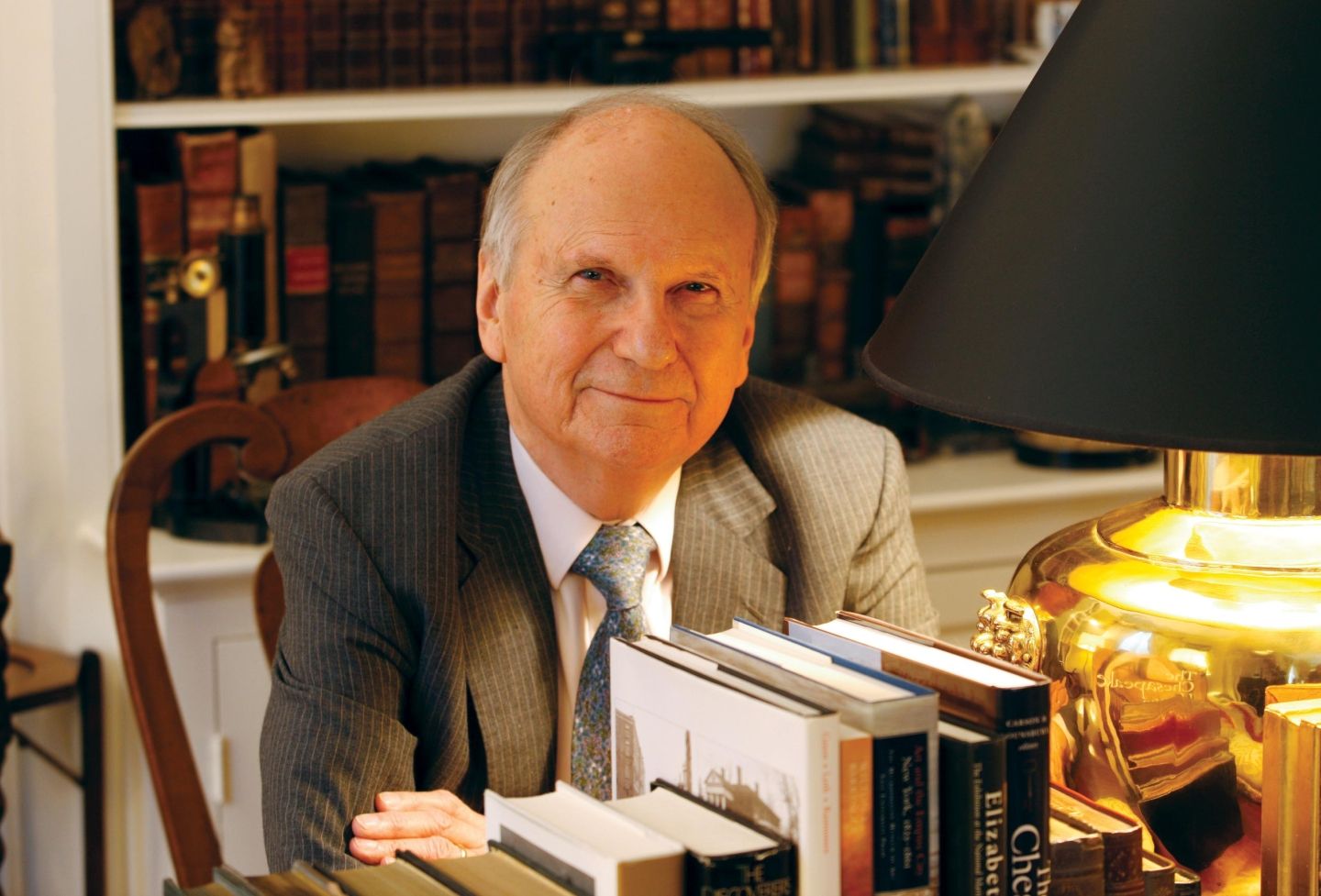

A breakthrough new empirical initiative developed by University of Virginia School of Law professor Kevin Cope could provide the most accurate estimate to date of federal judges’ ideologies, using automated analysis of text to evaluate lawyers’ written observations.

Cope started the project, called the Jurist-Derived Judicial Ideology Scores — or JuDJIS, pronounced “judges” — in 2016, but it arrives in another presidential election year, a time when court watchers speculate about potential judicial nominees and how their ideology might shape the direction of society. JuDJIS will offer researchers, journalists and policymakers the first systematic scoring of judges’ ideologies based on direct observations, while previous initiatives have relied on proxies and affiliations to calculate an ideological score.

The results have already yielded some surprises.

When Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement in 2018, Cope used preliminary data from an earlier stage of the JuDJIS project to estimate the ideologies of 10 judges mentioned as possible replacements. The study, published online in The Washington Post, showed that — based on their appellate records — both Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch might be more moderate as justices than many had thought. That prediction has largely been borne out, Cope said.

“The existing ideology measures have been cited in thousands of studies — they’re a cornerstone of the field of courts and judicial behavior — but, like any measure, they each have strengths and limitations,” Cope said. “I hope it will be a breakthrough for the sort of research that can be done in this field, in part because it will rate every Article III judge [those who have life tenure] on a single scale.”

In addition to evaluating judges individually, the JuDJIS data can show the ideological bent of different courts and track ideology of specific courts, or the entire judiciary, over time.

“The data actually show the judiciary has become less polarized over the last few decades, which is contrary to what some might expect and certainly the opposite of what has happened with Congress,” Cope said.

According to Cope, the two most frequently used judicial ideology measures for appellate judges are the Judicial Common Space and the Database on Ideology, Money in Politics, and Elections (DIME)/Clerkship-Based Ideology scores. Both rely on external proxies to assign an ideology rating, with Judicial Common Space ascribing to the nominee the ideology of the nominee’s same-party home-state senator (who must support a nomination for it to go forward), and the Clerkship-Based Ideology system assigning a score based on the campaign contributions of the clerks the judge has hired.

Measuring appellate or trial judges’ ideologies against each other is difficult, Cope said, because each judge hears a different set of cases.

“The existing lower-court scoring methods represent really creative and innovative approaches to solving this problem,” he said.

Yet those developers are among the first to acknowledge that both models are somewhat “attenuated” ways of getting at a judge’s ideology, in that they’re a few steps removed from the judge’s actual views and actions, Cope said.

In addition, a judge’s Judicial Common Space score is “locked in” by their home-state senator’s ideology before they join the bench. And while a Clerkship-Based Ideology score can change over time, most judges aren’t included because not all clerks donate, he said.

Adam Chilton, a professor at the University of Chicago Law School who is part of the team behind the 2017 Clerkship-Based Ideology initiative, agreed that JuDJIS is taking a different tack.

“Until now, there hasn’t been a measure of judicial ideology that is based on judges’ actual performance in their job, dynamically changes over time and has complete coverage across the federal judiciary,” Chilton said. “JuDJIS has all those qualities and, as a result, has the potential to become the new gold standard in measuring judicial ideology.”

Despite the cutting-edge methods used to make JuDJIS, Cope built the alternative analytical model on an old-school underlying technology: loose-leaf paper inserts to the Wolters Kluwer “Almanac of the Federal Judiciary,” a subscription service that includes “candid, revealing commentary” by lawyers based on their experiences before federal judges, according to their website.

“For most of the almanac’s history, three times a year, library staff around the country took out and discarded the old pages,” Cope said.

And no electronic backup was retained.

“So I thought, if I could somehow get ahold of all of those hundreds of back issues and digitize them, I could create a new data set going back to the ’80s.”

In 2017, Wolters Kluwer officials gave Cope hundreds of thousands of pages dating back to 1985 — the world’s only remaining copy. In 2023, the PDFs were then digitized and organized using a text-analysis program developed with the help of Li Zhang, head of the UVA Legal Data Lab.

Zhang, a computational social scientist, applied his expertise in data cleaning, modeling and natural language processing to identify discrete chunks of pertinent language in the lawyers’ evaluations.

Using a “hierarchical n-gram approach,” Cope and Zhang created a dictionary of the 8,000 or so most-used phrases in the entire body of evaluations. Human coders then assigned an ideological score to each of the phrases in the dictionary on a seven-point scale.

“A phrase like ‘slightest defense-leaning’ has a different meaning than ‘defense-leaning,’” Cope said. “In the same evaluation, ‘slightest defense-leaning’ moderates ‘defense-leaning,’ so you need to train the algorithm that the tri-gram here trumps the bi-gram so it doesn’t double count the phrases.”

The evaluations are then scored accordingly, and the judge is assigned an ideological score based on their average score in all evaluations. By systematically applying that methodology to every Article III judge, JuDJIS achieves a 70% correlation between ideological scores and the case outcomes that such a score would predict.

Zhang said the process was “long and iterative” because they needed to account for the potential changes, errors and inconsistencies over the underlying almanac’s four decades. He also said he sees JuDJIS as complementing its predecessors.

“We made efforts to ensure that the research community and the public can make use of the JuDJIS data in conjunction with existing models at different levels of granularity,” Zhang said.

“Li has been invaluable over the past 10 months in helping to develop the underlying text analysis method and applying it to this [data set],” Cope said. “Having him as part of the Law School’s research team is already expanding possibilities for the types of cutting-edge empirical legal research the faculty here can do — this project is one example.”

The two have a separate working paper, “A Hierarchical Dictionary Method for Analyzing Legal and Political Texts Via Nested n-Grams,” to explain how the methodology could be used for a host of other applications in law and political research, such as corporate statements and human rights country reports.

“Figuring out how machines can derive accurate meaning from language has long proven a huge challenge for data and social scientists,” Cope said. “Humans are really good at finding meaning in legal writing, but every time a person does it — even the same person — they may find a slightly different meaning. Computational methods of text analysis can address this problem, if it’s done right.”

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.