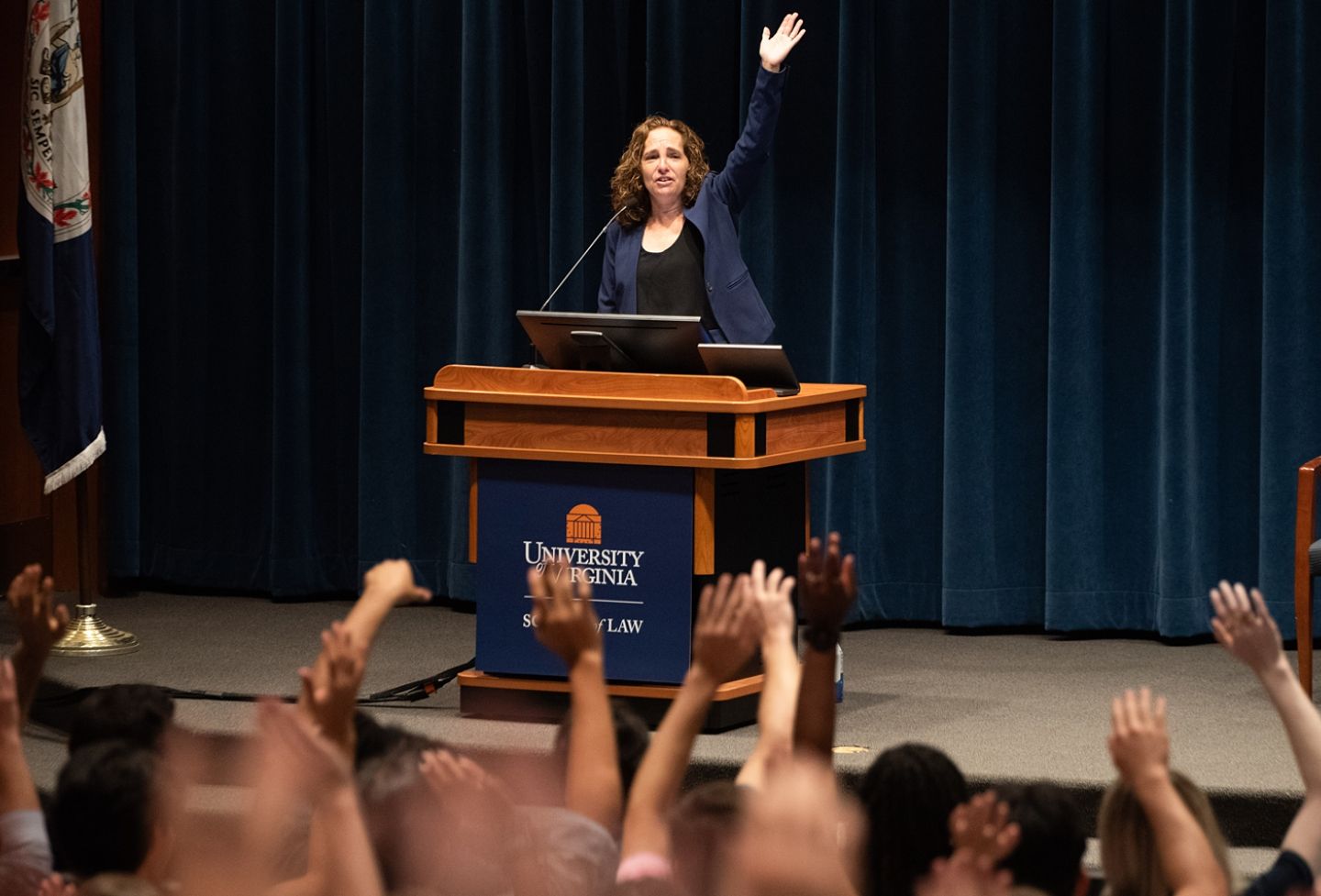

Dean Risa Goluboff welcomes new students in the Class of 2026 to UVA Law School.

Transcript

RISA GOLUBOFF: Thank you, Natalie. Those were wonderful words. And you'll see there are going to be some themes that repeat. Not all, but there are going to be some themes that repeat because there are real continuities here about who we are, and who you all are, and what we're doing here.

All right, so it's my turn now to share some thoughts with you on this really momentous day of your lives. I've already had an opportunity, as I said, to speak to the SJD, LLM, and exchange students. So some of my remarks are more geared toward our new JD students, but that said, I hope that they will resonate for everyone in the audience.

So today is the beginning of the rest of your lives. Clearly, that's true. But I mean that in one specific way. Until now, you have been lay people -- lay people in the world -- just normal, everyday people. But today, you are beginning your professional journey. You are starting your journey into the learned profession of the law. And you are going to become lawyers.

And that is really transformational. And it's really momentous. I think often about the white coat ceremony that they have in medical school. And I think, what can we do? Do we give you a gavel? I can't think of a -- and what do we do here? I'll come back to this in a little bit. We talk, as Natalie said. That's what we do professionally, we talk. So I don't have a gavel. And I don't have a white coat. But I'm going to talk at you, because that's what we do. So consider that your initiation.

So this is not just a momentous day for you individually in the choices that you've made, it's also a really momentous time to begin this adventure. There is a lot going on in the world. We have been navigating challenges for a number of years now. And we will continue to navigate them.

We're still navigating this global pandemic. There is war. There are economic ups and downs. We are living in a highly polarized political and cultural environment, both here and abroad. There is climate change and the many disasters we are seeing that are a result of climate change. There are major shifts in doctrine at the Supreme Court.

And I hope that when you think about all of those things, though they may provoke, and I'm sure do, provoke anxiety, you also feel like are in the right place to be thinking about them. And I know that many of you are here because of those global and national challenges. Others of you are here not thinking about those in particular.

But for whatever reason you are here, I am confident that this is the right moment to be in law school. Now, obviously, I run a law school, I think going to law school is always a good choice, no matter the moment. But I think it is the best and most important thing you can do right now, whatever your interests and relationships to these various developments. Because you will learn new ways of thinking, new ways of problem solving, new ways of analyzing these challenges and others. And it won't be easy, as Natalie said.

Law school is never easy. That's why they make movies about it and write books about it. You have seen people talk about the gauntlet. But it will also be, I hope, exhilarating, and energizing, and intellectually stimulating, and empowering, and very, very rewarding. And that is not just a hope, it's actually a prediction. I predict that it will be all those things, based on the 20-plus years I have spent studying lawyers, teaching lawyers, and leading an institution that educates lawyers.

So in law school, when you start your first assignments this weekend, you will read a lot of opinions by judges. And no offense to Judge Heytens, who I'm very excited to hear from, you will focus a lot on judges. And I want you to remember judges are not the only ones who make the law.

Behind every case are the lawyers. Now one day, some of you might be judges -- see e.g., Toby Heytens, who you'll hear from soon. But many, many more of you will be lawyers. And cases exist because real people experience real harms that they think the law can redress. And that they think lawyers can help them solve.

Lawyers wield enormous influence and power in response to those pleas. And I don't just mean the famous lawyers or the extraordinary lawyers, all lawyers wield this power. And this is the power to make law, to affect real institutions' lives, to affect institutions -- sorry -- real peoples' lives, institutions, companies, and nations.

The power of the law is to make, break, and enforce contracts. It is the power to put people in prison and get them out again. It is the power to wage war and end it. It is the power to create, or merge companies, or allow them to go bankrupt. And all this is to say that law is not some constant, external, foreign thing that exists out there in some vacuum. Law is made, not found. And it will eventually routinely and momentously be made by you, as you become advocates, and as you represent people and amplify the voices of others.

And it is my job and our job here at the law school to teach you that power, and to help you understand that power, and to make sure that you are equipped to deploy that power with integrity and responsibility. That is not easy. And it is not, as Natalie says, always comfortable. And the thing is, you have to do it.

I remember very vividly the moment in my law school career when I suddenly had the epiphany -- thinking like a lawyer, I have to make myself think like a lawyer. No one's going to do that for me. That's something I have to do myself and I'm going to talk about that more in a minute. And it is what we will be working on with you all the way through law school in pretty much everything you do here -- in your casual conversations in the halls with each, other in office hours, in your student orgs, and especially in your classes.

So I want to stop and talk for a minute about what those classes are going to be like. So there are three kinds of classes. There are -- I came up with this -- I'm very proud -- three P's -- principles, practice, and perspectives. So first are the first principles. That is what we mean when we say thinking like a lawyer -- how to analyze problems, how to break them down, how to reason with clarity, how to do analogical thinking. This is fundamental to what you are doing here in law school.

And so we start with this. And we immerse you in it. Your first semester is going to be all about learning how to think like a lawyer. And it might seem quite divorced from those momentous things going on in the world that I mentioned. And it might seem quite divorced from what brought you to law school in the first place, from your interests in the law, from hard moral or ethical questions. And it might be divorced at certain moments. But we start with these fundamentals because the faculty think it is necessary and important to becoming lawyers that you hone your analytical skills.

Now if this feels unnatural to you as you go through your first semester, and you wonder, is this really what I thought I was going to be doing in law school? There are lots of ways to explore those concerns and to remind yourself of why you're here. So you can ask your professors, why do you teach it this way? Why do you -- why do you want to hold in abeyance those big moral or ethical questions? Why are we so focused on the legal doctrine and the analytical moves?

Why do they make the choices they make? Why aren't they asking the questions you think are important? Because you need to understand why they think the questions they're asking are the important ones.

You should take opportunities to discuss your questions and your concerns with your colleagues, and your classmates, and especially with those who seem to take a different perspective. And even more especially, with our LLM, SJD, and exchange students, who come here from around the world, as well as from our own military, most of whom have practice experience, and all of whom can help you put what you're experiencing into a much larger perspective on what's going on in your legal education.

You should also be thinking, even as you're immersing yourself in these fundamentals, about what are the issues you want to explore in your future classes. You will have so many opportunities to delve into the things that you care about and to reengage with those issues and the passions that brought you to the law school after your first semester. So remember, you're going to have that opportunity.

And I think of the first semester of law school as a little bit like the moment when you have your first baby. You have no idea how long this part of the process is going to last. And it feels like forever. And you don't know anything. And you don't even what you don't.

And then suddenly, you're going to turn around, and it's going to be four months later, you're going to have taken your first exam. You'll be like, oh, it's OK now. But while you're in it, it is going to be very, very hard to see what's at the other side. But it will come, I promise you that.

And finally, I encourage you from the very beginning of law school, find ways to continue to stoke your passions. Find ways to continue to engage with the things that you care about outside the classroom. Join student organizations, do pro bono work. Get engaged in the Charlottesville community. Get outside the law school. There are so many opportunities.

And don't forget who it is you are when you came here, and what it is want to do. That's not necessarily going to happen in the classroom in this first semester, but that doesn't mean it shouldn't be happening. And you should find ways to continue to feed those interests.

So learning how to think like a lawyer, as I said, I remember -- and it wasn't with joy that I remember this epiphany -- of thinking, oh, my god, I have to do this to myself. It's going to be hard, but it will be utterly transformative. OK, so thinking like a lawyer, that's the P, the principles, the first of the three types of learning you will do.

The second two, you'll do a little bit in this first semester, but you'll do it more and more over the course of your three years. The second is practice. This is experiential learning that teaches you skills and the actual work of being a lawyer. It is also the places where you will really hone your integrity and your judgment. These are in our clinics, our externships, our pro bono work, negotiations courses, summer jobs, alternative spring break, work over winter break. And these practical courses will offer you real insight into your own interests and into the practice areas you're interested.

There's often a huge difference between the subject matter of a course and what it's like to practice in that subject matter, and the pace, and the dynamics. Are you reading? Are you speaking? Is it one big case? Is a lot of little cases? Are you talking to clients? Are you not? There are lots of things like that that you don't yet. And you'll have many opportunities to try those on. And they will show you not only what it's like to practice, but also what it's like to be an advocate on behalf of others.

Some of you may already have done that. But for many of you, you may be thinking, I'm coming into law school to learn how to make arguments, and you are. But most of the time as a lawyer, you're making those arguments not for yourself, but for someone else. And the earlier you start engaging in that practice of representation, the more, one, you're going to feel like a real lawyer, and the more, two, you're going to hone the integrity and judgment that will make you, as Natalie said, a great lawyer.

The third type of course are perspectives courses, courses in a wide array of scholarly perspectives that foster the big-picture thinking that is critical to both lawyering and to leadership. Our faculty are experts in history, jurisprudence, economics, psychology, politics, philosophy, religion, and sociology, as well as law. And taking classes in these cognate areas will enable you to ask and answer the big questions about justice, about the rule of law, and about the operation of the law at a very high level.

Each of you will take a different mix of these courses over your time here, but all three are critical. And they will enable you to learn not only how to manipulate set legal categories, which is your job for this first semester, but also to take ownership over the law, over what it is fundamentally and what it should be.

Now becoming the lawyers you are here to become is not only about the classes that you will take. It's also about how you approach them and what you take away from them. It's about doing this to yourself. And that means seeing your education as a partnership attended to achieve mastery. This will likely require a different way of studying. And it may take you some time to figure it out.

But you are not here to consume information. You are not here just to get knowledge. Obviously, you're going to get knowledge. But that is not the primary goal of your studying. You are learning a new way to think. And I would add to the keep your eyes on the screen, that Natalie mentioned, I would add talk to each other. Talk it through. When you come to a moment where you're not sure and you can either push through, which you should do, or stop, you have a third option -- talk to somebody else.

Talk to somebody who you think seems pretty smart. Talk to somebody who you think might disagree with you. Talk to somebody who you think might understand or might not, and you can figure it out together. But doing that, having those conversations -- and I will tell you, even if I didn't tell you to do it, you would do it anyway -- but I encourage you it's not a sign of weakness. It's a sign of strength. And it's a way to move forward and to continue moving forward.

And I will light up every time I walk through the halls after a class and I hear students talking to each other about what they just learned. And it happens all the time. But what I'm saying to you is, do it self-consciously. Do it in moments of need. Do it when you don't understand, as well as when you're engaged, and you just heard the professor say something crazy, and you guys all want to talk about it. That's all good. But do it also with intent.

Because you need to be active participants in this process. And that means you need to reach out. And it means you have to be brave. And it means you have to take risks. You have to own your own adventure.

So everybody, raise your hands. Raise your hand -- raise your hand. Everybody, raise your hand. OK, now everybody say UVA Law.

AUDIENCE: UVA Law.

RISA GOLUBOFF: OK, you can put your hands down. You've now done the two hardest things in law school. Raising your hand for the first time and speaking in class for the first time.

[LAUGHTER]

And this class is way bigger than any other class you're going to have. OK, so when you think to yourself, am I going to volunteer? When you think to yourself, am I going to raise my hand? When you think to myself, am I going to say this thing that I have in my head to say? Don't think this would be the first time -- oh, that's scary. No, I already did that. I already did that in front of 350 people. I already did it. And so I can do it now.

And I urge you, start doing it from the beginning. Start doing it immediately upon coming in to law school. Participation can be uncomfortable in all those ways that Natalie said. But participation is a gift. It's a gift to you that you are participating in your education. And it is a gift to everyone around you, who is going to learn from you, as well as from the professors.

We are an educational process all about dialogue, all about the exchange of ideas. And you need to engage in that. So participation leads to mastery, leads to ownership, and leads to you being the people who are going to truly make the law.

So Natalie and I have said this a number of times. And we're going to keep saying this. Because it's true. Law school is not going to be easy. And that process is not going to be easy. And it's going to be a little scary. But I learned a phrase yesterday from our community fellows -- struggling gracefully. I encourage you to struggle gracefully.

When things are hard, you struggle through them, and you give grace to those around you who are also struggling through them. And you give grace to yourself as you do so. So I hope -- that phrase just really captured something for me, and I hope that you will find it helpful as well.

I do want to add one thing as well about the not easy, and about you here, and your belonging here. We know you can do all the things we are asking of you. We are asking -- law school is asking a lot of you. And we have every confidence that you are capable of doing it.

We are no longer in the world from the Paper Chase -- look to your left, look to your right, one of you won't be here. That is not our world. We have every expectation that every one of you is going to graduate, pass the bar, and have a wonderful, successful, incredible career.

And beyond having that expectation, the American Bar Association, our accreditor, the rules from the American Bar Association are you shouldn't accept anyone to your law school who is not going to succeed. So we would not be in compliance if we accepted anyone who we didn't think was going to succeed. So I hope that will put to rest all the fears that you have. I know it won't put them to rest, and you will feel them other times. But just remember, Dean Goluboff would not violate ABA rules.

So if I am here, I am here for a reason. So we don't say it's hard to suggest that you can't do it. We know you can do it. We say it's hard to say, when you experience it hard, don't think that means I don't belong here. Think that's what's supposed to be happening. That's exactly what should be happening here.

Now when you achieve the mastery that you are here to achieve, to become the lawyers you are here to become, two things come with that. The first is opportunity. You can do literally anything from this law school. So you should dream big, and you should make those dreams happen. Careers are long. They are not linear. And every single one is different.

Law school is your chance to prepare yourself for the whole long, wide-ranging, unique career that will be yours. And it will be amazing and wondrous. And I know that even if you are not sure of that. Because I know those who have come before you, those who have clerked for judges, and practiced in nonprofits, or in government, or in firms.

I know the CEOs of hedge funds, and the heads of legal aids, and the US attorneys, and the TJAG, and congresspeople, and presidents, and judges, and Toby Heytens, who you'll hear from in a moment, and even the New York Times puzzle master, who is a UVA Law grad. I said, you can do anything.

Now, don't worry if I announce all those things, and you're, like, oh, I don't what it is I want to do yet. You shouldn't know. You just got here. It's OK. You have so much to learn. And there are so many possibilities that you will have the opportunity to dream about.

Now, the cognate to opportunity that comes with mastery and power is responsibility. Law is not just a job. It is a learned profession. It is marked by extensive learning -- or erudition -- that is the idea of a learned profession. And it is professed -- the profession part of the learned profession -- to the core values of justice and the rule of law.

Becoming a lawyer means that you are entrusted with the knowledge and license to practice law. It means that you will have obligations to do public good, as well as work for private gain and personal glory. And holding that public trust begins now in law school with pro bono projects, with externships, with summer jobs. I could not encourage you in more emphatic terms to take one of our 24 amazing clinics, where you will get real-world experience and skills. And you will work with real people and clients and discharge your obligation to serve the public.

So you should start thinking of yourselves not only as lawyers, but also as public servants. And there are many ways to fulfill that responsibility, not only through full-time public service work, which many of you will pursue, but also through pro bono work, through board work, through community organizations. There are myriad choices of how to pursue it, in what realm, on whose behalf, and to wield that power responsibly. You can choose how.

But you should know that all paths flow through your understanding of yourselves as active participants in the law, and thus, in the governance and leadership of American society and the larger global community. There is no better place to become such a lawyer than here. And that is true for all the obvious reasons that made you choose this place -- our fabulous faculty, our impressive students, our amazing administrators and staff, our vast curriculum. You know all that. That's why you chose this place.

But you also more than that, the kinds of things that Natalie was talking about, she thinks about in admissions. You know that our faculty, our staff, our students, our alumni are all engaged in a shared enterprise beyond the formal curriculum and beyond the professionalization process, a shared enterprise of being a real community that simultaneously supports and challenges its members.

We, you, all of us come from different backgrounds, experiences. We hold different views and attitudes. We have different politics and interests. We have different hopes and dreams. And we come from all over the world. And across all those differences, we have chosen this place, not only because of its excellence, but because of its community across those differences. We share fundamental values about our interactions with each other, values of joy, humanity, respect, dialogue, collaboration, and a community across those differences.

And this combination of diversity of experience, background, perspective, and viewpoint, with a commitment to community, that combination is very rare. We are a big tent here. And that is one of our greatest strengths as an institution. And we are a big tent who are not siloed, but engaged, because we share a single community. And that is not only what makes your experience so wonderful here, and what makes UVA Law graduates love this institution so much even after they leave, it's also a key ingredient to your success.

Learning to talk to people who are different from you, learning to collaborate with them, understanding where disagreements are fundamental, and where they are not, and working through them. As members of a community, we can reach across our differences to engage in ongoing, respectful, empathetic, and robust exchange of ideas because we know each other as real people, because we see each other in lots of different situations. Because we are not simply one view that we may hold.

Doing so is essential not only to our values as an institution, and not only to our educational mission, but to becoming the great lawyers you are here to become. The legal profession's commitment to the rule of law, its profession to the rule of law, is a commitment to the idea of resolving conflict through dialogue and persuasion, not through force, or coercion, or fiat.

It is why one collective noun for lawyers -- collective noun -- think a pride of lions -- a collective noun for lawyers is an eloquence of lawyers. There are other collective nouns for lawyers. I'm not going to share them all with you. They are not as flattering. But an eloquence of lawyers is a beautiful phrase. And it captures so much.

And becoming an eloquent lawyer begins in law school, where your ideas and opinions will be stretched, challenged, and tested by your professors, by your peers, by visiting speakers. Inside the classroom, outside the classroom, you will encounter thoughts positions and views that run counter to your own, that you might even abhor. And the lawyer's commitment to hearing and analyzing every argument, to understanding how to problem solve, it requires hearing even those things that are hard to hear, which they sometimes will be, and even when the opposing positions are things with which you deeply disagree.

But these are the moments, as Natalie said, that will enable you to test your own beliefs, and critically, to make the best arguments on behalf of your clients. This isn't easy, and we don't take any of it for granted. We are always looking for ways to foster the kind of community and belonging in which the free exchange of ideas can truly occur. But we -- the law school, the administrators who are just walking in, who you'll meet in a few minutes -- we can't do that for you.

We can articulate the value of a diverse and inclusive community and create the conditions for it. We can articulate the value of the free exchange of ideas and create the conditions for it. But it is up to each one of you and each member of this law school community to sustain that community and to engage in that exchange. So treat one another with empathy, respect, and a generosity of spirit. And test every idea, both alone and together, as you struggle gracefully and give grace both to yourselves and to others.

Talk in class. Listen to your professors and your peers. Go to office hours. And a favorite of our president, and former law graduate and faculty member, Jim Ryan, ask questions of those with whom you disagree and consider their answers. I know that you are up to the challenge, even in a year, when we will no doubt disagree about politics, elections, cases, and the major issues facing the world that I mentioned at the beginning of this speech.

Meeting that challenge is a major part of what will actually make your time here transformative and make you into UVA lawyers-- lawyers who not only the law, but shape it, who think not only about what can be done, but what should be done, who not only practice the law, but lead it, and who know how to disagree, and resolve conflict, and collaborate. It is what will make you the best hope for the future of our profession and our nation. That all begins now. You all are ready. And I cannot wait to see what you will do. Thank you.

[APPLAUSE]