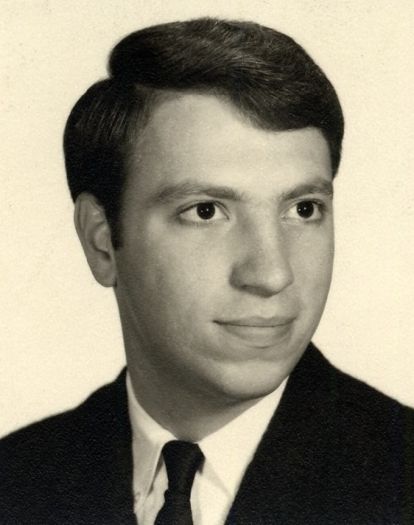

When Richard Bonnie graduated first in his 1969 class of the University of Virginia School of Law, the Vietnam War and the draft loomed over the lives of the graduating men. His own future seemed circumscribed by a pending military obligation. Never having taken an undergraduate psychology course, he certainly couldn’t have envisioned that he would later help define the intersection of mental health and criminal justice in the United States and elsewhere.

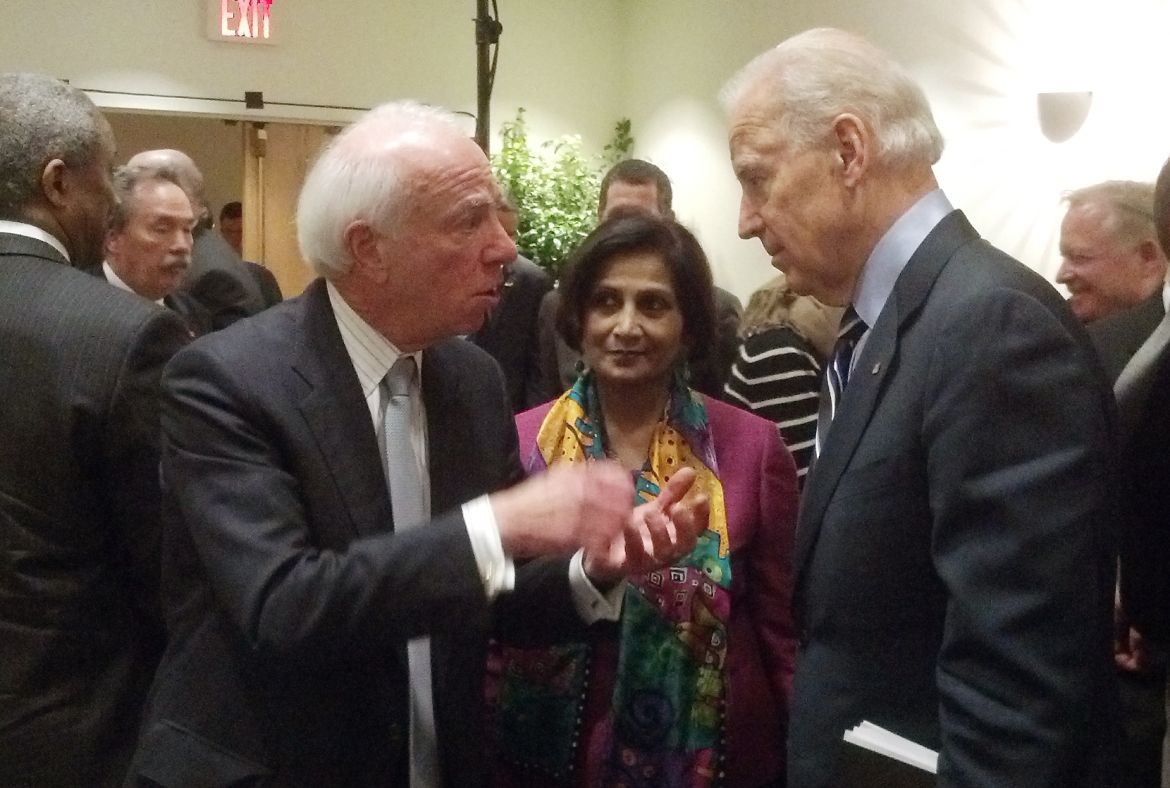

This fall, Bonnie stepped down from his tenured position at the Law School after nearly 51 years of teaching and research, 44 years of death row advocacy, and decades of shaping law and public policy on drugs, mental health, adolescent development and gun violence.

The Norfolk, Virginia, native first set foot in Clark Hall, the Law School’s former home, at a time when young people’s paths seemed defined more by catalytic and cataclysmic events than by personal agency.

Eight years earlier, the immorality of Virginia’s “massive resistance” to school desegregation pushed Bonnie — a liberal, Jewish youth — to choose to sit at the back of city buses and then nudged him north to Johns Hopkins University for college.

“I was thrust into the maelstrom of massive resistance at the very time that I was opening my eyes to the world around me and becoming conscious of my own identity — and of my responsibilities to others and to my community,” Bonnie wrote in a personal essay in “Law Touched Our Hearts,” a 2009 collection of essays he co-edited with UVA Law professor Mildred Robinson marking the 50th anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education.

His contemplation bred new ideas about the role of race in inequality and criminal justice, and “transformed” him from a kid who dreamed of playing professional baseball into a serious young student who knew he wanted to embrace the law as a path to reform.

Despite its Southern locale, he quite liked the vibe when he visited the Law School in the mid-1960s, and with the Vietnam War in full swing, it made sense to stay close to home for his legal education — but what kind of future lay ahead was unclear.

“It was the ’60s, and our nation seemed to be coping with a tragedy every moment,” Bonnie said. “And the Vietnam War and the draft narrowed your vision of your future.”

Because Bonnie had already received a draft deferment to attend law school, he knew he would be called up the moment he graduated unless he had a suitable military or qualifying public service commitment. During his second year, he accepted an offer from the Air Force General Counsel’s office at the Pentagon to serve in that civilian office for three years during his commitment as an Air Force captain.

Just days before Bonnie was set to graduate from the Law School, a possible clerkship with the Supreme Court evaporated and the school asked the 23-year-old Bonnie if he would instead like to teach for the year. The Air Force agreed to defer his active duty until July 1970.

During his yearlong teaching stint, Bonnie started a criminal appellate clinic that helped establish prisoners’ First Amendment rights and he began questioning the country’s drug laws, a path of inquiry that would seed virtually all his subsequent work.

The Marijuana Commission

Deep in the bowels of Clark Hall — two stories below the surface of the Lawn — Bonnie’s office shared a busy basement hallway with the Virginia Law Review managing board and a colorful young professor, Charles Whitebread, whom Bonnie dubbed the “pied piper for young ’60s counterculture students.”

The two were horrified by a Virginia court decision that sent a young man to prison for 20 years for possessing a small amount of marijuana.

“I’m sure Charlie smoked weed and other mind-altering substances, while I’m just a boring innocent who’s never touched the stuff,” Bonnie said. “But I didn’t think you should put people in jail for it.”

Together they wrote an influential Virginia Law Review article about the history of U.S. marijuana laws, based on case law, legislative background and a few newspapers. The article took over virtually the entire June 1970 issue.

Soon Bonnie had to leave to work at the Pentagon, where he focused primarily on freedom of speech in the military, along with negotiating communications infrastructure for new base agreements. He also drove back to Charlottesville to present Law School seminars on issues he was learning about in the military. On one of those trips, he attended a lunch event at the Judge Advocate General’s Legal Center and School, next door to the Law School, about the newly enacted U.S. drug laws and President Richard Nixon’s National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Abuse. The commission came to be known as the Shafer Commission, after former Pennsylvania Gov. Raymond P. Shafer, who served as chairman.

At the lunch, Bonnie sat next to the Department of Justice’s speaker, who had just been appointed executive director of the new commission.

“It came up that I had just written this article on the history of the marijuana laws, and he said, ‘Well, how would you like to be a consultant to the commission?’” Bonnie recalled. “I said, ‘I can do better than that! All you’ve got to do is get John Dean [his colleague in the Justice Department and then general counsel to Nixon] to tell the Air Force to send me over to the White House.’”

He spent the next two years as the associate director of the Shafer Commission.

“It was a life-changing event,” he said. The job informed his values, taught him how to lead multidisciplinary working groups and synthesize massive amounts of information and facilitate consensus on difficult policy issues.

Both Shafer and the vice chair, Harvard psychiatrist Dr. Dana Farnsworth, characterized Bonnie as a “principal architect” of the commission’s two reports, including its unexpected recommendation that simple possession of marijuana be “decriminalized.”

Bonnie and Whitebread’s historical research in the federal records also provided the material for their co-authored 1974 book, “The Marijuana Conviction,” which ties prohibition to xenophobic perceptions and argues for the decriminalization of marijuana possession. The book was republished in 1999 and is considered a drug policy classic.

“My work at the commission was essentially a graduate education in addiction, clinical psychology and social sciences,” Bonnie said. “Everything I have subsequently done in my career is essentially attributable to the serendipity of sitting next to the commission’s executive director at lunch. It introduced me to areas of law, science and public policy that I otherwise would not have known a thing about.”

A New Institute

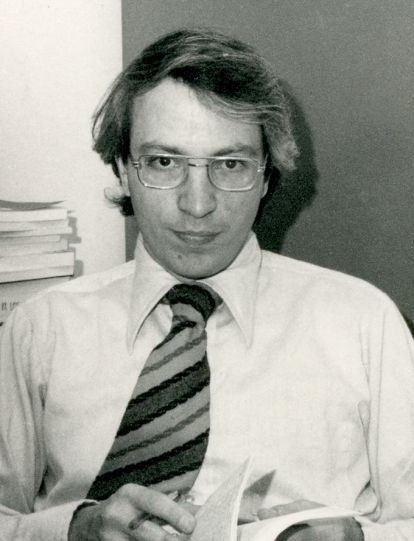

Bonnie returned to UVA Law in 1973 after three years in Washington and found an intellectual home in a new research center the Law School and Medical School were developing together.

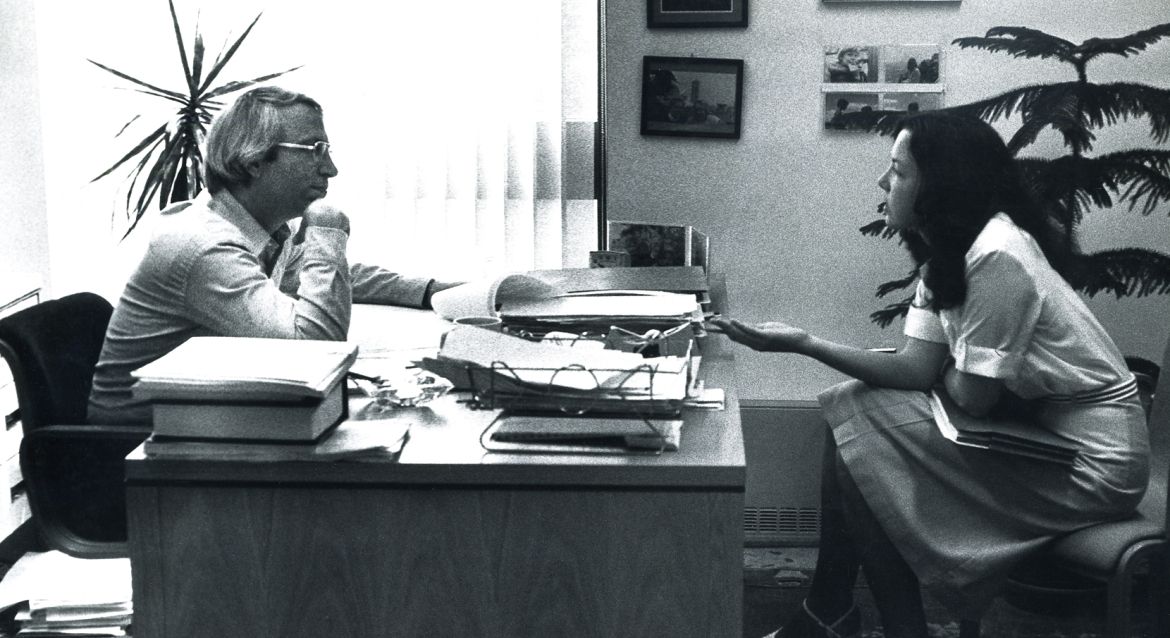

The center, which is now known as the Institute of Law, Psychiatry and Public Policy, was led by a psychiatrist named P. Browning Hoffman, who had been recruited from Yale and trained by thought leaders in the emerging medical ethics field.

“When I showed up, we created this new interdisciplinary program and were able to fund postgraduate fellowships, and many people who are now leaders in the field were trained here,” Bonnie said. “It was an opportunity to seed a new field, and was a genuinely exciting period of intellectual history.”

Perhaps the most important achievement of the new institute during the 1970s was a highly successful pilot project, funded by the commonwealth, demonstrating the feasibility of “de-institutionalizing” forensic assessments in criminal cases and conducting them in the community by trained psychiatrists or psychologists. This was a model for the nation, as was the statute — drafted by Bonnie — setting out the rules and procedures governing these assessments.

Hoffman died unexpectedly in 1979 but left a nationally influential forensic clinic as his legacy. The Law and Medical Schools have continued to collaborate and have sustained the interdisciplinary bonds in law and medicine that Bonnie and Hoffman created.

Over the years, the institute would expand research and legal innovation in law and psychology in several ways, including reformulating criteria for involuntary psychiatric commitment, promoting advance directives for people with mental illness, refining the boundaries of the insanity defense, advocating for “red flag” laws to limit gun purchases by persons at elevated risk for suicide or violence, pushing to raise the legal age for purchasing for tobacco and alcohol, reducing the use of criminal punishment as a deterrent to the use of other addictive drugs, and rethinking the rules governing competency to stand trial.

In 1980, Bonnie helped recruit John Monahan, a trained psychologist specializing in public policy and the psychology of violence, to continue and enrich the interdisciplinary research between the Law School and the institute.

Noting that Bonnie is among the handful of scholars at the forefront of analyzing laws regulating both mental illness and substance abuse, Monahan said “it’s hard to exaggerate Richard Bonnie’s accomplishments.” Monahan also called Bonnie “the hardest-working person I’ve ever known.”

While Bonnie intends to keep working — now from Slaughter Hall as the Harrison Foundation Professor of Medicine and Law Emeritus — his interests have shifted.

“Now that I’m retired, I’m really focused on trying to make sure that all this intellectual investment and financial investment that’s been made here — and the program Browning and I developed — survives and thrives in the decades ahead,” Bonnie said.

Touching History

Bonnie’s expertise at the intersection of psychiatry and criminal law has drawn him into the legal aftermath of some of the most notable crimes in recent history, from the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan; the Unabomber homicides, 9/11 and D.C. sniper attacks; and the Virginia Tech and Sandy Hook shootings.

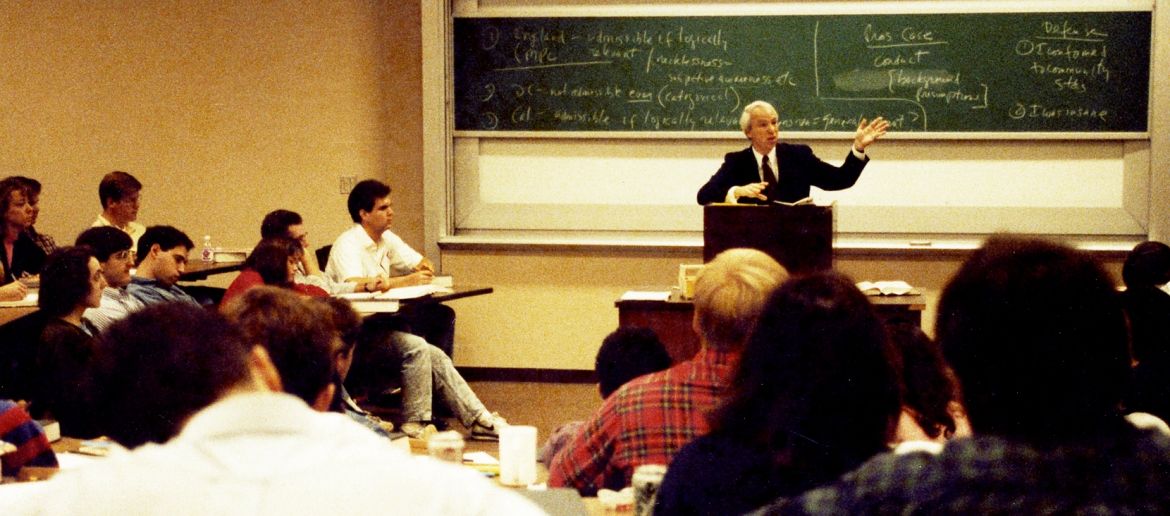

Professors Peter W. Low ’63 and John C. Jeffries Jr. ’73 drafted Bonnie to co-author a casebook on criminal law because of his expertise in applying mental health issues, Low said, particularly to the analysis of the insanity defense and capital punishment. The three also co-wrote “The Trial of John W. Hinckley, Jr.: A Case Study in the Insanity Defense.”

Low calls Bonnie’s work on the Hinckley book “innovative, effective and important” to understanding the complexities of the defense. After Hinckley was acquitted — by reason of insanity — of attempting to assassinate Reagan (and wounding three others), the defense was nearly abolished at the federal level and in some states. Instead, Bonnie developed a “mend it, don’t end it” strategy and convinced the American Bar Association and American Psychiatric Association to endorse his proposed modifications to the defense — focusing on the defendant’s appreciation of wrongness rather than their volitional control — and the abolitionist zeal wore off. In 1984, Congress adopted his compromise for the federal insanity defense criteria.

Robinson, with whom Bonnie edited the collection of essays by a generation of lawyers who grew up in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, struck up a close friendship with Bonnie when she joined the Law School in 1984, later becoming the first tenured Black female professor.

“Over the years we found commonality in our shared — though obviously different — background as Southerners who were both Brown babies,” Robinson said. “I always remember Richard speaking of how the Brown decision animated our project as being ‘in service of the constitutional imperative to form a more perfect union.’ I believe these words have been my dear friend’s polestar throughout his life and work.”

Robinson said Bonnie worked assiduously to improve the medical and legal professions’ understanding of “those who struggle with life circumstances — drug usage in its many guises, personal abuse, mental illness — that undermine, curtail and potentially defeat any possibility of living fully into productive lives.”

Like Robinson, Low also admires Bonnie’s work ethic, calling him “tenacious and thorough” and “indefatigable,” all qualities that came into play when he was pulled into death penalty defense work due to being one of the few scholars to have written on capital punishment and mental health.

He co-represented the first cluster of prisoners sentenced to death under Virginia’s revamped 1976 capital punishment statute and spent the next decade of his scholarly career writing about capital sentencing, with a particular focus on the ethical dilemmas arising in capital defense. Several of the clients were also examined by the forensic psychiatry clinic attached to the institute he and Hoffman had helped build.

“If you’re going to do a post-conviction appeal, you have to find a lawyer to do it, and there wasn’t a capital representation system around then,” Bonnie said. “Who the hell do you send people to? Because I had expressed interest in this, people just said, ‘Go call Bonnie.’”

One potential client, however, contacted him by mail. The return address said the letter was from Theodore Kaczynski, a man also known as the Unabomber. Kaczynski, a former mathematics professor, attacked other academics, businessmen and random civilians with homemade mail bombs between 1978 and 1995.

Though the letter was sent in the winter of 1998 from Kaczynski’s underground supermax prison cell in Florence, Colorado, Bonnie wasn’t keen to open it.

He took the letter to class and one of his students opened it there.

It did not contain explosives, but it had a bit of a bombshell request: Kaczynski wanted Bonnie to write a petition to vacate the guilty plea that had kept him off death row. He had pleaded guilty in part to avoid pleading insanity, but Kaczynski would rather risk capital punishment or life in prison than have his mental capacity questioned, Bonnie said. Kaczynski also wanted to maintain his right to appeal his conviction based on illegitimately admitted evidence.

Bonnie wanted nothing to do with overturning the life sentence meted out to a man who had killed and maimed academics like himself. Nor did he want to expose Kaczynski (or anyone else) to the death penalty by retracting his guilty plea. On the other hand, Bonnie believed strongly in the right of psychologically competent defendants to make decisions about their own defense.

“I believe in the autonomy of defendants to make their own decisions, just like people in the medical context make their own decisions,” Bonnie said. “The doctor doesn’t make the decision — the patient makes the decision — as long as he is competent to do so.”

In January 1999, he and a student flew out to Colorado to meet Kaczynski in person to assess his mental state. Bonnie decided to take the case.

“He’s got his issues, but I didn’t think it was really interfering with his ability to make a rational decision about this,” Bonnie said.

Bonnie was able to launch an ethics seminar that very semester, in which the class would discuss the dilemmas raised by the Unabomber’s case and help draft his habeas petition. As the months passed, though, Bonnie decided he couldn’t file the petition.

“Let me just say, I didn’t come to this lightly. Obviously, I had made a promise to him but ultimately it just took me a while — working with psychiatrists and his previous counsel — to understand how disturbed he really was, and that he wasn’t making a rational decision,” Bonnie said. “But I also had an ethical problem because he only had a certain number of days until the District Court’s deadline.”

As a compromise, Bonnie gave Kaczynski the draft petition, which was nearly complete. Kaczynski finished it himself, filed it, and lost at the district and circuit court levels. Thus he remained sentenced to life under the guilty plea, though he did convince one circuit court judge of his position on appeal. (While serving his life sentence, Kaczynski killed himself this past June in a North Carolina medical facility for federal inmates.)

Other thorny ethical issues arose over the years. From 2002-06, Bonnie advised the court-appointed lawyers representing Zacarias Moussaoui, the would-be 20th hijacker in the 9/11 attacks.

“They had their hands full, to say the least,” Bonnie said.

After Moussaoui pleaded guilty over their objection in 2006, the jury could not agree on whether he should receive a death sentence. Just days later, Moussaoui sought to withdraw his guilty plea, eventually appealing up to the Fourth Circuit. The clerk’s office then asked Bonnie to represent him, but he declined to take the case on the grounds that Moussaoui’s most likely motivation was to mock the U.S. legal system. (Moussaoui remains in prison under a life sentence.)

Virginia, which once led the nation in executions, abolished the death penalty in 2021, after 113 people had been executed under the 1976 statute. Although Bonnie applauds the repeal, he takes no credit for the policy achievement.

“[A]s it is administered in the United States in the twenty-first century, capital punishment is an ignoble activity, not a praiseworthy one,” Bonnie writes in a forthcoming essay in a book examining the death penalty. “Its human subjects are an unfortunate collection of disadvantaged, deprived, and defeated criminal defendants selected by a discriminatory lottery. How can this be done in the name of justice? In OUR name?”

Shaping Public Policy

Bonnie’s indefatigable work ethic led to another achievement that looms large in his career. He was elected to the National Academy of Medicine in 1991 and subsequently led committees of experts charged with writing its reports on more than 10 public health challenges, including two reports on tobacco, and others on underage drinking, aging, adolescence, juvenile justice and the opioid crisis.

He was also tenacious about using his influence and connections in the field to create opportunities for colleagues and students — often without ever mentioning his behind-the-scenes efforts to the beneficiary. When Professor Margaret Foster Riley developed an interest in health law and bioethics after her husband died of cancer, Bonnie recommended her for three different academy report committees, including the National Academy of Sciences’ 453-page strategy for reducing the over-prescription and misuse of opioids.

“Richard does that for anyone working with him, at least where he thinks they can do more than they’re doing and that other entities could benefit from their help,” Riley said. “And it’s not just for me — I could tell you at least 10 people he’s done this with, maybe more.”

When Katharine Janes ’21 applied to the Law School to pursue juvenile justice, her essay mentioned that she hoped to one day work with Richard Bonnie. He never knew that, but he invited her to be his research assistant after she took his 1L Criminal Law class. Janes eventually served as the team leader of six RAs working with Bonnie on delinquency adjudication and criminal prosecution of juveniles, contributing to his work as a reporter for the American Law Institute’s Restatement on Children and the Law.

After Janes told Bonnie of her interest in pursuing academia, he gave her the opportunity to co-author a paper he was writing and provided “invaluable guidance” on her independent research. He also authored such an effusive letter of recommendation for her that one employer asked in jest just how much she had paid Bonnie to write it.

“My career as a student and lawyer would not be what it is without Professor Bonnie,” Janes said. “He took such care to cultivate me to be the type of scholar and intellectual I wanted to be, in the field that I wanted to be in. His support was unconditional and so genuine, and I will be forever grateful.”

For the 34 years he has been associated with the National Academies, Bonnie has been a force driving policy change, Riley said.

“This almost never happens, but the Food and Drug Administration has either met or is striving to meet almost all the recommendations of his [opioid] committee,” Riley said. “By being such an important voice in the National Academies, in many ways he has focused and guided many of the issues that the institution has focused on over decades.”

Bonnie is demure about such lofty praise. “I’m good at organizing other people to write reports, I guess, so the academies just kept asking me to do those things,” he said. “As I see it, my story is more about the culture of the times and about the Law School than it is about me. I’m just a basically boring person, who is interested in learning about challenging problems and coming up with reasonable solutions.”

The challenge — and the opportunity — is to formulate a framework that exposes the choices that have to be made, he said. That was true with marijuana in 1973 and is true with deciding how to deal with youth offenders in 2024.

In 2007, Bonnie was awarded the University’s 54th Thomas Jefferson Award, the University’s highest honor, given annually to a University community member who exemplifies in character, work and influence the principles and ideals of Jefferson. In presenting the award to Bonnie, then-President John T. Casteen III read from a citation that said, “The world’s foremost legal expert in the field of mental health law, Mr. Bonnie has fundamentally shaped the way in which doctors, lawyers and citizens approach their relationship with some of the most vulnerable members of our society.”

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.