UVA Lawyer profiles leaders and scholars in higher education and explores how the Law School prepares graduates to excel in the field.

5 LEADERS

The Champion

The Champion

University of California President Janet Napolitano ’83 Rises to Support Undocumented Students

The Transformer

The Transformer

Taylor Reveley III ’68 Helped Transform William & Mary’s Law School, Then the Entire College

The Motivator

The Motivator

Stanford Law School Dean M. Elizabeth Magill ’95 Has Made Her Mark by Getting Things Done

The Diplomat

The Diplomat

Through Deanships at George Washington and Wake Forest Law Schools, Blake Morant ’78 Offers Wisdom

The Inspirer

The Inspirer

Harvard’s Jim Ryan ’92 Connects With Students and Alumni Through Words and Actions

5 SCHOLARS

5 SCHOLARS

Forging a Path for Leaders in Legal Education

5 Ways UVA Law Preps Graduate and Faculty to Excel in Academia

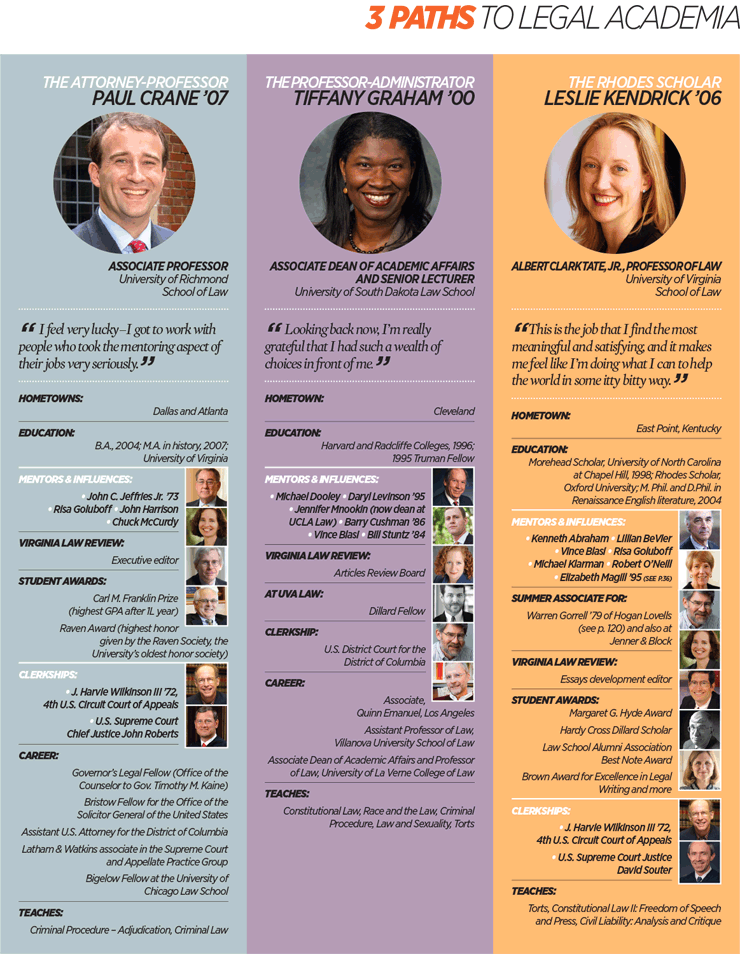

Leslie Kendrick ’06 was studying and teaching Renaissance English literature at Oxford University on a Rhodes scholarship when she realized she wanted to go to law school.

“One thing I really appreciated about law was that it was a really big tent,” she said. “You never knew where that degree was going to take you.”

Kendrick’s path through law school, and those of her colleagues and fellow faculty members, offer a map to understanding how the school helps develop interested students into academics, and faculty into leaders in their fields. The key landmarks of the journey include opportunities to write and clerk, mentoring and support from faculty, the camaraderie of the student body, and the faculty’s commitment to fostering a stimulating intellectual community.

More than 250 alumni are law professors or teach as adjuncts at law schools nationwide. Faculty who started their careers at Virginia have become leading thinkers at Harvard, Stanford, Yale, Columbia, Chicago and more.

“Students and faculty both find that our commitment to the scholarly endeavor is not only about learning and expanding minds intellectually, but about offering a network of support beyond that,” said Dean Risa Goluboff. “To name just a few examples, we read and critique each other’s work, we offer advice about the job market, and we model good citizenship by being available to one another and seeking input and dialogue from colleagues of diverse viewpoints.”

1. The Write Journey

Though Kendrick wasn’t sure she would go into teaching again, all signs pointed to a future faculty post. She took classes that allowed her to concentrate on writing, and learned from her professors, including Kenneth Abraham, Vince Blasi (now at Columbia), Lillian BeVier and Michael Klarman (now at Harvard). She had “enormous amounts of support from lots of people.” During her first winter break, she dug through old microfiche while researching for Klarman, and also later conducted research for Goluboff’s first book “The Lost Promise of Civil Rights,” winner of the 2010 Order of the Coif Biennial Book Award and the 2008 James Willard Hurst Prize.

“I was pretty proactive in finding opportunities to write and everyone was very encouraging of that,” she said. She wrote papers on her own, including “A Test for Criminally Instructional Speech,” which was published in the Virginia Law Review and submitted by Elizabeth Magill ’95 (now Stanford Law School dean, see p. 36) for the Brown Award, a $10,000 national prize for excellence in student legal writing. (Kendrick won the award in 2006.) Kendrick wrote papers with faculty, including Julia Mahoney, Abraham and Greg Mitchell. A paper written for a class with former Dean Richard Merrill won first place in the Food and Drug Administration’s student paper competition and was published in the Food & Drug Law Journal.

Though her work was recognized, Kendrick said she “was writing not with a view to publishing it, but with the view of practicing it.”

After law school she clerked for Judge J. Harvie Wilkinson III ’72 on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. She was invited back to give a job talk — and soon was hired. (She was later offered a clerkship with U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Souter and deferred teaching a year.)

“I could not have been luckier,” she said. “It was just a dream come true.”

2. A Clerkship Ladder and a Degree Ahead

In addition to the many ways the school offers practice with writing and research, it also provides critical support for clerkships, said Professor Micah Schwartzman ’05 (College ’98), who plays a critical role at the Law School in advising students seeking clerkships and careers in academia.

Virginia is ranked fourth among law schools in the number of clerks it sends to the U.S. Supreme Court, and also is fourth in federal clerkship placement for the Classes of 2013-15, according to American Bar Association data.

“We have one of the strongest clerkships programs in the country,” he said. “Clerkships serve as stepping stones to lots of different types of career paths, but they’re very important for many people coming into legal academia. They learn a lot about the legal process during that time.”

Schwartzman also clerked on the Fourth Circuit, for Judge Paul V. Niemeyer, after graduation.

“It was a privilege to clerk, especially in the Fourth Circuit,” Schwartzman said. “I had a wonderful mentor in Judge Niemeyer, who placed great emphasis on the importance of communicating clearly through reasoned opinions. More generally, there are few opportunities after graduation that provide so much exposure to the legal process and to such a wide range of legal issues. For those considering legal academia, it is an especially valuable experience.” Schwartzman said clerkships often help graduates position themselves for the faculty job market, which involves shaping a portfolio of writing samples and presenting an academic profile.

Aside from clerkships, another path potential professors take is studying for an additional graduate degree, “because they need time to write,” he said. “In recent years, Virginia has hired faculty with Ph.D.s in legal history, philosophy and economics. Advanced degrees are not required, and there are different paths to academia. But at this point, all of those paths require extensive research and writing.”

3. The Wind at Your Back

University of Richmond associate professor Paul Crane, who earned a B.A. (2004) and J.D. and M.A. in history (2007) at UVA, said several professors encouraged him in his eventual pursuit of academia. On his way to his current role, he worked as a Bristow Fellow, as an assistant U.S. attorney for the District of Columbia, as a clerk for U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts, and as an appellate associate at Latham & Watkins.

Throughout, he said, a cadre of professors supported him.

“You feel like you have the wind at your back when you have the level of support that I had from my professors at UVA,” he said, crediting former Dean John C. Jeffries Jr. ’73, Dean Risa Goluboff, law professor John Harrison and Professor Chuck McCurdy of the History Department and Law School.

Crane wrote his first law review article under McCurdy’s wing; Jeffries offered detailed comments on his job talk paper and counseled him on going into academia; he worked as a research assistant for Goluboff, a “wonderful, supportive cheerleader for me throughout my career,” and learned lessons about history not being inevitable; he was impressed by Harrison’s deep respect for the law and how he was “really, really precise in framing an argument.”

Crane said the school had a “wonderful balance of support, along with constructive criticism.”

Even today, “I have a little voice in my head, ‘What would they think? What would their reaction be?’”

Crane said it’s difficult to fully express his gratitude to those who helped.

“The only thing I can do is really try and pay it forward with my own students. I feel very grateful,” he said. “I take the mentoring and support really seriously in large part because of how grateful I am to the people at UVA. I feel like I should send them an email every week that says thank you and nothing else.”

4. A People Place

Crane said he felt the same support from fellow alumni as he went on the job market. When he ran into UVA Law graduates at other institutions, he said, “there was an immediate kinship — we’re part of this special club that’s going to look out for each other.” Kendrick said the Law School is a place that attracts students with “good people skills.” “The law students here are good with people — they’re good friends, they’re good mentors to each other, they’re good leaders,” she said.

The school’s community spirit and the good feelings it generates — UVA was No. 1 in quality of life in the Princeton Review’s 2016 rankings — can have a lasting impact on those not only considering teaching, but pursuing administrative careers in higher education. “Serving in administrative roles such as the dean of students or academic affairs, as about 140 of our graduates do, for example, requires exactly the people skills UVA fosters,” Goluboff said.

The University of South Dakota’s Tiffany Graham, an associate dean of academic affairs whose duties are like those of a vice dean, took a different path to legal academia. After working at Quinn Emmanuel in Los Angeles as an associate for two years, she began thinking about what made her happy during her law school days: interacting with students as a Peer Advisor.

Courses with Barry Cushman (now at Notre Dame), Blasi, Harrison and Bill Stuntz ’84, who died in 2011 while a professor at Harvard Law School, allowed her to explore what was “intellectually interesting.” Those classes “helped me figure out what I wanted to teach and what I wanted to write about,” she said, which turned out to be constitutional law and sexuality and the law.

Yet teaching wasn’t on her agenda in law school.

“I was just focused on doing what others did,” she said — going to a firm. She clerked on the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia before joining Quinn, then later started her academic career at Villanova University School of Law. Though she has no ties to South Dakota (she’s from Cleveland), she said serving as the associate dean offered the perfect combination of teaching and working with students and faculty.

Graham’s administrative role puts her in charge of implementing the entire academic program at the law school, developing academic policies and programming, helping students with advising issues, ensuring compliance with accreditation standards, and working closely with faculty in developing their own scholarly agenda, among other duties.

“I love school, and I really love being in a position where I can continually educate myself and others,” Graham said. “I have an incredible amount of respect for what my colleagues across the country do.”

5. A Training Ground for Citizen-Scholars

That same ethos of support has helped some of UVA’s star scholars acquire influential positions at other top law schools.

The list of scholars who spent their formative years at UVA tells the story: Pamela Karlan and George Triantis LL.M. ’98 (now at Stanford), Saul Levmore (Chicago), former Dean Robert Scott and Tim Wu (Columbia), Klarman and Tomiko Brown-Nagin (Harvard), Jennifer Mnookin (dean at UCLA Law), Daryl Levinson and Chris Sprigman (NYU), and Stuntz, generally regarded as the foremost criminal procedure scholar of his generation.

“It’s success for us when other schools recruit our faculty,” Goluboff said. “People who learned how to do scholarship here now do it at an elite level all around the country. They are not only evidence of how we grow outstanding scholars — they are also ambassadors for the Virginia way.”

Klarman, who taught at Virginia from 1987 to 2008 before leaving for Harvard and his beloved Red Sox, said he considered himself “fortunate” to have started his teaching career at UVA.

“The Virginia faculty modeled what I now understand to be good behavior in a number of ways,” Klarman said. “First, it was very clear from the beginning that good teaching was expected from the faculty. Not every law faculty values good teaching, but Virginia clearly does. There have been legendary teachers, many of whom employ very different teaching methodologies, from the day I started until the present day: Bob Scott, John Jeffries, Saul Levmore, Paul Mahoney, Pam Karlan, Bill Stuntz, Caleb Nelson, John Harrison, Jim Ryan, Risa Goluboff — etc. Relatedly, it was also very clear, from observing the most important and valued members of the faculty, that there was not perceived to be any tradeoff between good scholarship, good teaching and good institutional citizenship.”

Virginia’s faculty regard teaching and scholarship as a “collective enterprise,” he said.

“People read each other’s scholarship and make it better,” Klarman said. “People devote years of their busy careers to serving as associate deans and appointments committee chairs. These are contributions to the public good that are invaluable, that aren’t necessarily people’s favorite ways to spend their time, that don’t necessarily contribute to their own scholarly reputations, but without which a healthy, thriving institution is impossible.”

Klarman said he started teaching the year after Stuntz began, and the same year as former professor Elizabeth Scott ’77, now at Columbia.

“We talked about what we were doing in class and how to approach it, literally every day,” he said.

He watched teachers like Jeffries for methods to improve his own teaching, and benefited from having his scholarship read and commented on by a long list of faculty.

“I learned from my 21 years at Virginia that teaching is the most important thing we do as law professors, that there is no tension between being a good teacher and a good scholar,” Klarman said. “A healthy law school is a collectivity that is more than its individual parts. An important part of the job is trying to make one’s colleagues and one’s institution better.”

5 LEADERS

- The Champion: University of California President Janet Napolitano ’83 Rises to Support Undocumented Students

- The Transformer: Taylor Reveley III ’68 Helped Transform William & Mary’s Law School, Then the Entire College

- The Motivator: Stanford Law School Dean M. Elizabeth Magill ’95 Has Made Her Mark by Getting Things Done

- The Diplomat: Through Deanships at George Washington and Wake Forest Law Schools, Blake Morant ’78 Offers Wisdom

- The Inspirer: Harvard’s Jim Ryan ’92 Connects With Students and Alumni Through Words and Actions

5 SCHOLARS

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.

UVA Law in Higher Ed: By the Numbers

UVA Law in Higher Ed: By the Numbers