5 From the Early Days

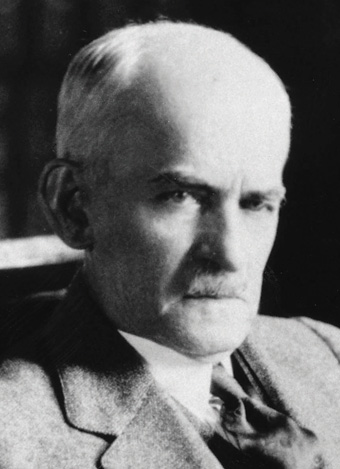

86. William Minor Lile 1882

86. William Minor Lile 1882

The First Dean

William Minor Lile 1882 was the Law School’s first official dean, a role he served in from 1904-1932. During that time, he secured funding for the school’s homes — first Minor Hall, named after his great uncle and alumnus Professor John B. Minor 1834, then Clark Hall. He strengthened the school’s academic credentials by shifting the course of study from one to three years, and pushed the Virginia General Assembly to require a college degree before students could attend (a task not fully accomplished until 1939, when F.D.G. Ribble ’21 became dean). Near the end of Lile’s tenure, a moot court competition was established; in 1962 it was renamed the William Minor Lile Moot Court competition.

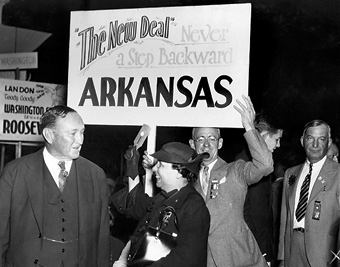

87. Joseph Taylor Robinson 1895

Assisted New Deal Legislation

Joseph Taylor Robinson 1895 was a governor of Arkansas, and a U.S. senator and congressman from his home state. He supported progressive reforms, including the right for women to vote. As the Senate majority leader under President Franklin D. Roosevelt from 1933-37, he helped shuttle Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation.

88. Arthur J. Morris 1901

The Man With the Plan

You may know Arthur J. Morris 1901 as the namesake of the UVA Law Library. But did you know Morris was the first to extend widespread consumer credit in the United States via a system of banks?

Morris Plan Banks, established in 1910, provided an alternative to pawnbrokers and loan sharks for low- and moderate-income individuals. The noncollateralized loans helped many borrowers establish themselves or get through tough times. The plan also pioneered automotive financing and credit life insurance.

“Every day I meet people who say my father and my grandfather got started with the Morris Plan,” Morris told The New York Times in 1971, at age 90.

Three out of five people in the U.S. borrowed from a participating bank during the Great Depression, Morris told the newspaper.

At the plan’s peak, just before World War II, 176 lenders participated in the network.

The idea of installment credit was nothing new. For decades, companies had sold their products to buyers who couldn’t pay in one lump sum. Yet higher-ticket items, such as houses and cars, were harder to come by for the economically challenged. Likewise for them, the cost of starting a business could be daunting, the impact of a catastrophic family illness too much to bear financially.

Morris provided a solution in the absence of collateral. Requiring a steady job and co-signers of similar earning power, along with satisfactory answers to some questions concerning stability and character, proved to be a successful formula.

While there were early critics of the credit plan, just as there are of credit today, relatively few borrowers defaulted, according to the Law School’s Special Collections, which houses Morris’ papers. Morris argued that most people in the early century were eager to be debt-free, in contrast to the modern maxed-out consumer.

When he applied to the Virginia Corporation Commission to charter his first bank, Morris’ idea was strange and rife for rejection.

“I have carefully considered your application for a charter for your hybrid and mongrel institution,” Judge Robert R. Prentiss, the chairman of the commission, wrote in response to the charter request. “Frankly, I don’t know what it is. It isn’t a savings bank; it isn’t a state or national bank; it isn’t a charity. It isn’t anything I ever heard of before. Its principles seem sound however, and its purpose admirable. But the real reason that I am going to grant a charter is because I believe in you.”

On April 1, 1910, the bank opened, backed by $20,000 of Morris’ own money and additional funds from associates, according to the Law Library.

The credit boom was born.

Courtesy Library of Congress, Harris and Ewing Collection

89. Alben Barkley 1902

The ‘Veep’ Who Could Give a Speech

Among the great orators to have studied at UVA Law, Vice President Alben William Barkley 1902, who attended during a summer session (after having already passed the bar in Kentucky), was particularly known for his rousing speeches that could leverage change.

First elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1912, Barkley was a leading figure in creating the Prohibition Amendment and the Volstead Act. He was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1926, and assisted Senate Majority Leader Joseph Taylor Robinson 1895 in passing much of the New Deal legislation. Barkley became majority leader after Robinson’s death.

Barkley might have been a vice presidential candidate in 1944, which would have led to his ascension to the presidency, but a fiery speech critical of President Franklin Roosevelt’s administration earlier that year ruined his chances, according to the UVA Miller Center of Public Affairs’ website.

Sen. Harry Truman of Missouri got the nod, and subsequently became president upon Roosevelt’s death.

At the end of the term, when it came time to run officially for the highest office in the land, Truman wanted Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas as his running mate, but Douglas declined.

Truman tapped Barkley, who proved his fealty. The two stumped aggressively, giving whirlwind speeches across the country that very likely made a difference in the close race. Contrary to the famous gaffe headline in the Chicago Daily Tribune, Truman indeed defeated New York Gov. Thomas E. Dewey in 1948.

“Both Truman and Barkley campaigned vigorously and pulled off one of the most stunning upsets in the history of American politics,” the Miller Center states.

Perhaps fittingly for someone so oratorically inclined, Barkley died in 1956 from a heart attack during an impassioned speech he gave at Washington & Lee University.

“I would rather be a servant in the house of the Lord than to sit in the seats of the mighty,” he uttered before collapsing.

Reed presented the Law Library and its director, Frances Farmer, with its 100,000th volume in 1953. Photo courtesy UVA Law Special Collections

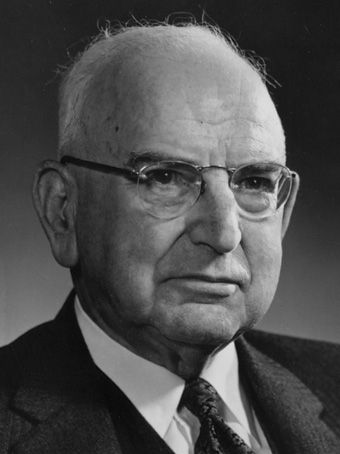

90. Stanley Forman Reed 1908

The New Deal Defender’s Ascent to the Supreme Court

Stanley Forman Reed 1908, who studied law at the University of Virginia but did not obtain a law degree, was an associate justice at the Supreme Court from 1938-57. In that capacity, he played a key role in numerous cases, including those affecting racial justice. He wrote the majority opinion in Smith v. Allwright, which struck down a Texas law requiring would-be voters in Democratic primaries to be white in order to cast a ballot.

Lesser known are his efforts that helped pull the nation out of the Great Depression.

As general counsel of the Reconstruction Finance Corp. under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Reed supported the administration’s monetary policies following the Crash of 1929.

The ability to redeem deflated paper money for gold at its pre-Depression value was causing a run on U.S. gold reserves. Roosevelt pulled the nation off the gold standard, and asked the Reconstruction Finance Corp. to purchase gold at an inflated cost.

Congress, in tandem, voided clauses in public and private contracts that permitted gold to be redeemed.

Creditors sued, and Reed assisted the attorney general with written and oral arguments in Norman v. Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Co., defending the legality of the government’s actions.

The successful outcome resulted in Reed’s subsequent appointment as solicitor general, where he continued to defend New Deal policy, and in his later nomination to the Supreme Court.

“In 1935, Reed became solicitor general of the United States at a time when several of FDR’s New Deal programs were being challenged in the high courts,” according to a UVA Law Library biography of Reed. “As a result, Reed once argued six major cases before the Supreme Court in a two-week period. Although Reed lost several of these early cases, by 1937 he secured major victories in several cases, including the Supreme Court’s upholding of minimum wage laws, the National Labor Relations Act and the taxation power of the Social Security Act.”

Virginia educated two future justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. The other, James Clark McReynolds 1884, wrote the dissent in the Gold Clause Cases, and was part of the “Four Horsemen” bloc that worked to strike down New Deal programs. McReynolds was nicknamed “Scrooge” by a journalist because of his infamous temperament.

5 Firsts

91. John Charles Thomas ’75

91. John Charles Thomas ’75

Poetic Justice

Retired Justice John Charles Thomas ’75 was the first African-American to ascend to the Supreme Court of Virginia. He did so in 1983, a year after becoming the first black lawyer to make partner at an “old line” Southern law firm, the former Hunton & Williams.

Thomas is currently a partner with Hunton Andrews Kurth and a judge of the Court of Arbitration for Sport in Lausanne, Switzerland, which handles cases involving violations of the World Anti- Doping Code for all Olympic Sports, the Tour de France, FIFA and the LPGA.

He is also a poet who has recited his own works at Carnegie Hall.

92. Cynthia Kinser ’77

92. Cynthia Kinser ’77

Hail to the Chief

Cynthia Kinser ’77 served as the first female chief justice of the Supreme Court of Virginia, from 2011- 14. She began as a justice on the court in 1998. Earlier in her career, she was elected as Lee County’s first female commonwealth’s attorney, in 1980.

93. Cleo Powell ’82

93. Cleo Powell ’82

Serving Justice

The first female African-American justice to serve on the Supreme Court of Virginia, Cleo Powell ’82 assumed office in 2011 and continues in that role. She has served as a judge at every level of Virginia’s judicial system.

94. Karl Racine ’89

94. Karl Racine ’89

D.C. Attorney General

Karl Racine ’89 is the first independently elected attorney general of the District of Columbia.

Earlier in his career, in 2006, he became the first black managing partner of a top-100 law firm, Venable. He also served as associate White House counsel under President Bill Clinton.

95. Sean Patrick Maloney ’92

95. Sean Patrick Maloney ’92

True Representation

Serving in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2013, Sean Patrick Maloney ’92 is the first openly gay person elected to Congress from New York.

More Change Agents

- 100 Change Agents: A Completely Incomplete List of UVA Lawyers Who Changed the World

- 5 Who Fought for Rights

- 5 in Criminal Law, 5 in Government Service

- 5 in International Law, 5 Military Leaders

- 5 Virginia Voices

- 5 Business Leaders, 5 General Counsel, 5 in Investing, 5 in Law Firms

- 5 Nonprofit Leaders, 5 Educational Leaders

- 5 Who Were There To Make a Difference

- 5 Best-Selling Authors

- 5 in Sports, 5 in Entertainment

- 5 in a League of Their Own

- 5 Who Changed UVA