-- he calls it actual malice-- was known to be false by the publisher at the time it was published.

The Court also says, maybe there can be liability in cases of what it calls reckless disregard, but it made clear just a couple of years after that, that even reckless disregard required actual knowledge of possible falsity and refusal to go ahead in the face of that. So the short answer is, after this case, public officials can bring libel suits only if they can prove by clear and convincing evidence that this was knowing falsity.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So it's a huge sea change.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: It's a huge sea change. As a practical matter, it is almost impossible to prove that. You have to show that some-- not just that it was negligent, not just that it was grossly negligent in common law sense of grossly negligent, but somebody knew something was false or knew something was probably false and published anyway. It turns out it's not only a sea change in the doctrine.

It's a sea change in the relationship between libel law and political debate and political campaigns. With very few exceptions, New York Times versus Sullivan, at least from 1970, once all the kinks had been worked out, from 1970 until now, with very few exceptions, has essentially eliminated the libel suit as a weapon or a component of political campaigns and political debates and political arguments.

That is dramatically different from what we see even in industrialized, liberal, open democracies in the rest of the common law world. In Australia, in New Zealand, in Canada, in the United Kingdom, political figures are commonly suing newspapers. They are commonly suing each other. New York Times has essentially ended that in the United States.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So would you say that the Court swung too far in that direction, and that if it was initially too easy to win a libel suit, if the Court made it too hard now?

FREDERICK SCHAUER: So before we get to what I think, which matters less--

RISA GOLUBOFF: I think it matters a lot.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: --it turns out the Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United Kingdom, and every other country in the common law world, and most of the countries in the civil law world thought it had swung too far. Journalists talk to each other, and, therefore, journalists throughout the world know about this opinion. They have urged their local supreme courts or the equivalents to adopt a rule similar to the New York Times vs. Sullivan actual malice rule, and every court that has considered the issue has said, no, that goes too far.

They've changed a little bit. The common law in the countries I've just mentioned has changed a little bit. Now it's necessary to show negligence or, in some other way, departure from journalistic standards. But to require that a plaintiff, in a case like this, show actual intentional falsity, people in other countries think it's too far.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So before we get to your own views, what's their reasoning? Why do they think it's too far? What are the values on the other side that they want to protect?

FREDERICK SCHAUER: One of them, so the New York Times vs. Sullivan is the birth in the US of what's commonly called the chilling effect. That is New York Times vs. Sullivan is based on the idea that if newspaper publishers are afraid of liability, they will be overly cautious, hypercautious, refrain from publishing things that are, in fact, true. That's the chilling effect. In many other countries, they've recognized the chilling effect, but they've recognized the exact opposite chilling effect.

That is, they have said, if it is impossible for public officials to have any redress for blatantly false things said about them, people are not going to go into public life. This will chill public spirited citizens from going into public life, running for public office, or at least that's what lots of common law countries think.

LESLIE KENDRICK: So one thing about this-- and you've written a really important article about the chilling effect and many other things that touch on the chilling effect-- it's one thing to see that there's a chilling effect, or at least there's the potential for chilling. Of course, it's really hard to measure a chilling effect, because you can't see the speech that's not being produced. But it's another thing to figure out what the precise remedy is.

And so the Court thinks that there is a chilling effect, and it introduces the actual malice standard as the remedy for that. And a lot of other countries would say, it's not obvious that that was the right remedy. Even if there is chilling, there are all these other concerns, and you'd have to take all those concerns into account. And they seem to think the common law scalpel way of doing that is better than the kind of U.S. Supreme Court blowtorch way of dealing with the whole problem.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: Right. I think that's right. And for example, there are countries that say maybe there should be mandated retractions, impermissible under American constitutional law. Maybe there should be the opportunity for someone who is libeled to have equal print space to respond. Florida tried something to that effect 15 years after New York Times vs. Sullivan. The Supreme Court struck it down.

So there are potential remedies other than eliminating libel actions for all practical purposes that other countries have used, none of which would fly in the U.S. It's also worth mentioning at this point that one of the important effects of New York Times vs. Sullivan came three years later, when the Court said, recognizing that labor leaders, religious leaders, corporate leaders, and so on also have an effect on public affairs. The Court said, again, possibly too broadly, possibly too heavy handedly. All of the New York Times vs. Sullivan principles apply to public figures as well as public officials.

The Court did not and has never said that there is a difference between the public figure who is involved with matters of public or political or policy importance and any other public figure. So it turns out that the same legal regime that applies to Commissioner Sullivan-- presidents, senators, governors, and so on-- also applies to Tom Brady, Miley Cyrus, Paris Hilton, and various other celebrities, who have little, if no connection with public affairs or public matters.

RISA GOLUBOFF: So would you change that? Would you recreate a distinction between public officials and public figures?

FREDERICK SCHAUER: I would change that. Interestingly, the most important book about New York Times vs. Sullivan was written by the late New York Times columnist, Tony Lewis. He would have changed it as well. Despite being, in general, enthusiastic about a broad and strong First Amendment, he would have changed that. And when the Court finally addressed the issue in Curtis Publishing vs. Butts, Justice Harlan would have changed that as well.

One can understand the idea of the chilling effect. One can understand some of the issues involved, but still say, well, maybe public figures who have no connection with public policy at all and whose entire profession is tied up in their reputation, maybe they should be slightly more able to bring a lawsuit than public officials and various others who occupy those kinds of positions.

Perhaps more significantly, recently in the wake of concerns about fake news, in the wake of concerns about the way in which falsity can spread so rapidly in an era of the internet, in an era of social media, and so on, the number of people otherwise sympathetic with the First, Amendment otherwise sympathetic with the press, have now begun to suggest that, yes, maybe New York Times has gone too far, even with respect to public officials. And we have to ask ourselves the question now, what's the real problem? Is the real problem excess chilling of the newspapers, or is the real problem excess proliferation of falsity?

10 years ago, a lot of people, including me, would have said, the real problem is excess chilling of the newspapers. 10 years later, I'm not sure. And I think a lot of other otherwise free speech, first amendment, press sympathetic people are so worried about the rampant proliferation of flat-out factual falsity, not just reasonable differences of opinion about political programs, but flat out demonstrable factual falsity that the suggestion is increasingly being made that some variety of negligence standard, rather than the strict intentionality of New York Times vs. Sullivan might now be appropriate.

LESLIE KENDRICK: At the same time that that's happening, though, you have President Trump, who, on the campaign trail and since, has said, he wants to open up libel law, as he puts it, to make it easier for people like himself to sue outlets like the New York Times. And we have Justice Thomas who wrote a separate opinion recently suggesting that maybe New York Times should be re-examined. So the political valence of this is complex, and there are people who might otherwise agree about very little who kind of overlap in their interest in rethinking the New York Times.

But I think from a journalist's perspective, there may be more concern than ever, and they would point to Trump statements or Thomas to say, this is precisely the wrong time to start thinking about giving the government more ability to regulate truth and falsity. How do you think all that cashes out?

FREDERICK SCHAUER: OK. Well, I mean you put it the way some number of press enthusiasts would put it.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Right.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: That is when the president suggested that libel law ought to be changed, it appeared, from what he said, that he believed that this was a matter of legislation rather than a matter of Supreme Court doctrine.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Well, that, too. Yeah. Yes.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: So the quick jump from a remedy in a court for damages to the government is doing the restricting might be a little too quick. Justice Thomas, at least, in this one opinion, isn't suggesting so much that there ought to be a dramatic change as this ought to be worked out in common law fashion. And although I disagree with him, one of the things that might be said in his favor is without the interjection of the First Amendment or constitutional considerations, countries like the UK and Australia and New Zealand in common law fashion have substantially changed the traditional common law of libel to make it much more press protective than it used to be, much more concerned about chilling than it used to be, all in common law fashion without going as far as the Supreme Court did in New York Times vs. Sullivan.

There is a hint in this one opinion from Justice Thomas that that's really what he wants. Continue to working this out in common law fashion. Now that doesn't mean that if there were a change, there wouldn't be problems. There would inevitably be more suits brought by political officials. There would inevitably be more political campaigns in which libel suits going in both directions came to become at the center of political campaigns and the like. That's not such a good thing. Indeed--

RISA GOLUBOFF: Have those things happened in Australia and other countries?

FREDERICK SCHAUER: Australia commonly, New Zealand commonly, UK commonly, but a little bit less now, South Africa rampantly. Libel suits have been a big part of South African political life, even since 1995, in the end of apartheid. So one wonders about all of this, one wonders about what political campaigns would look like, that looks like it would be problematic.

On the other side would be the argument, well, maybe it would make political figures a little bit more cautious about throwing around specific factual allegations about their opponents that they couldn't actually establish. Whether we would have better political campaigns with, let's put it bluntly, more truth is the question. Or if not more truth, at least less straight out falsity.

RISA GOLUBOFF: Thank you so much for being with us, Fred.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: Thank you.

RISA GOLUBOFF: This was a great conversation.

FREDERICK SCHAUER: This was fun. This was great. Thank you.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

LESLIE KENDRICK: That was Frederick Schauer, David and Mary Harrison Professor of Law at UVA. He's the author of numerous articles and books, including Free Speech: A Philosophical Inquiry, The Law of Obscenity, and Thinking Like a Lawyer.

RISA GOLUBOFF: That was fabulous, Leslie. These are things you think about all the time, but for me, it was a real treat to hear about all the pros and cons and all the complexities of libel law and its interactions with the First Amendment.

LESLIE KENDRICK: It's so great to talk with Fred about this. He has written on every aspect of this, and so many of them are really important. It was really fun that we got to talk about a number of them-- the actual malice standard and whether that's the right remedy or not. There's just so much there. And it was also fun to get to talk about it with you, where all of this really is coming out the civil rights context.

It's such a civil rights case. That's really what's going on. And yet it winds up having these enormous first amendment implications, just completely changing the relationship between libel law and constitutional law. And in some ways, we backed into this because of this really problematic situation that comes out of the civil rights era.

RISA GOLUBOFF: I think that's true for so much, both--

LESLIE KENDRICK: Yes.

RISA GOLUBOFF: --outside of libel context, within the First Amendment context, and then in criminal laws, more generally so the place where I know it best, obviously, is in, you know, low level criminal laws like vagrancy, loitering, disorderly conduct, breach of the peace, where during the same period, the court kept hearing those cases, because those were the laws under which many of the civil rights protesters were arrested.

This is one data point among many, both within the First Amendment and beyond, where the cases that the court was deciding in the 1960s were really so heavily influenced-- "determined" may be too strong-- but so heavily influenced by what was going on in the civil rights movement, and also especially how the states of the Deep South were using their various kinds of state power to suppress civil rights protests and challenges to Jim Crow that made the court and made lawyers think creatively about how to attack that state power and I think made the court very hyperaware, that if they weren't to intervene, it would be very hard for anyone to intervene.

LESLIE KENDRICK: That seems exactly right. There's this enterprising nature to the way law is being used within the Deep South, so I think about Alabama's use of their own foreign corporations law to try to force the NAACP to disclose its membership lists, which will thereby open those members to reprisals by third parties and attacks by vigilantes. There's just a lot that's going on.

RISA GOLUBOFF: And that also comes up to the Supreme Court, and the Supreme Court is protective of those lists and those members and makes new law there on a right to association.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Creates whole new first amendment doctrine there, too, in order to address this problem. And one possible story one could tell about this says, the lengths to which the Supreme Court will go to avoid calling Alabama racist straight off, right? Avoid saying, this is an abusive and animus-based use of your foreign corporations law. Instead, they create an entire effects-based inquiry into these types of applications of law that suggest, well, sometimes these are going to chill people's right of association. And we're not we're not say anything bad about anybody. We're just saying, sometimes the effects are going to be too unfortunate.

RISA GOLUBOFF: As I was just saying, the Court is one of the few actors that has power to intervene in what are often state or local battles between civil rights protesters and state and local governments that have all the cards, right? And there's no voting for African-Americans in the South at this time. They don't have political power. And so the Court-- and this is true, I think, often of the stories we tell about Brown vs. Board of Education as well as and NAACP vs. Alabama.

In all of these cases, the Court is situated as the hero. And yet there's an irony there, because the reason why, after the Civil War and after the reconstruction amendments, African-Americans are eventually stripped of their political power is because the court allows it to happen. And the court essentially abdicates its responsibility in the late 19th century, and the early 20th century allows segregation to arise, allows for disenfranchisement, allows for involuntary servitude of all kinds.

And then come the middle of the 20th century, lo and behold, there's no political power. It's very hard for African-Americans to contest the enormous powers of the state, and happily, the Court does jump in eventually in the 1950s, the 1960s. But it's solving a problem of its own making from almost a century before.

LESLIE KENDRICK: That takes me back to our conversations with Cynthia Nicoletti and the way the law was used by Southern landowners to try to reclaim their land and to take it back from newly freed slaves, which just gets to law being a part of all of these stories and legal decisions that are made, in one century, having enormous implications for the legal landscape a century later.

RISA GOLUBOFF: Yeah, so how law changed the world, and then changed it again, and changed it again, and changed it again.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

So Leslie, I was struck as we were talking with Fred. It's not that we haven't had common law topics before on the show, but we were really using the phrase, "common law," quite a lot to distinguish it from constitutional law. And that just tickled me.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Yeah, yeah. This is really common law, Common Law today.

RISA GOLUBOFF: Exactly.

LESLIE KENDRICK: Yeah. Well, that's it for this episode of Common Law. We hope you'll join us next time for more stories about when law changed the world.

RISA GOLUBOFF: In the meantime, let us know what you think. Rate or review us on Stitcher, Spotify, Apple Podcast, or wherever you hear the show, and check out our website, CommonLawPodcast.com, to find all our past episodes, including last season's shows about the future of law. Background information on this episode and much more. You can also follow us on Twitter, @commonlawuva.

LESLIE KENDRICK: We'll be back in a couple of weeks with our next guest, Joyce White Vance. She'll be talking about criminal law reform and its impact on prosecutors.

JOYCE WHITE VANCE: The question that I increasingly began to ask is, is what we are doing here making our community safer?

RISA GOLUBOFF: Common Law comes to you from the University of Virginia School of Law. Today's episode was produced by Sydney Halleman, Robert Armengol, and Mary Wood , with help from Virginia Caine. The show was recorded at the studio of the Virginia Quarterly Review. I'm Risa Goluboff.

LESLIE KENDRICK: And I'm Leslie Kendrick. See you next time.