Firm’s Fellowship Honors Caplin ’40, Swanson ’51

A law firm’s new fellowship honoring two University of Virginia School of Law alumni was announced Feb. 19.

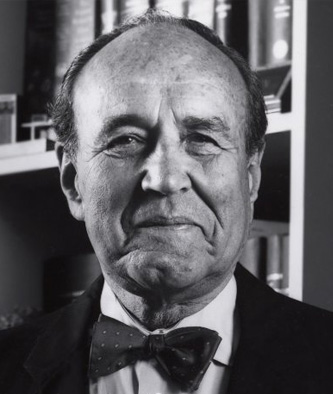

The Caplin-Swanson Diversity Fellowship, created by Caplin & Drysdale and given to law students who intern over the summer at the firm, honors Mortimer M. Caplin ’40 (left), a UVA Law professor who served as IRS commissioner in the Kennedy administration, and Gregory H. Swanson ’51 (below right), UVA and the Law School’s first Black student. Caplin founded Caplin & Drysdale with Law School lecturer Douglas D. Drysdale ’53 in 1964.

The Caplin-Swanson Diversity Fellowship, created by Caplin & Drysdale and given to law students who intern over the summer at the firm, honors Mortimer M. Caplin ’40 (left), a UVA Law professor who served as IRS commissioner in the Kennedy administration, and Gregory H. Swanson ’51 (below right), UVA and the Law School’s first Black student. Caplin founded Caplin & Drysdale with Law School lecturer Douglas D. Drysdale ’53 in 1964.

“I know my father would be smiling from ear to ear to celebrate the values celebrated in this very important initiative,” Michael Caplin ’76 said at the virtual event announcing the fellowship.

With Caplin’s support, the Law School initially accepted Swanson’s application, but the Board of Visitors rejected it in July 1950, citing state laws affirming segregation. With the help of a legal team including Thurgood Marshall, Oliver Hill, Martin A. Martin and Spottswood Robinson of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a three-judge panel ruled in Swanson’s favor that September, and he registered in time for fall classes. Swanson completed a year of studies at the school, though never completed the thesis required to receive an LL.M. degree, which was common for master’s students at the time. Swanson already held a law degree from Howard University.

Professor Kim Forde-Mazrui, director of the Center for the Study of Race and Law, served as guest speaker at the fellowship’s announcement. He shared details uncovered from research conducted by the late UVA Law professor J. Gordon Hylton ’77, as well as stories provided by the Swanson family.

Professor Kim Forde-Mazrui, director of the Center for the Study of Race and Law, served as guest speaker at the fellowship’s announcement. He shared details uncovered from research conducted by the late UVA Law professor J. Gordon Hylton ’77, as well as stories provided by the Swanson family.

Robert F. Kennedy ’51 befriended Swanson at the Law School, Forde-Mazrui noted.

“Bobby Kennedy and Swanson ran into each other in D.C. in probably 1961, and Bobby said, ‘Hey, my older brother just appointed Professor Caplin to be the IRS commissioner, and he’s looking for good tax lawyers,’” Forde-Mazrui recalled. “And that reconnected Swanson with both Bobby Kennedy and Mortimer Caplin, and that’s how Swanson wound up working at the IRS for the rest of his career.”

At the event, Caplin & Drysdale announced the first fellowship recipient: Brooke Radford, a second-year student at Howard University School of Law.

“This is a wonderful day, and I look forward to continuing the legacies [of Mortimer Caplin and Gregory Swanson] as we … work towards racial justice in our future,” Dean Risa Goluboff said at the event.

—Mike Fox

1953

In Memoriam: Alan S. Boyd ’48, First U.S. Secretary of Transportation

Alan S. Boyd ’48, the first U.S. secretary of transportation, died Oct. 18. He was 98.

Alan S. Boyd ’48, the first U.S. secretary of transportation, died Oct. 18. He was 98.

Sworn in as secretary with President Lyndon B. Johnson at his side in January 1967, Boyd pulled together a patchwork of smaller federal transportation agencies to create the Department of Transportation. The nation’s urban transportation systems, for example, had been under the control of Housing and Urban Development.

Boyd, who previously served as undersecretary of commerce for transportation, was influential in promoting vehicle safety standards, including the requirement of seatbelts for all new cars, among other accomplishments.

The Washington Post put his role in perspective. Boyd “coordinated the country’s overarching transportation policy, giving equal weight to plane, train and automobile travel. His efforts laid the foundation for a Cabinet-level agency that has grown from a $5.5 billion to $76.5 billion budget, with a role in highway safety as well as the Saint Lawrence Seaway.”

The New York Times observed, “Despite resistance from bureaucrats and maritime unions, and having to work with underfunded mass transit systems, Mr. Boyd won relatively high marks for a two-year effort to merge dozens of transportation-related federal agencies.”

Boyd solidified his path to transportation secretary as a Johnson appointee in 1965, serving as commerce undersecretary and as part of a special committee that recommended creating the department. He used his political experience in Washington to help shuttle the bill through Congress. Boyd had previously served as a member and chair of the U.S. Civil Aeronautics Board, first appointed by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1959.

In his 2016 autobiography, “A Great Honor: My Life Shaping 20th Century Transportation,” Boyd detailed his call to Johnson after a friend who was a White House assistant erroneously told him he wasn’t going to be picked for secretary.

“I called the president and told him that he didn’t owe me anything and that I had been honored to serve him in the capacities to which he had appointed me,” Boyd writes. “I added that if I could be of any service to him in the future, I would be happy to do so, but that I would also be happy to leave the government satisfied that I had done the best job I knew how.”

Johnson responded, “What the hell are you talking about?” The president later added, “Alan, don’t you do any damn fool thing. Just sit tight and shut up!”

It was all a misunderstanding; Boyd was in.

In the years following his public service in the Johnson administration, Boyd served as president of the Illinois Central Railroad (1970-77), as president of the quasi-public Amtrak passenger rail service (1978-82), and as chairman and president of the North American subsidiary of Airbus Industrie, the French jetliner company (1982-92).

He briefly worked for another U.S. president, Jimmy Carter, in 1977 as Carter’s special representative negotiating a new U.S.-U.K. bilateral aviation agreement.

He began his career in private legal practice in Miami. But a law firm partner engaged in politics and a subsequent job with the Florida State Turnpike Authority set him on his way for a career in government focused on transportation. He served on the Florida Railroad and Public Utilities Commission before heading to Washington.

In his autobiography, Boyd credited Law School Dean F.D.G. Ribble 1921 for giving him a chance to study law following his service in World War II as an Army pilot — despite flunking out of the University of Florida. If Boyd took undergraduate courses at UVA and performed well, the dean said he would reconsider the young man’s plea for admission.

“At the end of the semester, I brought my grades to Dean Ribble. I’d taken economics, public speaking, and history, and done very well in all three. He greeted me warmly and told me to plan on entering the law school the following Tuesday.”

Boyd’s two years of legal studies (condensed after the war from the standard three) included a self-guided course in aviation law. He noted that his application to work for the Civil Aeronautics Board immediately after passing the bar was rejected.

Boyd reinforces in the book how his time at UVA helped influence the principles by which he would live his life.

“I believe in honesty,” Boyd writes in the epilogue. “Like the University of Virginia, I have an honor code I follow. I know I could never live with myself if I ever lied or cheated. I want to look in the mirror every day and be proud of the person I see.”

His son, Mark T. Boyd, who notified the media of his father’s death, reiterated that thought in a letter last year to the Law School: “Dad credits his education at U.V.A. Law as foundational for his approach to life.”

—Eric Williamson

1955

Mark B. Sandground Sr. died Dec. 30. He was 88 and still practicing law with his own firm. According to family, he didn’t suffer much pain and was well cared for by the medical team at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he had been admitted two weeks prior.

Mark B. Sandground Sr. died Dec. 30. He was 88 and still practicing law with his own firm. According to family, he didn’t suffer much pain and was well cared for by the medical team at Sibley Memorial Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he had been admitted two weeks prior.1957

In Memoriam: John Paul Jones ’48, Newspaper Publisher and UVA Arena Namesake

John Paul “Jack” Jones ’48, a World War II veteran, successful attorney and newspaper publisher — and a lover of basketball, for whom UVA’s John Paul Jones Arena is named — died Nov. 20. He was 100.

John Paul “Jack” Jones ’48, a World War II veteran, successful attorney and newspaper publisher — and a lover of basketball, for whom UVA’s John Paul Jones Arena is named — died Nov. 20. He was 100.

“He was beloved by many and he loved the Hoos,” Virginia Director of Athletics Carla Williams said. “I’ll never forget the pure joy I saw in him for UVA and our men’s basketball program at the [2019] Final Four.”

After completing an undergraduate degree at Vanderbilt University in 1941, the San Antonio native joined the U.S. Navy and served in World War II. In 1946, Jones entered the Law School and earned a J.D. in 1948, subsequently starting a law practice in Memphis that specialized in interstate commerce and labor law.

But Jones also had newspaper ink in his blood. Jones’ grandfather, Charles L. Berlin, had helped start what became the Memphis Daily News — originally known as the Daily Abstract of Transfers — in 1886. Jones’ mother took over as publisher in 1909, before handing the reins to Jones in 1960. He worked at the newspaper until 1994.

Jones considered himself a “history junkie.” He had a strong interest in American history, especially the friendship between two of America’s founding fathers, Thomas Jefferson and naval officer John Paul Jones (no relation), which he learned of when he was a law student in Charlottesville.

In his retirement, Jones focused on philanthropic activities. Among many endeavors, he served on the board of the Memphis Literacy Council, the American Cancer Society and Future Memphis.

In 1996, Jones’ sons, Paul Tudor Jones II (College ’76) and Peter Schutt, endowed a scholarship in his honor at the University of Memphis School of Journalism. Paul Tudor Jones later donated $35 million in his father’s name as the lead gift for UVA’s John Paul Jones Arena.

In a 2016 interview with The Daily Progress, Paul Tudor Jones said his father became a basketball “fanatic” after his mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

“There’s no doubt in my mind that he’s alive today because of Virginia basketball and Memphis Grizzlies [NBA] basketball,” Tudor Jones said. “It literally is what keeps him going.”

John Paul Jones Arena opened on Nov. 12, 2006, with John Paul Jones accepting the ceremonial game ball prior to the Cavalier men’s basketball team’s 93-90 win over Arizona.

“Jack had an extraordinary love for the University — and UVA basketball,” said Barry Parkhill, Virginia’s associate athletic director for development. “He always had that special twinkle in his eyes. He was a great American.”

—Whitelaw Reid

1958

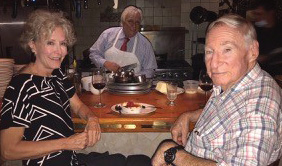

Ben Phipps had and is having a jubilant time, first confined, but socially distanced, with Mrs. J.J. Wilson (pictured), a striking, lovely younger lawyer. He sent another picture, smiling midst his camellias in Tallahassee, Fla., where vaccine priorities go first not to health workers but to lawyers. So, he got an early shot and recently rattled off names of political figures he deals with by the dozens in Vero Beach to impress retired secretary Ted Torrance.

Ben Phipps had and is having a jubilant time, first confined, but socially distanced, with Mrs. J.J. Wilson (pictured), a striking, lovely younger lawyer. He sent another picture, smiling midst his camellias in Tallahassee, Fla., where vaccine priorities go first not to health workers but to lawyers. So, he got an early shot and recently rattled off names of political figures he deals with by the dozens in Vero Beach to impress retired secretary Ted Torrance.1959

1960

1962

In Memoriam: Albert R. Turnbull ’62 Launched Careers of Generations of Lawyers

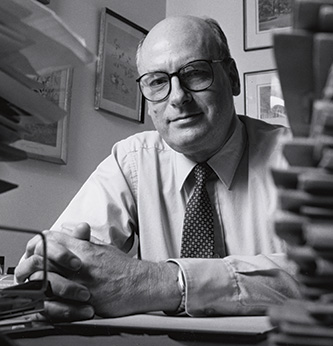

Former Associate Dean for Admissions and Placement Albert R. Turnbull ’62, who admitted and helped shape generations of lawyers at the Law School, died Jan. 25. He was 83.

Former Associate Dean for Admissions and Placement Albert R. Turnbull ’62, who admitted and helped shape generations of lawyers at the Law School, died Jan. 25. He was 83.

When he retired in 2002 as professor emeritus, Turnbull was estimated to have admitted 80% of living alumni of the school — more than 13,000 students. During his 36-year career at UVA leading admissions and career placement efforts, as well as teaching professional ethics and responsibility courses, he also influenced law school admissions nationally through his various roles at the Law School Admission Council. In 1972, Turnbull worked on the three-person subcommittee that created the Law School Data Assembly Service, a tool that admissions offices at every American law school use to evaluate an applicant’s transcript, GPA, LSAT scores and other factors. Later, he was a member of LSAC’s Board of Trustees when the organization decided to break from Educational Testing Services and administer the LSAT alone.

“For thousands of applicants, Al Turnbull was the face of the Law School,” said Professor John C. Jeffries Jr. ’73, who was dean when Turnbull retired. “He was always humane and caring. He treated each and every applicant as an individual deserving of respect, and they repaid him with admiration and gratitude.”

A native of Virginia Beach, Va., and a graduate of Princeton University, Turnbull was a standout student at the Law School. He won the William Minor Lile Moot Court competition with his classmate and close friend, Charles Kidd ’62. After graduation, he clerked for Judge T.J. Michie 1921 of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia, and then served as a trial and appellate attorney for two years in Norfolk, Virginia. (That work eventually led Turnbull to argue Warden v. Hayden at the U.S. Supreme Court in 1967. The case established a “hot pursuit” exception for broad searches under the Fourth Amendment.)

Dean Hardy Cross Dillard ’27 then called him back to the Law School to both teach and lead the admissions and placement effort.

Initially assisted only by a cadre of faculty members, Turnbull oversaw a revolution in how admissions, career placement and financial aid worked. Turnbull’s own Class of 1962 only had 566 applicants. By 1966, his first year in admissions, the applicant pool expanded to 1,841, and kept growing. Employers took notice as well.

“We were getting more and more employers wanting to recruit here,” Turnbull said in a story marking his retirement. “The logistics of handling that were exploding.”

During the 1970s, the school created two assistant dean roles, for career services and financial aid, and continued to hire more staff over the years.

One of the candidates Turnbull often said he was proud to admit was Jim Ryan ’92, now president of UVA. Ryan had already been accepted to Yale and Harvard when Turnbull called to ask him to consider attending Virginia, with help from a full-tuition Hardy Cross Dillard Scholarship (now the Karsh-Dillard Scholarship), a program Turnbull spearheaded to help recruit elite prospects with financial support from Anthony Pilaro ’60, who also founded the Ron Brown Scholar Program. After Ryan visited Virginia, Turnbull sealed the deal.

“I owe much of my professional and personal life to Dean Turnbull, as attending UVA introduced me not just to the study and eventual teaching of the law, but also to lifelong friends and my wife, Katie, a UVA classmate,” said Ryan, who later served as professor and vice dean at the Law School. “Dean Turnbull was as kind as he was smart, and I will miss him dearly, as I know so many others will as well.”

Turnbull’s longtime friend and fishing partner Professor Alex Johnson said the dean was “ecstatic” to have played a role in recruiting Ryan and Provost Liz Magill ’95.

Johnson called Turnbull the “founding father of modern-day admissions.”

“People looked at him and the way he ran admissions as a model — a meticulous way to do it, to do it fairly, do it efficiently, do it with the right thoughts in mind and with the right ideals, including diversifying the legal profession. He had the utmost integrity and the utmost faith in LSAC and the admissions process.”

At their 40th reunion in 2002, on the eve of Turnbull’s retirement, the Class of 1962 honored Turnbull by renaming its class scholarship The Class of 1962 Albert R. Turnbull Scholarship.

Turnbull’s son, Albert W. Turnbull ’88, now associate general counsel and partner at Hogan Lovells, joined his father as a graduate of the school, as did Turnbull’s niece, Janet Turnbull ’04, a Justice Department attorney.

In addition to the scholarship, the Law School also named the Albert R. Turnbull Unrestricted Endowment in his honor.

—Mary Wood

1963

1964

1967

William Howell was elected to the board of directors of the Virginia War Memorial. Howell represented Virginia’s 28th District in the commonwealth’s House of Delegates for almost 30 years, from 1992 until 2018. He also served 15 years as speaker of the house — the second-longest serving speaker in state history. During his tenure, Howell played a critical role in the General Assembly’s strategic investment in education, economic development and mental health services. Of his many legislative achievements, one of his most notable was House Bill 2313 in 2013, a major transportation initiative passed with bipartisan support. Howell helped preserve several state parks through his passion and support of land conservation.

William Howell was elected to the board of directors of the Virginia War Memorial. Howell represented Virginia’s 28th District in the commonwealth’s House of Delegates for almost 30 years, from 1992 until 2018. He also served 15 years as speaker of the house — the second-longest serving speaker in state history. During his tenure, Howell played a critical role in the General Assembly’s strategic investment in education, economic development and mental health services. Of his many legislative achievements, one of his most notable was House Bill 2313 in 2013, a major transportation initiative passed with bipartisan support. Howell helped preserve several state parks through his passion and support of land conservation.