Change is the only constant, and it comes at us fast. Developments in information, science and technology open new possibilities every day — and add new questions for the law to answer.

The legal academy must be predictive to keep pace. UVA law faculty make it their business to identify the trends that will affect the law and our greater society, often many years into the future.

What does the future hold? Prepare to be astonished — or at least better informed — as the faculty bring you their latest predictions.

Driverless Cars / Warfare / The Stock Market / Tax Evasion / Forensics

Dispute Resolution / Health Care / Lawyering

1. Driverless Cars

In the future, whom do you sue if you’re injured by a driverless car?

Hint: It might not be human.

Professor Kenneth Abraham, one of the nation’s leading scholars and teachers in the fields of torts and insurance law, says plaintiffs in automated car accidents will sue the manufacturer in the years ahead.

Abraham has co-authored a paper with Stanford University law professor Robert L. Rabin that suggests a new legal framework for handling car accidents should no longer include the tort system or manufacturer liability for product defects.

“We think that once there is a critical mass of self-driving cars on the road, the manufacturer should automatically be liable for all injuries ‘arising out of’ the operation of the vehicle,” Abraham said.

The professors call their concept Manufacturer Enterprise Responsibility, or MER.

Under their proposed regime, automakers would pay into a fund with strict responsibility to compensate victims of bodily injuries, resulting in greater efficiency in delivering claims than today’s system, they contend.

Driver error, in theory, will no longer be a significant factor in accidents as highly automated vehicles become more reliable — so blame-shifting should become less relevant.

And according to rosier industry predictions, driverless cars are forecast to reduce the accident rate by as much as 80 percent.

“So this liability would not be a major burden on manufacturers,” Abraham said. “And they could pass the cost of MER on to customers in the form of a slightly higher purchase price.”

MER would include some exceptions to manufacturer responsibility, such as acts of terrorism. Futurists have loudly warned that vehicles governed by code and connected to the internet could be rife for hacking by terrorists.

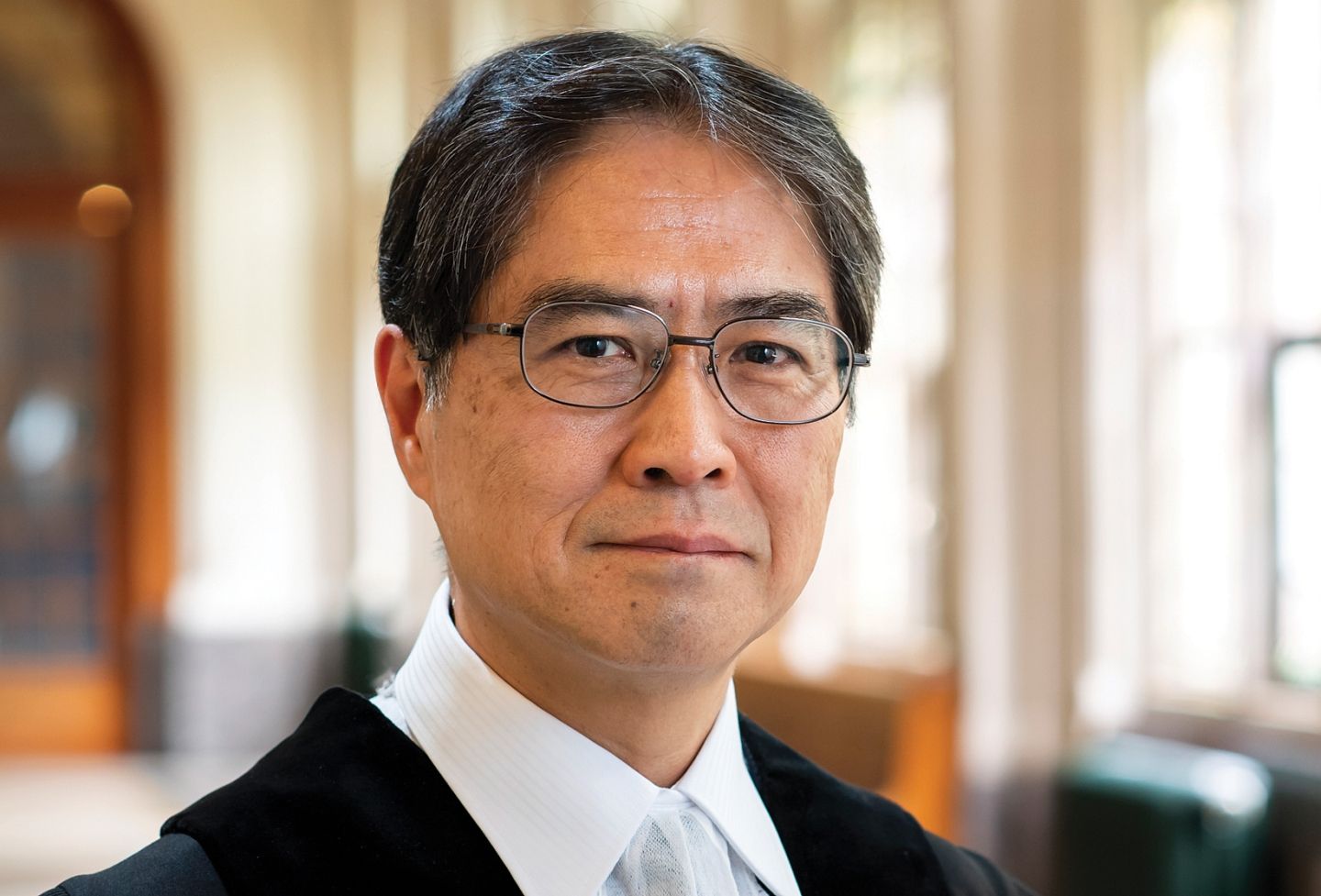

Kenneth S. Abraham is a David and Mary Harrison Distinguished Professor of Law.

2. Warfare

The military will increasingly use predictive algorithms to thwart attacks.

But can we trust this AI?

Police departments and the courts already use machine learning tools to help them understand criminal activity and assess risk. The military will increasingly apply the same types of technology to help prevent devastating terrorist attacks and to fight its armed conflicts, according to Professor Ashley Deeks, an expert on national security law who previously served in the State Department’s Office of the Legal Adviser and at the U.S. embassy in Baghdad.

Deeks looks at the potential downstream effects of the technology in her new paper, “Predicting Enemies.”

Machine learning models can filter through a seemingly endless supply of information about individuals, collected from a wide range of sources, including the technologies we interact with daily, to help make assessments about future behavior.

Who is communicating with whom? Where do they go and how often? Does the data indicate trends or unusual activity?

A subset of this technology, known as “deep learning” artificial intelligence, can detect patterns in vast amounts of data and, based on those patterns, predict the likelihood that a certain event—such as a roadside bomb attack — will occur.

Deeks said such technology could potentially result in assessments that are more sophisticated and accurate than a human analyst can perform.

But advanced AI might also lead the military to target or detain based on opaque reasoning that commanders may struggle to explain, she said. For the military, the obvious inclination would be to use the new tools under a veil of secrecy.

“Because military operations face fewer legal strictures and more limited oversight than criminal justice processes do, the military might expect — and hope — that its use of predictive algorithms will remain both unfettered and unseen,” she wrote.

Deeks said that would be a misguided policy.

The U.S. is said to have collectively detained at least 150,000 people in association with the Afghanistan and Iraq conflicts that followed the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks. The widespread detention of combatants during those conflicts led to the disclosure of numerous international law violations. Public backlash followed.

That kind of scandal could resurface, she said, if the military uses predictive algorithms to guide targeting or detention but remains secretive about the use.

But, she added, the quality of the data used to develop the algorithms, transparency in how the computer models make decisions and sufficient oversight mechanisms would be among ways that the military could garner public trust in the technology as it’s being implemented and refined.

Ashley Deeks is the E. James Kelly, Jr.–Class of 1965 Research Professor of Law and a senior fellow with the Center for National Security Law.

3. The Stock Market

Corporate shares could become traceable (again).

That means an asset could also become a liability.

Who owned your stock immediately before you? And before that? It might make sense to know — and for financial markets to track this history — for any number of reasons.

That was the case in the early 1900s, before the volume of trading got too unwieldy.

Professor George Geis, an expert in business law and corporate finance, argues in a new paper that traceable shares could return through the use of blockchain, the technology that underlies bitcoin. The cryptocurrency’s digital ledger is publicly available, providing an unambiguous history of ownership. The technology could be used to clear stock transactions in real time, transforming the current business model of clearance.

Such a change would lead to greater transparency and, perhaps, new legal responsibilities.

“I think the availability of traceable shares would allow us to begin to ask really interesting questions about the locus of corporate liability,” Geis said.

Among them: Would it be “buyer beware,” or could previous shareholders be sued for corporate misdeeds that arose during their ownership tenure?

Geis said the technology could also simplify the process of determining certain shareholder rights — including ones that don’t exist yet but could be added.

“It’s not inconceivable that we would see fragmented trading markets for stock,” Geis said. “If I want to [be eligible to] exercise a certain legal claim and only a subset of shares are going to qualify for that claim, I may call my broker and say, ‘I want to buy shares of a firm, but only shares that allow me to sue them for this Section 11 violation.’

“I think we may see trading markets become bifurcated or trifurcated.”

Geis noted that some countries are already launching pilot programs in this area and that some companies are already issuing securities that are connected to a distributed ledger.

George S. Geis is the William S. Potter Professor of Law and the Thomas F. Bergin Teaching Professor of Law.

4. Tax Evasion

Offshore accounts will become a thing of the past.

But will tax cheats find a new haven?

It’s becoming harder to hide money from the IRS in overseas banks, according to Professor Ruth Mason, an international tax expert whose amicus briefs have helped persuade the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the near future, it may be virtually impossible.

Following the most recent financial crisis, the United States passed a controversial piece of legislation known as FATCA: the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act. The 2010 law requires transparency by both foreign financial institutions and the U.S. citizens who collectively sock away billions in their vaults.

They must disclose the client’s name, address, account number, balance and more. Failure to comply can result in severe penalties for banks and taxpayers.

“The principal criticisms have been that FATCA is not only unilateral, but also extraterritorial,” Mason wrote in an article titled “Exporting FATCA,” co-authored with Joshua D. Blank in 2014. “Critics contend that FATCA requires financial institutions in jurisdictions outside the United States to act like ‘U.S. Treasury watchdogs’ and that it ‘strong arms every financial institution in the world into doing the job of the IRS.’”

The aggressive tactic, while unpopular, has worked. Blank and Mason predicted that criticism of FATCA from other countries would give way to emulation. In the years since the article, cooperation among countries through intergovernmental agreements has only grown, Mason said, and will continue.

“I think that my prediction with Josh Blank is basically coming true,” she said. “FATCA and similar transparency initiatives will lead to less tax evasion by individuals, though I temper that with all the question marks around bitcoin.”

Bitcoin investors, she said, are becoming notorious for either not reporting, or underreporting, income.

The extent to which the IRS steps up enforcement of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies may be the factor that determines their future as a replacement tax dodge.

Ruth Mason is the Class of 1957 Research Professor of Law.

5. Forensics

Questionable forensic assumptions will continue to be exposed.

Electronic evidence may fill the void.

As director of investigation for the Innocence Project at UVA Law, Professor Deirdre Enright ’92 reviews the latest scientific claims for and against the validity of methods of forensics used in prosecutions.

DNA evidence is considered to be highly accurate when assessing guilt in a courtroom.

So-called “junk science,” however, has led to the convictions of innocent people. Methods of hair, bite mark and fingerprint analysis are among the techniques that have been called into question.

The latest scientific assumption set to topple is shaken baby syndrome, Enright said.

For several decades, a community of medical experts has claimed that the presence of three symptoms in an infant — brain swelling, blood pooling in the two outermost meninges (layers that protect the brain) and bleeding behind the eyes — equate to iron-clad evidence of trauma. The injury would presumably come from a caregiver shaking or mishandling the child.

In recent years, however, defense lawyers have utilized scientific knowledge to push back.

“There are many conditions that cause the triad of symptoms,” Enright said. “You can have a cortical thrombose vein that is caused by dehydration and infection. Many doctors now would say you don’t get this from shaking.”

The Innocence Project recently represented a Northern Virginia woman who was convicted of shaking a baby at her home day care. She served prison time, despite no witnesses to the alleged abuse and no history of problems with her caregiving.

The woman won’t be able to challenge her conviction, however. The courts declined to revisit the case, and she was deported despite a request for pardon.

As the legal system understands more about physical forensic science, and where it’s fallible, electronic evidence may take on increased salience, according to Enright and others on the UVA Law faculty.

The devices that we use in our daily lives create virtual footprints. Metadata fills in the details.

“The question of when and whether the government can collect metadata on individuals is and will continue to be a pressing Fourth Amendment question,” said Professor Josh Bowers, an expert in criminal procedure.

But can electronic forensics be misinterpreted or misapplied as well? Enright foresees the possibility.

“Only ‘experts’ can analyze the hard drive of a computer and then testify about what is or isn’t on the hard drive, or when and how it got there,” Enright said. “Not many lawyers or judges share that expertise. We may be developing more junk science, and putting it in front of juries too soon.”

Regardless of the forensic technique, jurors may hold misconceptions that slow progress. A recent study by UVA Law professor Greg Mitchell and Duke Law professor Brandon Garrett found that jury-eligible adults still placed great weight on fingerprint evidence — even when compared to DNA evidence.

Deirdre Enright ’92 is director of investigation for the Innocence Project Clinic and professor of law, general faculty. Josh Bowers is professor of law. Greg Mitchell is the Joseph Weintraub–Bank of America Distinguished Professor of Law.

Should The Accused Be Free Before Trial?

When a judge considers bail for an accused person, she is assessing risk. Courts are increasingly using new machine-learning tools to help make decisions about pretrial release. But could the data contain biases against protected classes based on, say, ZIP code or other factors?

Professor John Monahan, an expert in risk assessment, is currently directing The Pretrial Risk Management Project for the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation. The project fosters dialogue among behavioral scientists, human rights lawyers and statisticians fluent in machine learning about what the technology gets right, and where it can possibly go wrong.

John Monahan is the John S. Shannon Distinguished Professor of Law; Professor of Psychology; and Professor of Psychiatry and Neurobehavioral Sciences.

6. Dispute Resolution

Showing up for court is so 2017.

It will become harder to form a class; arbitration will flourish.

Americans have already grown used to online dispute resolution to handle disagreements between buyers and sellers. A similar process may be coming soon to the courthouse nearest you.

Pilot ODR programs are currently being tested in county courts across the U.S.

Professor Michael Livermore, who studies where new technology intersects with the law, said companies like Modria, an ODR company led by the team that pioneered the technology’s use for eBay, are leading the push to expand into small claims, landlord and tenant disagreements, debt collection, civil contracts disputes and other matters.

Livermore believes these efforts could be transformative.

“Instead of going into court to resolve a dispute between two neighbors over a fence, is there a way to move that online to reduce the burdens of the court system, give people resolutions faster and do it in a low-cost way?” he said.

For larger matters affecting more plaintiffs, class actions have traditionally been the way to go. But forming a class in the future may be more of a challenge than in the past.

Increasingly, to do business of any kind, one must agree to arbitration in case of a dispute. That includes going to work. Earlier this year, the Law School’s Supreme Court Litigation Clinic lost Epic Systems Corp. v. Lewis in a 5-4 labor law decision. The court’s ruling effectively ended the right for employees to jointly pursue legal action (either through arbitration or the courts).

Employers, moving forward, may see little reason not to impose mandatory arbitration agreements.

“With the loss of Epic, the court has pretty much exhausted the arguments for avoiding arbitration,” said Professor Dan Ortiz, the clinic’s director. “I don’t see a lot more activity here — not because the court is not interested in the issue, but because there really isn’t much further it can go.”

Professor A. Benjamin Spencer, an expert in civil procedure, said the future of class actions of any kind hinges on the bar set by the federal courts, which have refined what qualifies in recent years.

“We could see fewer class actions in federal court and more forced arbitration if the court continues to move towards tightening class action standards and an ever-broadening interpretation of the Federal Arbitration Act that validates mandatory arbitration clauses in more contexts,” Spencer said.

Professor Jason Johnston, whose expertise is in law and economics, sees the apparent trend of using arbitration to avoid class actions, and potentially court, as a good thing.

“At least when it comes to consumer class actions, my research dealing with several years of class actions filed in the Northern District of Illinois shows that consumers get very little from the settlements of such class actions, and that such class actions have little deterrent effect.”

He added, “The most important trend in civil litigation over the past 10 to 15 years is the rise of the self-represented litigant. For these people, arbitration — which is cheap, informal and quick — is often the only viable means of real recovery.”

Michael Livermore is professor of law. Dan Ortiz is the Michael J. and Jane R. Horvitz Distinguished Professor of Law. A. Benjamin Spencer is the Justice Thurgood Marshall Distinguished Professor of Law. Jason Johnston is the Henry L. and Grace Doherty Charitable Foundation Professor of Law, Armistead M. Dobie Professor of Law, and director of the John M. Olin Program in Law and Economics.

7. Health Care

The doctor’s office may soon become the lawyer’s office, too.

Medical-legal partnerships are on the rise.

Why does the United States have statistically worse medical outcomes than other nations in the industrialized world? Part of the answer, according to Professor Dayna Bowen Matthew ’87, is that social conditions that impact health are not equal for everyone in the U.S.

“Although the equal protection clause forbids discrimination, state, local and federal governments regularly erect legal barriers that impede equal access to decent housing, employment, education, health care, pollution-free neighborhoods, access to justice and even food,” Matthew said. “These barriers disproportionately prevent disadvantaged communities from living healthy lives.”

Medical-legal partnerships are helping to change that.

MLPs are coordinated efforts between lawyers and the health care providers to enforce laws “that give everyone an equal opportunity to be healthy,” Matthew said.

Often embedded on-site, the lawyers aid physicians and their patients in legal matters that may influence the patients’ health — even more dramatically than medicine, genetic history or the patient’s own behaviors, she said. These attorneys may be challenging landlords who provide substandard living conditions one day, working on environmental policy proposals the next.

In a report last year for the Brookings Institute, where Matthew is a nonresident senior fellow, the health law expert explained that the partnerships save lives — and do so affordably.

“The model has demonstrated its potential to improve vulnerable populations’ health, at a reasonable cost, by improving the social conditions in which they work, play and live, but MLPs can reach only a small fraction of the populations that most benefit from their services, until they are sustainably financed,” Matthew wrote.

As of 2017, medical-legal partnerships could be found in 155 hospitals, 139 health centers and 34 health schools across the country.

Matthew co-founded the Colorado Health Equity Project, a medical-legal partnership incubator, in 2013. UVA has a medical-legal partnership as well.

With an aging population, and more awareness of how health disparities affect the poor, women and people of color, is this, then, a model for future growth?

Matthew said yes — but only if social awareness and social spending continue to rise to meet the challenge.

Dayna Bowen Matthew ’87 is the William L. Matheson and Robert M. Morgenthau Distinguished Professor of Law, the F. Palmer Weber Research Professor of Civil Liberties and Human Rights, and Professor of Public Health Sciences. She is the author of “Just Medicine: A Cure for Racial Inequality in American Health Care.”

8. Lawyering

Big data will transform the legal field.

What changes are ahead for lawyers and the legal academy?

Attorneys and law professors alike already rely on advanced data sets to form conclusions about information. Where will this lead?

Law firms of the future will more frequently review the text of past court decisions in an attempt to predict or sway future ones, according to Professor Michael Livermore, who researches court decision-making. Algorithms can reveal, for example, preferred wording that might appeal to a judge.

“The trick is big data. You have to have a lot of data,” Livermore said. “If you’re operating before a district court judge, you can potentially access every document that judge has ever produced and published, and you can apply text analysis tools to those documents.”

Courtroom advantage aside, he said, saving money for clients will be the main driver of change — with formulaic, high-volume legal work leading the way. The discovery process has already become highly automated.

“In large-scale litigation, it is not uncommon to have a mind-boggling number of documents to review,” Livermore said. “But whereas in the past an army of associates would be deployed for the task, new technologies can leverage the knowledge of a smaller number of lawyers who can essentially ‘train’ the machines to comb through the documents for them.”

At the Law School, Livermore and Professor Mila Versteeg are among those on the cutting edge of big-data legal analysis.

As a founder of empirical comparative constitutional law, Versteeg sorts through the world’s constitutions in order to spot trends. By coding 200 variables from the constitutions of 200 countries, she learned, for example, that fewer nations have been following the U.S. constitutional model, long assumed to be widely influential.

Versteeg won a 2017 Andrew Carnegie Fellowship to further her work on the intersection between constitutional law and rights enforcement.

“I’m doing research on the decline of democracies and whether constitutions can help,” Versteeg said. “That’s a topic everyone is interested in. Using data to study constitutions gives us a much better understanding of when they work and when they fail. These are very important questions, and I think you can a see a trend in the academy of trying to take on these questions with data, although the practice is still relatively new.”

Despite technology, Versteeg or an assistant must still hand-code her data. Does a constitution include language that, say, refers to health care as a fundamental right? Code “1” for “yes” or “0” for “no.”

For everyday practitioners and those who don’t “do” numbers, however, there will be a product. Livermore is teaching a course this fall to help law students get accustomed to some of the new analysis tools.

“There’s a legitimate fear that as these tools come to market, people are going to start using them without really understanding how they work,” he said. “We want to help students be better positioned to take advantage of these products.”

In the case of artificial intelligence products, whereas some might view the technology as potentially taking away jobs, Livermore sees them as just as likely to spur competition. The ability to customize a legal argument — at which human lawyers excel — might become even more valuable, he argued.

In other words, lawyering should remain a safe career choice.

“There’s going to continue to be a place for lawyers,” he said. “A robot is not going to go before the U.S. Supreme Court anytime soon and say, ‘May it please the court.’”

Michael Livermore is professor of law. Mila Versteeg is the Class of 1941 Research Professor of Law.

—With reporting by Mike Fox and Alec Sieber