White households in the United States have 10 times as much wealth as their Black counterparts and seven times as much as Latino households — a pattern that holds true in Virginia. Students at the University of Virginia School of Law recently made significant contributions to a new report aimed at reducing the gap.

The report, created by the Commission to Examine Racial and Economic Inequity in Virginia Law, for which Professor Andrew Block served as vice chair, focuses on how Virginia policymakers can increase economic opportunity for people of color in the state. Published in January, “Identifying Virginia’s Racially Discriminatory Laws and Inequitable Economic Policies,” is the third report in a series by the commission and a predecessor commission, both of which were established via executive order by former Gov. Ralph Northam.

“Centuries of pervasive, and lawful, discrimination and racial segregation in Virginia — which only really officially ended in the 1960s — has left too many people of color, and Black Virginians in particular, stuck between a rock and a hard place,” Block said. “On the one hand, due to such historic factors as inferior schools, segregated and inferior housing, and accepted employment discrimination, they have not been able to accumulate wealth over generations in the same way that other people have. And on the other, because of this lack of resources, it is harder for Black people to secure financing for housing, or obtain capital to start new businesses to begin that wealth development that is so necessary for generational economic advancement.”

Block, who leads the State and Local Government Policy Clinic, harnessed the efforts of several clinic students, research assistants and volunteers in assembling the report’s contents.

Among the report’s recommendations are creating a system for paid family and medical leave in Virginia, enacting a state earned income tax credit, taking steps to mitigate foreclosure and the ill effects of debt collection, and improving access to financing for small businesses.

Virginia has the largest gap of any state between a full-time salary based on minimum wage and the federally identified minimum amount needed to support a family of four while not slipping into poverty.

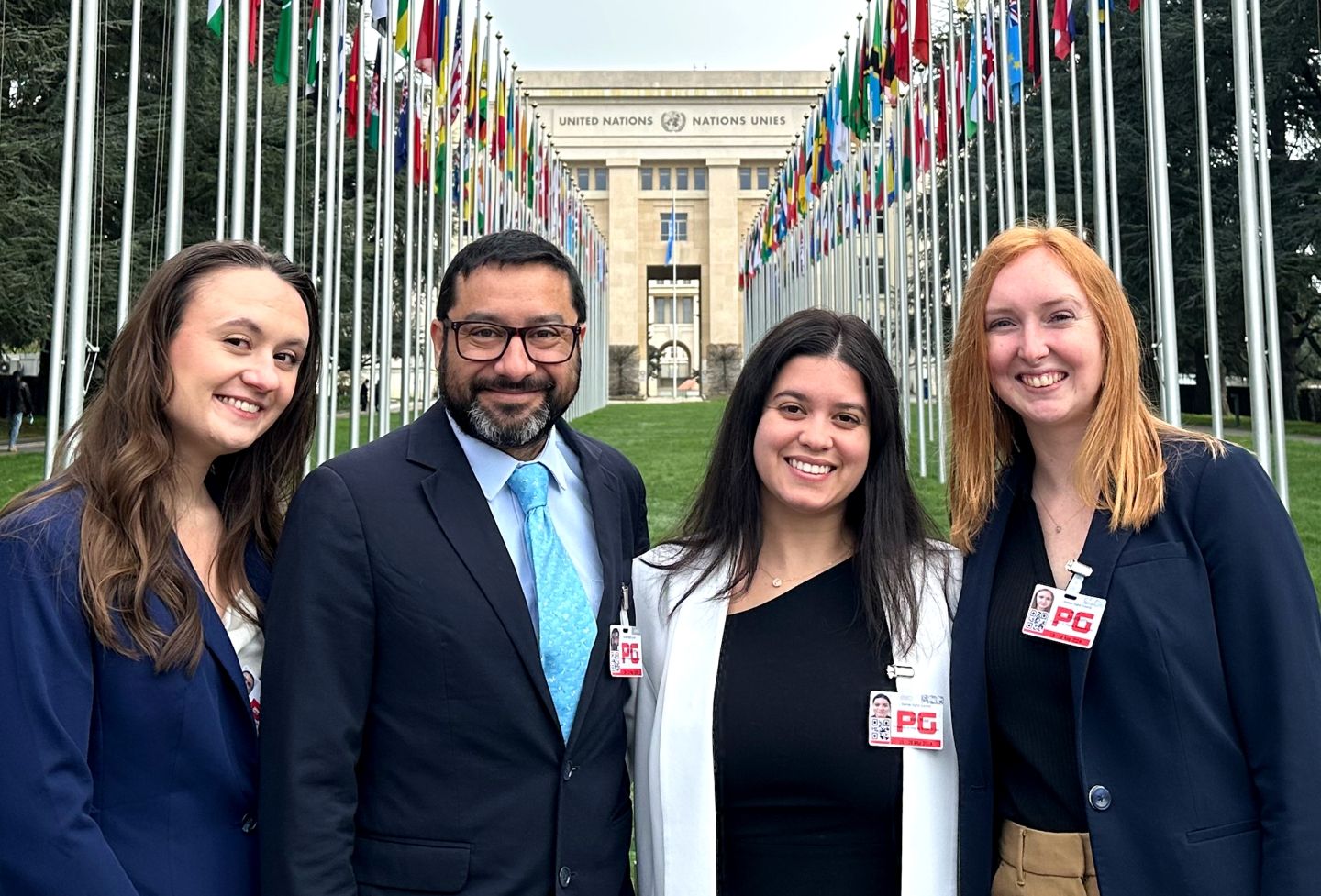

Second-year students Scott Chamberlain, Joe Aldridge and Julia Eger helped Professor Andrew Block research and write reports on how to reduce inequity in Virginia. Photo by Julia Davis

Second-year students Scott Chamberlain, Joe Aldridge and Julia Eger helped Professor Andrew Block research and write reports on how to reduce inequity in Virginia. Photo by Julia Davis

Block said the students were “critical” to the commission being able to both develop a robust set of policy proposals, and write and publish a report to make both the research and the recommendations available to the public. For each commission meeting, students would research the issue on the agenda and write a policy memo explaining various policy ideas from other states or that experts suggested. For the final report, the students synthesized all the research memos and policy ideas into a single narrative form. “They deserve a lot of the credit,” Block said.

Last summer, second-year student Joe Aldridge worked on the paid family and medical leave and rural issues sections of the report, as well as research on property taxes.

“Going into this project, I was already aware of the racial wealth gap and systemic racism,” Aldridge said. “But even with that as my baseline, some of the disparities were mind-boggling — like that Black mothers are three times more likely to die during childbirth than white mothers in Virginia. But a lot of what surprised me as a white student from out of state did not seem to surprise the nearly all-Black commission.”

Through the experience, Aldridge was able to speak firsthand with policy advocates as well as boots-on-the-ground health administrators in poor, rural counties.

“I am going to be much more prepared for policy conversations going forward,” he said.

Aldridge added that the recommendations could have a broad impact.

“Before California adopted a paid leave program, white mothers took an average of four weeks of maternity leave, and Black mothers took an average of one week,” he said. “After the implementation of paid leave, both groups take an average of seven weeks. Virginia could see results like that too.”

Second-year student Scott Chamberlain, who began working on the report as a research assistant to Block and continued while taking the clinic, said the proposals increase access to services and funding for all Virginians.

If the recommendations were implemented, for example, “all Virginians would now have notice of their ability to appeal a tax assessment, and any rural Virginian would benefit from initiatives like increased maternal health centers, broadband access, and improved educational infrastructure and resources.”

Through his research for the report, Chamberlain said he realized how integral many state agencies are in providing services to residents, and “how knowledgeable and passionate the civil servants who comprise those agencies are.”

“It was a real pleasure to be able to learn from and collaborate with people with decades of expertise and clear visions for what interventions would best address the inequities we identified,” he said.

Chamberlain added that he was surprised to learn that the state doesn’t mandate notice of right to appeal a property tax assessment, and that there are not statewide certification standards for tax assessors. He added that funds supporting broadband access and school infrastructure are “crucial.”

“The pandemic has highlighted and exacerbated the disparities in access to education between rural and urban, and white and Black communities,” he said.

Second-year student Julia Eger said she was taken aback at the extent to which racial disparities in economic opportunity are self-perpetuating.

“Because of the long history of racist policies in both Virginia and the United States as a whole, people of color often do not have the means to access opportunities such as buying a home or starting a business that would enable them to build wealth. This has resulted in multiple generations being trapped in a cycle of poverty.”

She said two critical recommendations are preventing debt buyers from bringing debt collection lawsuits after the statute of limitations has expired and enacting a truth-in-lending law to protect small businesses from predatory lenders.

“These issues stand out to me because the current lack of protections enables debt buyers and lenders to take advantage of people who do not have the means or the necessary information to protect themselves,” she said.

Eger said she learned how difficult, though rewarding, it was to find possible solutions to these longstanding, and harmful, racial disparities.

“Understanding the problem is one thing, but identifying which part of the government can mitigate the problem and how can be a much more complicated process,” she said.

Aldridge, Chamberlain and Eger were just three of the many law students who have supported the work of the two commissions over the last three years.

The commissions’ work shows that linking the past to the present through research and data can lead to productive solutions for addressing ongoing racial disparities, Block said.

“To really tackle the problem of structural racism that our history has created, we need to be intentional and fact-based in talking about the issues, and unafraid to put forward policy ideas that will help undo this harmful legacy.”

He added, “It is not a question of who is to blame today, it is a question of how can we continue to perfect our union, and build communities where everybody can thrive.”

The Law School’s Arthur J. Morris Law Library is working on a website that will feature the reports and their recommendations.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.